Courtesy of: Greisa Martinez, Selena Herrera, Debbie Chen, Hector Rivera Suarez, Press On, and DeMarcus Akeen Suggs

Courtesy of: Greisa Martinez, Selena Herrera, Debbie Chen, Hector Rivera Suarez, Press On, and DeMarcus Akeen SuggsFeatured Leaders

The South is the fulcrum of the United States. Its legacy of movements for justice—from abolition to the civil rights movement of the 1960s—is alive through a new guard fighting today’s battles against injustice. These activists have not necessarily been seen as leaders, either because they are young, working on causes that have not received due attention, or using unconventional methods, like the arts. But to spur change across the country, it is imperative to support these social justice organizations and leaders, whose success in the South can influence movements across the entire country.

These leaders are unafraid to use their voices and their collective power to fight for change. Often, they are youth, women, queer, BIPOC, or hold identities that intersect with several of these. As marginalized people denied power, they have borne the weight of injustice and systemic oppression in the US. But that has only fueled their fire; they are clear-eyed about how to build a path toward equity.

Right now, in the US, the South is at an inflection point. Widespread issues—from attacks on voting rights, to widening socioeconomic and geographic divides, to a rise in hate crimes—are intensifying in the South. The region is diversifying rapidly, and the rights of marginalized communities are at stake amid the waves of change.

This piece is part of our featured series, The Story of the South is the Story of America.

This year, we doubled our support across the region as part of Ford’s historic social bond, bringing our total giving in the South to $175 million since 2016. We spoke with leaders from six organizations we support across the South. For all of them, the South is a complicated place. It’s a site of injustice, but also of potential. A place of struggle and of hope. It’s where they’ve been told, time and again, that they are outsiders—but it’s also home.

Each of the leaders are working toward their own goals: protections for undocumented immigrants, greater investment in youth of color, justice and representation for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI). But they know, too, that their aims and hopes are intertwined: resisting any form of injustice means resisting them all. The organizers are committed to working across lines of race, class, and geography to build a more just South—for their communities now, and for future generations that will continue to shape the region.

Greisa Martinez: United We Dream

Martinez, 33, is the executive director of United We Dream, an immigrant, youth-led network that fights for justice, dignity, and rights for all immigrants. UWD is supported by the Ford Foundation.

Grounded in a movement

I am undocumented, unafraid, queer, and unashamed. No matter what anyone else says, I am here to stay. I’ve truly been transformed by the immigrant rights movement: It’s where I came out as queer, and learned that all of my identities can be celebrated and cherished. My parents are part of the catalyst for my organizing. I am committed to fighting so they can have a peaceful life, earn a living wage, access health care, and feel safe when they go off to work.

Shepherding solidarity

The core of United We Dream is this idea that people most directly impacted by injustice in this country are also the closest to the solutions. I think that’s especially true with young people—we are bearing the brunt of decisions made decades ago. When I think about what UWD has done to defend DACA or how the Sunrise Movement has mobilized youth, it’s young people marching, rallying and building power together.

Courtesy of Greisa Martinez

Courtesy of Greisa MartinezGreisa Martinez runs the youth-powered United We Dream, which fights for justice for immigrant rights. The organization’s “special sauce” is bringing “someone from a place of hopelessness to hope, from isolation to community.”

The special sauce for UWD is when we can bring someone from a place of hopelessness to hope, from isolation to community. When people connect with others who resonate with their same challenges, we as a community can create systemic change.

Strength from shared experience

My father was a Southern Baptist preacher, but on the side he worked as a carpenter to make money. He would repair and resell wooden pallets we found as a family at factories and industrial sites. One night, we were out looking for pallets, playing music, and this older white man came barreling out of the factory toward us. I still remember the look in his eyes: the disgust and anger and rage. He yelled at my parents, saying they should be ashamed, that we shouldn’t be there. But we weren’t doing anything illegal: We were just trying to survive.

Every Black and brown person has felt eyes like that on them. The immigrant justice movement is part of a larger racial justice movement in the country—especially in the South. In Georgia, undocumented people like me face barriers in attending public universities, and our rights are constantly under threat. Our work is to try to do what my parents did that night, which is to say: We are not defined by what people say about us; we are proud and no one is allowed to treat us that way.

A “discipline of hope”

This country was founded on the extraction of labor and the taking away of self-determination from Indigenous folks, from Black folks. That pervades everything, especially in the South. But we are grounded in a discipline of hope that things can change. When I see the uprisings for Black lives, for immigrant justice, my heart hurts, because we have to fight. Fight against the forced sterilization of undocumented women in ICE and Customs and Border Protection detention centers and fight for Black people not to be killed by police. But this tension is a sign of life. All of these young people—from Black women to Indigenous folks to Latina women—are relentless in the pursuit of saying ‘Enough.’

Hector Rivera Suarez, Siembra NC

Rivera Suarez, 24, is an organizer with Siembra NC, a grassroots organization in North Carolina defending undocumented and Latine communities from injustice across the state. Hector uses the term Latine, a gender-neutral term for Latin people, similar to Latinx.

Finding identity, finding community

I identify as a gay, undocumented and Latine immigrant from Mexico; my parents brought my sister and me here when I was eight years old. It took me a while to understand the intersectionality of all of those identities within myself, but they’ve now become part of the foundation of how I organize for my community.

Fighting for justice and liberation is not something that we do just for our community. We can’t have liberation for undocumented folks while our Black, trans and queer families are still being discriminated against. It’s important to remember when we’re fighting, we’re fighting together for everyone.

Organizing through understanding

The questions we ask ourselves constantly as we organize are: What are the biggest challenges facing our community? What can we do? We have a campaign at Siembra now called 10K Latinos Dijeron—which translates to 10K Latinos Said—and the goal is to survey 10,000 Latinos on various political issues, and understand how they feel about them and how they’re affected by them. We’ve heard that people want driver’s licenses so they can feel safe going to work and taking their kids to school; that people are being taken advantage of by their employers because they think they’ll be afraid to take action.

Courtesy of Hector Rivera Suarez

Courtesy of Hector Rivera SuarezAs an organizer in North Carolina with Siembra NC, Hector Rivera Suarez works to build power for marginalized communities and defend their rights.

Showing solidarity against injustice

What we’re showing as Siembra and as a community is that we aren’t afraid to take action. This spring, a TikTok went viral of an IHOP worker in Winston-Salem, North Carolina sharing how she was not getting paid her full wages because she was undocumented. People in the community reached out to Siembra, asking if we could support, and we helped organize workers to walk out and put pressure on the manager to pay the full wages—not just for this one worker but for all of them.

When others can see people winning, they see that it’s possible for them, too. We’ve had so many more people reach out with similar issues who are now motivated to fight. When people reach out to us and want to organize, it’s important that we start by sharing our wins and showing the power of working as a collective and what we can accomplish together. And then we move onto know-your-rights workshops. A lot of times, people will not know that, as undocumented people, they have rights and can use the legal process to gain protections.

The power of many

The South is filled with untapped potential. As time passes, the Latine population will grow to a point where our presence, over multiple generations, will create change. My vision for the future of the South, for North Carolina is to mobilize our entire community to have the capacity to knock on every eligible Latine voter’s door. I want to see the people who make decisions for our community start to take us seriously, and for us to gain power so we are the ones making the decisions.

Selena Herrera

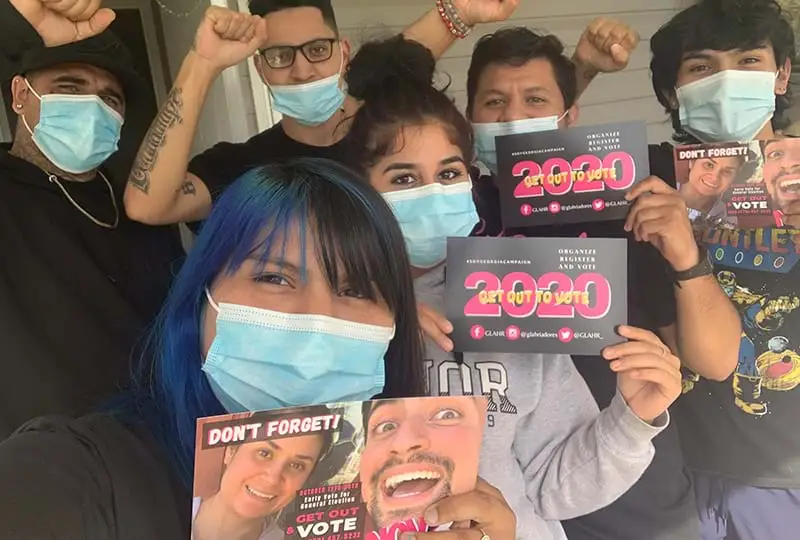

Selena Herrera, Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights

Herrera, 22, is the south Georgia youth organizer with Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR), which organizes Latino communities across the state to defend their human rights, resist unjust legislation, and mobilize for civic engagement.

Breaking the chain

I was born and raised in Tifton, Georgia. My family migrated here for agricultural work; I worked in the fields and packing sheds. My parents would tell me they came here so I could have other opportunities. But there were—and still are—so few programs for Latino youth in the South.

As a child, I skipped school and ran the streets. Because of that, I was incarcerated at 13 in a youth detention center in Macon. I encountered so many people who didn’t believe in me. The correctional officers would tell me, “I’ll see you next time.” Because in their mind I was part of a pattern, and when that’s all people see in you that’s what you start to believe about yourself.

I realized I didn’t want that for myself or my siblings. I wanted to break the chain. And now, I’m the mother of three kids, and they’re growing up in the same community. They’re my biggest motivation—I want to fight for their opportunities, rights and dignity, along with my own.

Finding a home in the movement

GLAHR’s been around since 2001; I joined as an organizer last October. At first I was a bit intimidated because I was new to it, but I’ve been welcomed with open arms and lifted up with opportunities to lead. Early on, I was the outreach coordinator for southern Georgia and led a team of 25 young people, and I came away from that feeling even more empowered. GLAHR recognizes that it’s so important to empower youth and support the next generation of leaders, because we’re who will keep the fight going.

Courtesy of Selena Herrer

Courtesy of Selena HerrerSelena Herrera led efforts to mobilize Latino voters in south Georgia, part of her work as a youth organizer with Latino Alliance for Human Rights.

The power of resistance

It’s so important to work as a coalition with our Black and brown communities to resist disinvestment and disenfranchisement in our communities: The fact is that rural communities are often forgotten about or overlooked. We focus on encouraging people to see that voting is one of our main strategies to fight for our rights as a community and a coalition. It takes work to figure out new strategies to get rid of the barriers to justice, but that just gives us more motivation to keep fighting.

Building the foundation for a different future

Investing in youth—that’s the start of change for the South. This year, GLAHR created a Latino youth initiative called The Block. The kickoff, a two-day event I helped organize, was in my hometown. We wanted to create a space for young people to begin their political awakening—to learn about the history of GLAHR, the power of organizing through mobilizing and how that leads to change. We talked through different bills and policies and how they affect our communities. It was amazing to see all of our youth completely focused, taking it all in. We plan on taking this across the state and organizing these events for youth in different cities and towns, who will form The Block together.

Debbie Chen: OCA Greater Houston

Chen, 50, is the civic engagement programs Director at OCA-Greater Houston, an organization established in 1979 to advance the social, economic, and political wellbeing of AAPI people in the Houston Area. OCA-Greater Houston is part of the AAPI Civic Engagement Fund, which is supported by the Ford Foundation and was founded in 2014 to build power across AAPI-led organizations.

In solidarity, building visibility

Growing up Chinese American in the South, I had moments when I was bullied, but I remember my parents saying to me that no matter what, I have to keep my head down and ignore it. But when I started organizing with the AAPI community, I realized that it doesn’t have to be that way—we have power when we work together.

But even in organizing, our attitude was often, “Let’s get it done and not draw attention to ourselves.” The rise of hate crimes since COVID-19 toward Asian Americans has been a wake-up call. We can’t be silent about the microaggressions we’ve felt all along, the fact that our people are not represented in the history books—these perpetuate this notion that we’re foreigners here.

To end this cycle of stigma, it’s time to be more vocal as a community. Now, there’s been a shift: Our community has pulled together to act in a more unified manner, to be visible, and to assert that we belong here like everyone else. During COVID, we ran a full-page ad in the Houston Chronicle publicizing our shared efforts to donate meals and personal protective equipment to frontline workers and calling for unity against hate.

Courtesy of Debbie Chen

Courtesy of Debbie ChenThe rise in hate crimes against the AAPI community pushed Debbie Chen and fellow activists with OCA-Greater Houston to be more vocal about the bigotry that faced by their community, and build bridges with other marginalized communities.

Building a bigger pie

In Houston, the Latinx community is quickly becoming the majority community. The AAPI community is committed to sitting at the same table and working together to move everyone forward. Marginalized communities are moving away from this scarcity model, where the pie is only so big and we have to fight over the remaining slices. We have to support each other and work in solidarity across race and class lines. Then we can build a bigger pie.

This shapes our approach to youth advocacy and community organizing. For example, we’ve partnered with Mi Familia Vota to create and foster a civic engagement club, where AAPI and Latinx students collaborate on business plans in response to community needs. Whether they go on to run for office, become an organizer or a business leader, I hope they see everyone—across race and class and status—as a peer. And, during our census outreach, we worked to reach the Asian residents in areas with some of the lowest census response rates. These neighborhoods also have a lot of African immigrants, low-income folks, and Latinx people. Our thought was: Why not leave resources at every door? We are all in this community together.

Rewriting history—and the future

A lot of the challenges we face as an Asian American community stem from what people learn—and don’t learn—about us. Every year, we have a fresh crop of students who have been indoctrinated to see a version of America that doesn’t reflect the history of our community and of so many others.

We are in this moment of opportunity and momentum where people are willing to work in coalition and call for change. We have to start now and continue to build our power.

DeMarcus Akeem Suggs, Alternate ROOTS

Akeem Suggs, 35, is the resource synergist and development director (or what he refers to as resident hype man) for Alternate ROOTS (Regional Organizations of Theaters South), an arts organization that focuses on dismantling all forms of oppression.

Connecting through the arts

I am a Black, gay, Christian man, and a product of the Great Migration. I grew up in Minneapolis but have returned to Memphis, where my maternal grandmother was from, so it feels like coming full circle.

I began my career as a dancer with the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company, which is rooted in the Black experience. I thought I was going to be there forever, but I didn’t have a lot of say in terms of policy, such as how artists were compensated. So I got more involved in the community and in administration, and that’s when it all hit home for me—through the administrative work of connecting to artists, learning their needs, and advocating for them, I was able to use my skills to push our systems to allow artists to have power and agency in their work.

Art as an agent of change

The arts are central to transforming culture, and there is no culture without the creative expression of its people. What we do at Alternate ROOTS is support the magic of individual expression and how it relates to broader collective transformation.

At ROOTS, we’re in constant conversation with our members about everything from how the organization is run to how the staff operates to how we stay true to our mission of eliminating oppression in the field. Our staff are artists as well as members, and we see all of our members as our board of directors.

We’re unique in that we grant to individual artists, not just arts organizations, through a simple application process that removes barriers to access. We want to support artists at any level, in any community, to do their work. But we operate as a membership-driven organization because it’s through connection and community that the movement can strengthen and grow. It’s an environment where we’re always trying to figure out how we can move forward as an organization and keep pushing for change in the culture.

Melisa Cardona

Melisa CardonaAlternate ROOTS uses the arts to dismantle all forms of oppression. DeMarcus Akeem Suggs, development director, was a dancer who moved into activism when he saw the potential of the arts to be a force for justice.

A practice grounded in place

The hallmark of the artists we work with is that their practice converges at their craft, their community, and activism. Nationwide, folks are paying attention to artists whose work is highlighting social inequities and working to dismantle oppressive systems. But that’s always been our way of existing. At ROOTS, we’re not limited in our definition of art—it can look like a storytelling gathering led by Indigenous people, or like the Tiny is Powerful movement in Charleston, North Carolina that was launched by a coalition of ROOTers to support small businesses. How do we create spaces for people and communities who have been habitually disinvested to feel like their voices count? Through the arts.

The South as a site of change

Culturally, the South is often dismissed as the birthplace of bad things in this country. But what I’ve noticed is the South is also the birthplace of movements that challenge systems—from holding the country accountable to equity and democracy to amplifying the beauty of Black culture and how it has influenced the DNA of the whole country. There’s a movement among Southern artists to drive both representation and policy change through their work. I think of the choreographer Julie B. Johnson. She has developed a series of participatory workshops that employ movement and video to share stories of the historical injustice of women of color incarcerated in Georgia, and to amplify the need for action.

Art in the South embodies the experience of connecting, person to person, and forming resilience in the face of disinvestment. There is so much promise here because of all the work that’s happening to shift the culture and the policies, and the art retains this essence that people are at the heart of it.

Manolia Charlotin and Lewis Wallace, Press On

Charlotin and Wallace are part of a group of co-founders of Press On, a Southern media collective that catalyzes change and advances justice through the practice of movement journalism.

Owning our story

We in the South who experience systemic oppression have lived under repressive regimes: we know how to fight them, change them, and survive and tell our stories in spite of them.

But too often, Southern stories of oppression and resistance are told by journalists and documentarians who are not from or connected to communities seeking justice. These parachute journalists, outsiders who come in to report stories for a day or a week, often misunderstand and misrepresent the roots of our people, region and movements.

In 2019, we founded Press On with a group of journalists and activists either based in the South or deeply connected to Southern movement-building and liberation work: Anna Simonton, Mia Henry, Chelsea Fuller, JoEllen Kaiser and us. By funding and supporting movement journalists, Press On is elevating underrepresented stories, diversifying journalism and carrying social justice forward.

The power of movement journalism

Movement journalism is anchored by a set of commitments: To center the voices and experiences of systematically oppressed people, to amplify the work of social movements, and to expose and investigate root causes of oppression.

Movement journalists work in service to justice and liberation by fostering collaboration between journalists and grassroots change-makers, and supporting stories created by marginalized people. They cover stories that matter aligned with movements for change. They range from renowned leaders like the pioneering Ida B. Wells, to the many documenters of the Black Lives Matter movement, to the family photographers and oral historians who have saved the stories of Civil Rights and Black liberation movements by passing them down through the generations.

Our inaugural Southern Movement Media Fund gave money directly to 18 movement journalism organizations and individuals in the South to support their work.

Matt McClain/The Washington Post

Matt McClain/The Washington PostIda B. Wells, a pioneer of movement and investigative journalism who became a voice of justice for Black America, is honored in Washington, DC’s Union Station.

Amplifying every voice

Press On is a response to gaps and inequities in funding and infrastructure that have existed since the foundation of the United States. We are building power among journalists and organizers already activating change in their communities to reinvent those systems.

Our grantee, the National Council of Elders, is creating an oral history and podcast project archiving elders’ historic contributions to social justice movements. The council was founded by key figures across some of America’s most iconic social justice movements like the Rev. James Lawson and Ms. Dolores Huerta. The council’s mission is to work in solidarity with young activists to solve problems in the present, understand their analyses of contemporary struggles, and share elder knowledge and historical perspective. Our hope is that this project will create an important historical document as well as a key piece of movement media.