An Ode to Love

Love is profoundly political. Our deepest revolution will come when we understand this truth …

The transformative power of love is the foundation of all meaningful social change …

When all else has fallen away, love sustains.

~ bell hooks, Salvation: Black People and Love

Radical Love offers a joyous vision of love’s transformative power and calls for a return to love. While we may know about love, many of us have forgotten what love is or why we need love to sustain life. This exhibition is inspired by love as a transformative force and begins by thinking of love as an action rather than a feeling; love assumes responsibility and accountability. What is urgent about the politics of love in our present moment is that we are claiming a space within culture, with no sense of fear or apology, for society’s others. The enveloping red walls of the gallery allow us to literally and metaphorically recalibrate the space and create a positively exhilarating center for otherness and action.

The future is dark—Is this the darkness of the tomb, or

the darkness of the womb? Is our nation dead or still

waiting to be born? We choose to believe that our nation

is in Transition. We are in labor. Labor requires pain—

and love. Revolutionary Love is the call of our times.

~ Valarie Kaur, civil rights activist and founder of the Revolutionary Love Project

The clarion call to revolution rings clearly through time. Mary Thomas was one of three women who led a violent rebellion against the Danish colonizers in the West Indies in 1878. Belle and Ehlers’s sculpture immortalizes her as a queen of the Caribbean. She is seated on a humble throne, her feet resting on a plinth of coral stones, an early building material in the colonial towns of St. Croix. In her right hand she holds a sharp sugar knife and in her left, a burning torch. Her face is calm and loving, but her arms are raised and poised for action.

Omar Victor Diop reinterprets defining moments of black protest in his photographic series Liberty (Universal Chronology of Black Protest, 2016). He portrays a group of young rural women who represent the thousands of Igbo women who marched together to protest the Warrant Chiefs, whom they accused of restricting the role of women in government and the economy. Many of these chiefs were forced to resign, courts were attacked and destroyed, and the British imposed reforms.

Lina Iris Viktor’s richly gilded red, blue, and gold painting, Eleventh, merges abstraction and figuration alongside motifs drawn from West African textiles, classical mythology, and contemporary art. She foregrounds the perspective of the “Libyan Sibyl,” an ancient prophetess of fate and foresight drawn from the Greek pantheon and so named because of her fabled connection to North Africa. Viktor, in the role of prophetess, foretells the intrusion of Western social and political systems into Liberia, a long-forgotten paradise with direct links to the United States. It is an ambivalent and conflicted place, but one where the national motto, adopted in 1847, remains “The love of liberty brought us here.”

The issue is not freeing ourselves from representations.

It’s really about being enlightened witnesses when we

watch representations.

~ bell hooks, Cultural Criticism and Transformation

Being an enlightened witness means becoming critically vigilant about the world we live in and the power of representation. The portraits in McCallum and Tarry’s Evidence of Things Not Seen pay homage to the actions of 104 participants in the 1956 Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama. The work’s impact comes from its use of classical portraiture to subvert the way photography is often used selectively, as “evidence” of guilt, and to bestow new honor and dignity on the protesters, individually and collectively. Evidence makes space for revolutionary love.

Ebony G. Patterson’s opulent installations reveal untold stories of Jamaica. While the landscape of Jamaica is as idyllic as a postcard, all is not well in … she saw things she shouldn’t have … for those who bear/bare witness, 2018, an intricate jacquard-woven tapestry that portrays a grim story: Concealed within the colorful trim, embellishments, fabrics, glitter, beads, gold objects, brooches, ribbons, and floral wallpaper are black body parts, hands, and feet, in unnatural positions. Their presence in the artwork is an act of protest and our presence before it, an act of witnessing. How do we see and what are we willing to bear?

Baseera Khan’s Seats, rendered in various degrees of abstraction, are intended as oblique portrait of new members of the 116th House of Representatives and acknowledges the women who redefined political representation. Khan’s strategic use of beauty conceals the tensions inherent in what it means to be native, female, Muslim, and American.

An enlightened witness par excellence, Faith Ringgold creates incredibly human representations of African American individuals, histories, and themes that have been excluded from representation within the American cultural canon. Though the sculptures are actually “soft,” the issues she addressed in these works continue to bring hard truths about African American and female experience into public consciousness. As Evelyn, 1978, Suzanne, 1977, and Yvonne, 1978, gaze out at us from their plinth in the exhibition, they continue to bear witness to concerns that are as relevant today as they were over 40 years ago. Artists have the power to create new representations, document realities, and alter perceptions.

The acceptance of our present condition is the only

form of extremism which discredits us before our children.

~ Lorraine Hansberry, To be Young, Gifted and Black

In our present condition, thousands of immigrant children have been separated from their parents, after crossing the southern border of the United States, as part of the new immigration strategy by the Trump administration.

Recovering the power of a mother’s love, Vanessa German’s and Rose B. Simpson’s unusual sculptures speak to the sacred bond between a mother and child. In German’s depiction, a woman holds a black porcelain child in her outstretched arms; glass jewels stream from her eyes like tears. But the mother is enrobed in white, representing the presence of light, purity, innocence, honesty. Simpson’s mother carries her child on her hip; both gaze directly at us. She is a warrior and a protector. With a metal crown atop her head and a metal square at her feet, she stands between stories of the creation of the world and the origins of her people. We are that, multiplied.

Nep Sidhu’s magnificent Confirmation B represents the artist’s search for confirmation of his idea, image, and sense of his mother, who has passed. Through architecture, calligraphy, and adornment, he uncovers new ways of seeing and feeling that transcend time and space, engendering endless parallels and possibilities for keeping the primordial bond alive. Raúl de Nieves explores the complex facets of motherhood through the prism of sculpture. His Fina works offer beautiful and dramatic depictions of his mother, whom he credits with bringing his family to the US and raising him as a single parent following the death of his father when de Nieves was a boy. de Nieves says his work is both a tribute to his father and a promise for a “better tomorrow” (artnet, March 2019).

Can we accept our present condition? Surely, it forces us into a confrontation with ourselves and our children that demands a reevaluation of what truth means.

You have to act as if it were possible to radically

transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.

~ Angela Davis, from a talk at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

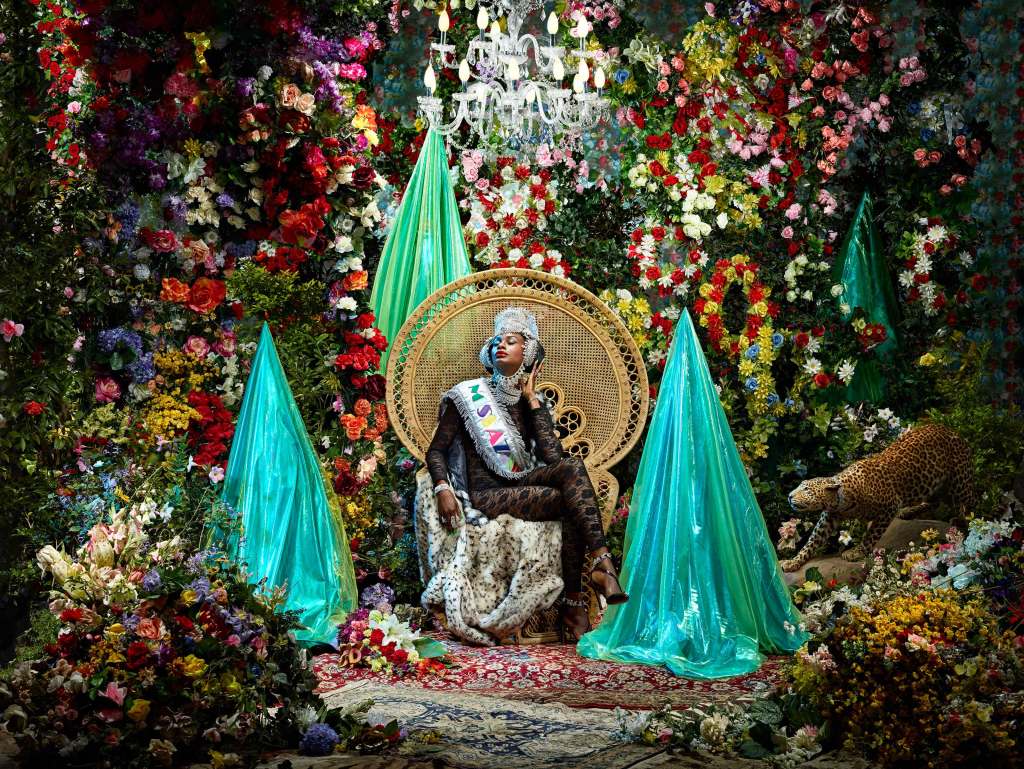

Loving otherness offers us a way to reconnect with selfhood, to uncover the essential goodness of being human, and allows everyone to find themselves and glory in loving one another. Athi-Patra Ruga responds to a vision of post-apartheid South Africa as a “Rainbow Nation”—one that in reality forgot and rejected many marginalized people. His opulent and self-assured Umesiyakazi in Waiting reclaims a space for queerness. Rashaad Newsome’s collaged paintings activate queer black bodies to produce dissenting forms of beauty and desire. The poses of the figures in his work interrupts processes of normalization and small gestures challenge the status quo.

Similarly, in his collage Find Your Gaggle, Jody Paulsen asserts the importance of camaraderie and of friends who support and provide a sense of belonging to queer folks as they navigate the difficulties of family and society. Jah Grey transforms common notions of black masculinity, offering black men a way to reconnect with selfhood by uncovering the essential goodness and beauty of maleness, and allowing everyone to find glory in loving manhood. Sue Austin’s epic underwater achievement brings profound joy. Her art and advocacy radically transform the lives of disabled and nondisabled people alike.

We can love ourselves by loving the earth.

~ Wangari Maathai, Replenishing the Earth: Spiritual Values for Healing Ourselves and the World

If, as Angela Davis says, “radical” simply means grasping things at the root on a foundational and fundamental level, then surely Lina Puerta’s installation points to ancient knowledge that understands the roots of our pain and lovelessness as beginning with the land. Her Botánico-inspired installation is positioned between a lush atrium garden, the flourishing and decaying botanical motifs found in different artworks, and the modernist architecture of the Ford Foundation building. Puerta’s richly layered fragments of a landscape, where natural and human-made systems collide, sprout from exuberant red walls.

When I speak of love, I am not speaking of some sentimental and weak response. I am speaking of that force which all the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. Love is somehow the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality. This Hindu-Moslem-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief about ultimate reality is beautifully summed up in the first epistle of Saint John: “Let us love one another, for love is God and everyone that loveth is both of God and knoweth God.”

~ Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., Strength to Love

We must “learn to read,” says Thania Petersen, and to interpret the world in a more beneficent and inclusive manner or risk aberrant readings that lead to religious dogma. Her work mourns the loss of divine love and argues for its return. Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt weaves his liberation theology and aesthetics of radiant glory through his opulent altarpiece. He invites us to kneel before the altar of human love and compassion. In the atrium garden, Imani Uzuri takes us on a quest through the vast cultural galaxy, dreams of freedom, visionary resistance, self-determination, spirituality, and imagination, a place where we can love one another.

Love takes off masks that we fear we cannot

live without and know we cannot live within. I

use the word “love” here not merely in the

personal sense but as a state of being, or a

state of grace -not in the infantile American

sense of being made happy but in the tough and

universal sense of quest and daring and growth.

~ James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

Maria Berrio’s collage returns us to the mother as the bestower of blessings; grace is the love that protects, gives courage, and is the birthright of every child.

We yearn to end lovelessness, to live in a culture where love can flourish, and to create a world where everyone knows love. To heal our wounded communities, according to bell hooks, we must return to love, because to give ourselves love and to love others is to restore the true meaning of freedom, hope, and possibility in all our lives.

Love is our hope and our salvation.

– Natasha Becker

Ford Foundation Gallery

320 E 43rd St, New York, NY 10017

Visitor info

Curated by Jaishri Abichandani and Natasha Becker