Franklin Thomas was a giant—an American original; a singular leader; an iconic figure in the history of the Ford Foundation and philanthropy, our city and all cities, our nation and the world. And just as Frank shaped a half century of human progress in our neighborhoods and around the globe, he shaped the course of my life, as a mentor, counselor, and friend.

I first met Frank many years ago in Harlem when I, a fledgling nonprofit executive at Abyssinian, hoped to emulate his astounding work with the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, the granddaddy of community development corporations.

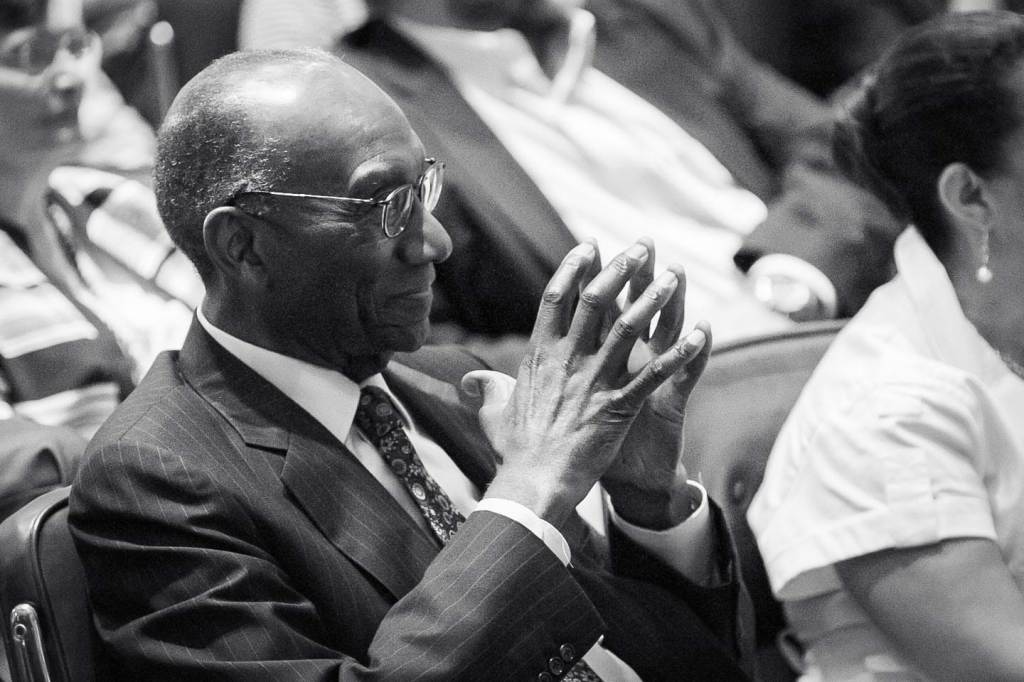

Franklin Thomas, right, joins Darren Walker, left, at the Ford Foundation. Thomas, who sat at the helm of Ford from 1979 to 1996, was a mentor, friend and counselor to Walker and many throughout the foundation.

To me, Frank was the consummate New Yorker. The son of immigrants from Barbados and Antigua, he made a life in Bed-Stuy and never left it behind. But he was also the quintessential leader of a new school of urbanism—a philosophy of revitalization that put people and communities at the center.

This philosophy found expression in the many institutions that Frank served and strengthened—at the agency that later became the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, the New York City Police Department, and, of course, in Brooklyn, where Frank’s profound legacy endures street by street, block by block.

Thomas, center, talks to residents of the New York neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, where he grew up with his immigrant parents after moving from Barbados and Antigua.

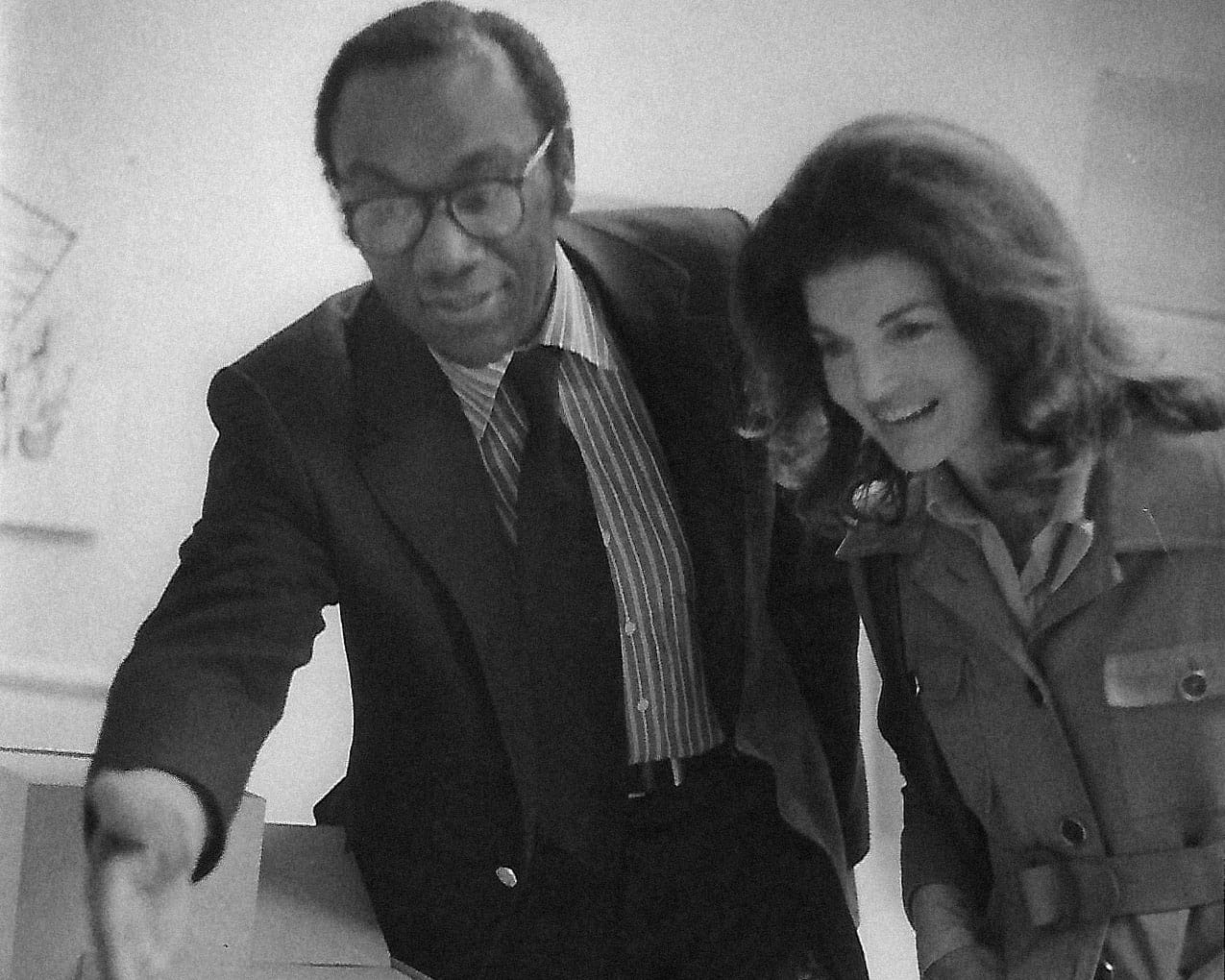

Thomas shares the creations of Design Works, a community initiative conceived with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, right, as part of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation.

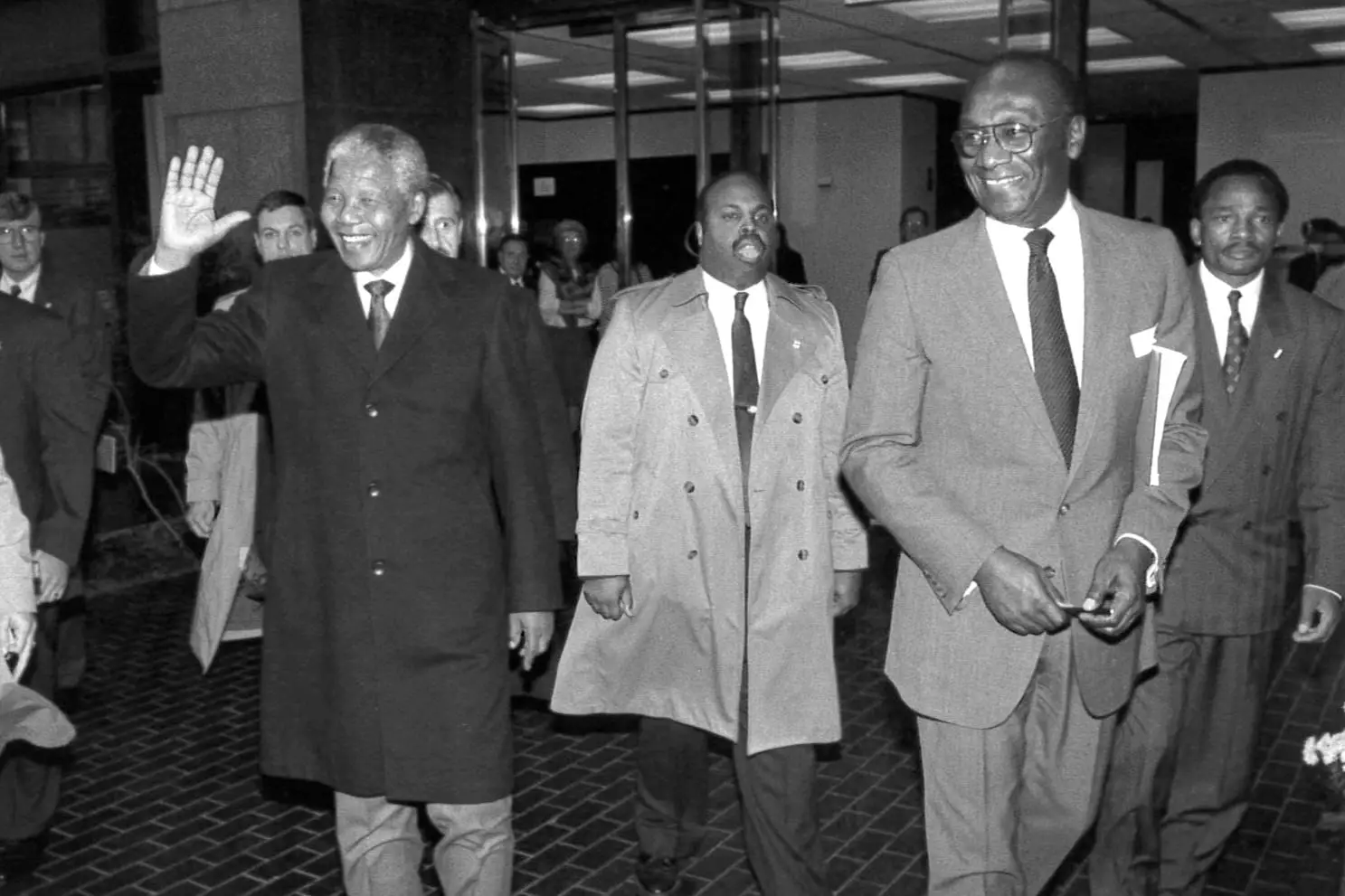

During his Ford presidency, Thomas, right, became an indispensable ally of the anti-apartheid movement and forged a partnership with Nelson Mandela, left, before establishing the foundation’s first office in South Africa.

At the Ford Foundation, Frank’s perspicacious voice still echoes and his long shadow still looms. During his tenure as president from 1979 to 1996, Frank presided over the groundbreaking Study Commission on US Policy toward South Africa, an indispensable ally of the anti-apartheid movement—and forged a fateful partnership with Nelson Mandela, championing South Africa’s constitution and opening the first foundation office in the country. He also helped to establish the Local Initiative Support Corporation, which has supported countless neighborhood revitalization efforts.

And in our own institution’s most perilous hour, after a 90 percent depletion in our endowment’s real value during the 1970s, Frank courageously rescued us from insolvency. He made painful, unpopular decisions that set us on a path to long-term sustainability and made possible two generations of impact to follow.

Decades after his 17-year tenure as Ford president, Thomas’ perspicacious voice still echoes and his long shadow still looms in the halls of the foundation.

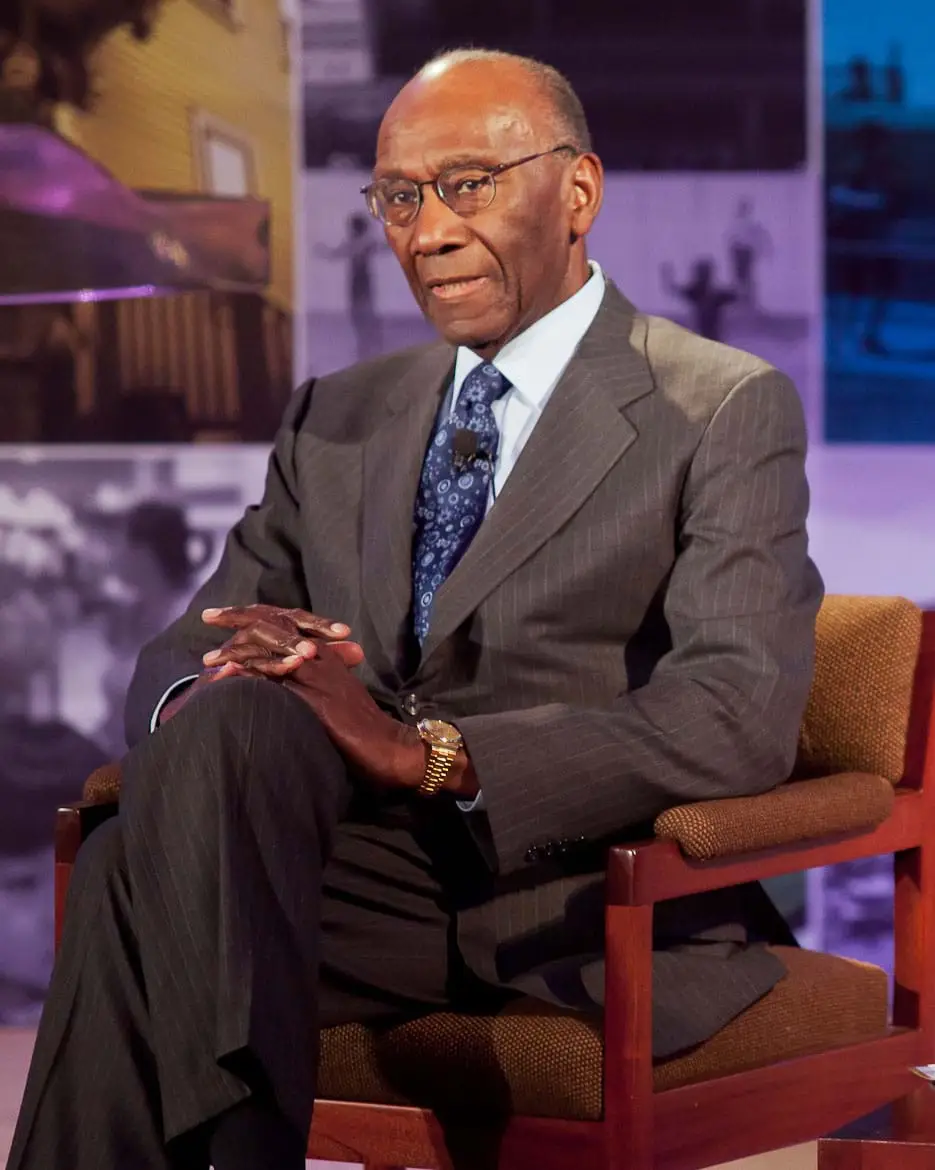

While Frank surely changed the world, perhaps equally remarkable is what never changed about Frank: his humility, his generosity, his equanimity. Long after his tenure at the Ford Foundation, he made time to dispense wisdom and perspective from a small office in the Chanin Building on East 42nd Street, guiding me through good times and bad.

He taught us all to do the right things in the right way—to act with righteousness, not self-righteousness. To be in Frank’s presence was to feel awe, reverence, and gratitude. I miss him, and appreciate every word and every moment we shared.

Today, my thoughts are with Frank’s beloved wife Kate, his four children, Kyle, Keith, Hillary, and Kerrie, and the entire Thomas family.

Let us all strive anew for the equanimity that Frank so graciously, gracefully embodied.