In the two years since the Ford Foundation identified inequality as the central focus of all our grantmaking, I have been asked countless times, “What does this mean for the foundation’s support for human rights work?”

The question can be answered in very straightforward terms: We will continue to be a major funder in this field, supporting human rights actors and practices within all our efforts to overcome inequality. Let me say quite clearly, however, that this does not mean business as usual for us. Rather, it represents a more complex mix of continuity and disruption.

There is general agreement that, over the past several decades, the movement helped establish a moral consensus around human rights across the globe; created international mechanisms to protect these rights; spurred the adoption of national legal standards around human rights; and eventually grew from a fairly narrow movement focused on physical integrity to one addressing almost every aspect of social, economic, cultural, and political life—and in doing so, has secured a framework and an approach that has been embraced by a broad array of other movements, focused on everything from indigenous peoples to Internet freedom.

And, from across the decades, there is also ample evidence that this human rights framework has been effective in confronting authoritarian regimes and, more broadly, in addressing violations related to political systems that persecute or discriminate against specific groups.

But we can also generally agree that its success in responding to human rights violations that have at their core unfair or biased socioeconomic systems has been much more limited. This is not an observation that hinges on a distinction between civil and political rights, on the one hand, and economic, social, and cultural rights, on the other. It is, fundamentally, an observation that suggests there is a common set of structural causes underlying human rights violations of all types—and that the movement has not yet brought its strength to bear on these underlying structural issues.

Harnessing a familiar framework in fresh ways

Here’s what I mean: If you live in Brazil today your chances of being tortured for (strictly) political reasons are fairly limited. However, if you are black and poor your chances of being abused or killed by local or federal security forces are basically the same as 50 years ago.

This is not a new challenge, or a new conversation, for the human rights movement. For at least 20 years now, one of the key questions we’ve been debating is whether the human rights framework of the past 50 years can now be harnessed in new ways—ways that were not foreseen at its origins but that nonetheless suit the framework and fit our times.

Our response at the Ford Foundation has been, and continues to be, an unequivocal yes. Given its legacy, it is clear to us that this remarkable framework can—and, I would argue, should—be applied to confronting inequality at its roots.

So, if the Ford Foundation is to address inequality, not just as an economic problem, but as a structural problem that also implicates social, cultural, and political systems, it is incumbent upon us to think about our human rights work in a different way.

But the question remains: Different how?

Making human rights real

One important difference between addressing human rights violations that derive from flawed political systems, versus human rights violations based on socioeconomic patterns, is that setting human rights standards is much more effective in addressing the former than the latter. Human rights standards, as a moral barrier to authoritarianism, may be extremely effective in the battleground of ideas. But those same standards are not that effective when there is a need to disentangle a complex system of socioeconomic norms and practices.

This is the challenge we talk about when we talk about “making human rights real”—the need to go beyond standard-setting to actual enforcement and implementation. This is the frontier that, for many years now, the human rights movement has looked out upon and made important forays into, yet has not succeeded in crossing.

There are many reasons why the movement has struggled to convincingly enter this terrain, but there is general agreement around one: Making human rights real for the vast majority of the world’s people requires the movement to go beyond reporting abuses, developing norms, and litigating cases—and to engage in more comprehensive and collaborative work with non-human rights sectors. The foundation has been supporting these efforts for many years, and we now have a number of solid cases demonstrating that when human rights initiatives are put to work in alliance with other actors and social movements, the results are very promising.

This is not just about new tactical alliances, but a more in-depth form of collaboration that responds to the need to bring diverse knowledge and activism together in a way that is, to some extent, extraordinary. But given the times we live in, and its unprecedented challenges—from the digital revolution to a global order in distress—this new form of collaboration between the human rights movements and other spheres of action is essential.

At Ford, this is what we think of as integration: a commitment to making human rights a key part of all our work, not an isolated component but a deliberate and integral approach within how we pursue broader goals.

An integral, collaborative approach

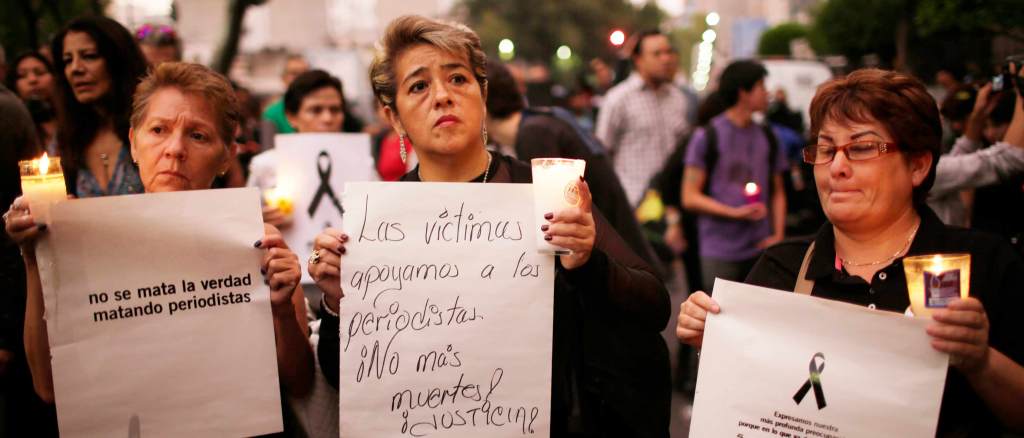

There are already some very powerful examples of this kind of integration among our partners and within the foundation. Our incipient work around criminalization is a case in point. We have defined this work as confronting a global trend to use the criminal system not as the last resort but rather as a first response. Societies across the globe are using the criminal system to contest values (persecuting LGBT people, criminalizing sexual and reproductive rights), to control specific groups (over policing minorities), to protect private or corporate interests (criminalization of indigenous leaders in Latin America), and to suppress dissident voices (closing civic space).

Looking at criminalization as an intersectional issue touching on many parts of our work, we have asked our team working on gender, racial, and ethnic justice to focus on criminalization when it harms people on the basis of their identity; our team working on civic engagement and government takes the lead when the focus is how criminalization limits civic engagement or trust in government; and our Internet freedom team addresses the role of new technologies in the global trend toward criminalization.

This is just one example. Our work around natural resources and climate change has a strong focus on human rights, the same way that we aim to ensure that our work on inclusive economies continues our efforts around business and human rights. Our Mexico office is putting human rights at the very center of its work around impunity, while in other regions we are looking at more specific actors (extractive industries) or rights issues (housing).

In fact, a recent report by the International Human Rights Funders Group found that in the year 2013, $270 million of Ford’s annual grantmaking could be categorized as addressing human rights in one fashion or another. Of this total, no more than $15 million represented grants made by our Global Human Rights portfolio. This reflects our long-standing belief and practice that rights are central to all that we do.

Integration as a new international standard

If this is a conversation that has been going on with our key partners and within Ford for a few years, in recent months there has been a renewed urgency to question if, instead of integrating human rights, we should actually go “back to the basics” and support international human rights bodies and institutions in a global context that is increasingly challenging.

There is no easy answer to this question. But if this context teaches us anything, it is that if human rights are going to continue being a key part of our global culture, today more than ever we need to make them a local reality. Integration needs to be the new international standard.

I said the question of how human rights work is to be funded in our quest to address inequality is not a simple one. It is complex work. But our overall approach going forward is, as I have also said, quite straightforward: Human rights funding will continue to be a priority. Our decision not to have a freestanding program focusing on the international human rights systems—as we have for the past 30 years at least—does not mean our funding is shifting away from this critical work.

As we confront inequality, we are working to redesign how we work to ensure that the successful human rights framework is harnessed to address the political and socioeconomic systems that reinforce inequality. We believe human rights can and should be a powerful contributor to these efforts, not as a stand-alone sector but as an integrated part of a 21st-century movement to achieve the promise of human dignity.