In a criminal justice system that’s astonishingly expensive and disproportionately punitive and yet stunningly ineffective at rehabilitating inmates or preventing crime, the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI)—a program of Bard College in Rhinebeck, New York—stands out for an approach that’s both innovative and practical. Founded in 1999 by then-student Max Kenner, BPI creates an opportunity for incarcerated men and women to earn a Bard College degree while serving their sentences.

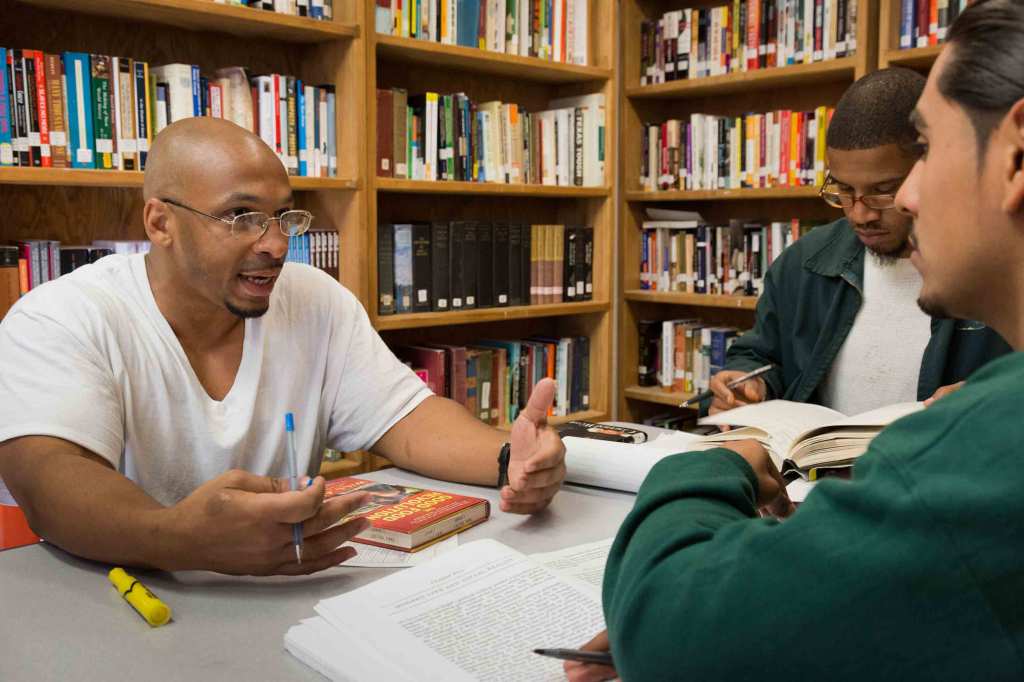

BPI currently enrolls almost 275 incarcerated men and women, from six medium- and maximum-security prisons across New York State. Most of these students are people of color who come from the state’s poorest urban communities. Higher education transforms their daily realities and offers a renewed sense of possibility—and not coincidentally, reduces recidivism dramatically.

The foundation supports BPI under our Higher Education for Social Justice initiative, one of our efforts to provide opportunity for society’s most marginalized. The organization was a featured success story in last month’s launch of My Brother’s Keeper, a White House initiative that aims to empower boys and young men of color, in which Ford is a partner.

Kenner, now BPI’s executive director, spoke to us about the power of education and the importance of recognizing accomplishment where we least expect it.

You started the Bard Prison Initiative when you were an undergraduate. What made you understand the urgency of prison education at that point in your life?

My interest in college in prison, and the origins of BPI itself, followed from a recognition of two separate but concurrent crises: One was that so many young people—young men of color mostly, from New York City—were winding up in prison, radically constricting their options for the future and limiting our potential as a society. At the same time I was recognizing the power that a liberal arts college can have in changing people’s lives and making them more effective members of a democratic society—and feeling real frustration with how difficult it was for different kinds of people to get there.

Why is prison education so important?

A vast body of knowledge from across the political spectrum has revealed that nothing we do in criminal justice does more to reduce violence within the correctional institution than college in prison programs. Nothing better prepares people in prison to be parents to their children and be ready for work post-release. Nothing is more effective in ensuring that they don’t come back to prison. And nothing is more cost-effective.

We’ve managed to make Bard a place that includes incarcerated people not as subjects of some kind of charity, but as students who are judged with the same courtesy and generosity, and with the same level of expectations and rigor as other students on campus. The hard work of these students has not only changed their behavior, but made them role models for the many hundreds of other men or women in those same correctional institutions.

BPI aims to address deficiencies in mainstream education as well as criminal justice—not usually areas that are understood in tandem. How does that work?

In higher education across the country, we’ve gotten used to assuming that certain types of people won’t succeed. Our country’s investment in prisons, along with its divestment in higher education, speaks to a collective cynicism about young people: that we can’t assume they will be curious or successful or virtuous. And that has become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Frankly, Bard College is not in the business of crime prevention. But we are in the market for fabulous students, and our business is trying to convey to students of as many types as possible, from as many places as possible, that the arts, the natural sciences, the humanities really matter and can impact their lives for the better. The more people who are engaged with those kinds of things, the better off we all are.

In February, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced ambitious plans to fund college classes in 10 state prisons. What will it take for prison education programs to get more public support and investment?

I think the patience in the United States for spending endless amount of money on keeping people in prison—institutions that deliver so little for us—is coming to an end. It’s a fact that we have invested huge amounts of resources in a system that induces hopelessness and begets more and more violence.

There is no evidence that prisons release people who are going to be less likely to be dependent on the state for healthcare, housing, education, employment, and welfare. There’s no evidence that it makes them less likely to commit crime. I think Andrew Cuomo’s willingness to stick his neck out and be bold provides some cover for elected officials and leaders in education across the country. But it takes courage.

How has the BPI program impacted the lives of its students?

Post-release, our alumni are busy achieving extraordinary and wonderful things. Some are managing businesses, pursing advanced degrees, cultivating careers for themselves in the arts. Most work in human services: with youth at risk, with the homeless, with other people who are coming home from prison and have less support than they did, with people who have HIV and AIDS.

Our alumni—who themselves are a network of self-supporting, self-sustaining graduates, so to speak, of the prison system—serve in New York City’s poorest communities as a cadre of examples not only of the terrible consequences of crime and punishment, but of the meaningful rewards of hard work and engagement through education.

What would the next generation of success look like for BPI?

What we have to work toward isn’t fixating only on the prisons, but addressing what we can achieve in education if we have a little courage. In every stage of life, we have to reach students earlier, and we have to not give up on students who aren’t convinced by education at age 17. We need as many outlets as we can to reach these students.

If we think of college in prison as a way to reduce recidivism, and we reduce the prison population and then throw in the towel, we have failed. If we think of college in prison as a way of convincing educators to do things differently and to take different kinds of students much more seriously, then we’re on the right track.