Priscilla Smith was just 19 when she learned what it meant to be a caregiver. Her father, a taxi driver who ferried people around Fayetteville, North Carolina, or as far away as New York City, was diagnosed with prostate cancer. She watched, helpless, as he tried to navigate the medical system as a Black man on Medicaid: waiting five or six hours to be seen by a doctor, told he was ineligible to receive nursing support at home because the officials he encountered assumed his complaints were due to laziness rather than pain.

The experience inspired Smith to get certified as a nursing assistant. “Once I became certified,” she said, “I wanted to know who else out there was going through the same thing.”

She quickly discovered she was not alone. Over the course of a decade, Smith has worked across the caregiving map: as a home health aide providing support to aging and disabled clients; in skilled nursing facilities; and, these days, as a family caregiver, as she cares for an adult daughter with special medical needs and a two-year-old foster child. What she’s seen in all those situations is a system that’s badly, but invisibly, broken: the contours of a care crisis that’s already begun to overwhelm the United States.

For most of her life, Priscilla Smith has worked as a caregiver until recently when her daughter was diagnosed with a chronic illness. While she is in essence doing the same job, from organizing medical appointments to cooking and caring for her and her foster child, she isn’t compensated and struggles to support her family. Footage by Bridgette Cyr.

As a home health aide, Smith worked with aging or disabled clients who wanted to live at home but weren’t authorized—by the state or their insurance companies—to receive enough hours of support to address their needs. It often left Smith just enough time to get them dressed, make their beds, and fix them a quick meal, then worry about what might happen in her absence.

“A good caregiver’s job doesn’t stop because they’re leaving the patient’s house or the facility,” she said. “They want to know that the patient is OK in the middle of the night. Did another caregiver get their bath clothes, or remind them to brush their teeth, or heat up their food to the temperature they like?”

The sparse amount of care clients receive also affects aides themselves—overwhelmingly women, immigrants and people of color—who typically get paid little more than minimum wage and aren’t compensated for the time it takes to get from one client’s home to the next. Smith watched as skilled home care aides left for nursing facilities, where they could at least be guaranteed enough hours to make a living.

From her work in those facilities, Smith knew that heavy caseloads meant care was stretched thin there as well, with nursing assistants often responsible for 15-20 patients a day, leaving little time for individualized care. While at home, the focus was on ensuring clients’ comfort, the guiding mandate in nursing facilities was “hurry up and get the job done, by any means necessary.”

“Everyone deserves the same amount of care, at the same level, with the same respect and love. But it’s not given that way,” Smith said.

“Everyone deserves the same amount of care, at the same level, with the same respect and love. But it’s not given that way.”

Priscilla Smith

Then, when her youngest daughter, Zeroniaque, was diagnosed at 17 with neuromyelitis optica, a condition similar to multiple sclerosis, Smith became a family caregiver again, compelled to stop working to focus on her daughter’s care. And although she’s doing the same job she performed professionally for years, it’s not work she’s compensated for by the state, since North Carolina’s process for recognizing family members as paid caregivers is prohibitively complex.

“It didn’t make any sense to me, because who loves your child better than you? Who loves your parents better than you?” asked Smith. “In my experience, 98 percent of the time, the family member is going to do a better job, not only because they’re emotionally attached, but because they know that person best. And in caring, all of this matters.”

In many cases, situations like this become catastrophic: people, usually women, drop out of the workforce to care for a family member and become impoverished themselves. Smith has seen people end up in public housing or homeless, and their loved ones land in group homes because their families can no longer afford their bills. In the last year, Smith had to move her own family into a long-term hotel because she couldn’t afford a home after giving up her job to care for her daughter and her foster child, Iamrya.

But it’s also the sort of calamity that tends not to be seen: a mass epidemic of private family disasters, happening out of sight.

The care crisis in the US is interconnected, impacting the elderly who are living longer and require assistance, underpaid caregivers, who are mainly immigrants and people of color, and women who are torn between work, taking care of their children and tending to aging parents. Footage by Kali 9, Pigeon Productions, Inc. and Sean Anthony Eddy.

The work that makes all other work possible

Care work is the work that makes all other work possible, whether it’s professional or unpaid family care, care for children, the elderly, or people with disabilities. In all permutations, in the United States, it’s also work that’s both undervalued and unseen.

Care has long been invisible in society. Why? Because the care consumers—such as the elderly and people with disabilities—are invisible. And the people who provide that care—mainly women of color—are invisible.

That means that the crisis of caregiving has long been invisible too, playing out in isolation, as families struggle to find and pay for childcare and the aging or illness of a loved one, all while maintaining an income and taking care of themselves. But, as a country, we’re not used to seeing it as one overarching, interconnected problem, since its constituent parts have so long been treated as separate issues.

From one perspective, it’s a crisis for people with disabilities and seniors. America faces a cresting “elder boom”—what economists call “the Silver Tsunami”—of aging Baby Boomers who are living longer than ever and desire to remain in their homes, but need help to do so. People with disabilities, who have long experienced inequities and ableism throughout the healthcare system, are far more likely to require home health care or institutional assistance than non-disabled people and experience barriers to access, particularly during the pandemic.

Home healthcare workers are typically paid a starting salary of $13,000 a year, often without benefits.

Take a step back and the care crisis is a labor crisis as well, involving both the issue of an inadequate workforce supply to meet growing demand, and the deeply related question of how little the US values the hard work of caregiving. Home healthcare workers are typically paid a starting salary of $13,000 a year, often without benefits, leaving many dependent on public assistance for their own family’s needs. In most states, they are still excluded from collective bargaining or basic workers’ rights. All this leads to low worker retention and high turnover, as workers leave the field for easier, better-paid jobs.

From another perspective, it’s a childcare crisis, as families grapple with daycare costs that can easily consume 20 percent of their income.

That also makes it a crisis for women, still the primary caregivers in most families, responsible for both children and ill or aging family members. Many end up in the growing “sandwich generation”: squeezed between the competing demands of caring for young children, aging or ill parents, and maintaining a career.

Ten years ago, that was me. I was co-directing a national organization and working to co-found another, while becoming a new mother. In the midst of all that, my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. It was the start of a years-long journey to help navigate my father’s care.

Even as an advocate steeped in the intricate bureaucracies of America’s healthcare system, Ford’s Sarita Gupta was struck by its complexities when her father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and she had to manage care for both her parents and daughter. Footage by Tim Persinko.

It should’ve been easy, after all I’d spent my career thinking about what care looks like in America. Before directing Ford’s Future of Work(ers) program, I served as executive director of Jobs With Justice Education Fund, which helps organize workers, including those long excluded from traditional labor unions, like home healthcare workers. That led to my co-founding Caring Across Generations, a coalition to unite caregivers and care recipients, and a Ford grantee since 2011. These days, I try to help the world of philanthropy understand how interconnected the care crisis really is.

But when trying to help my parents address their needs, I found the care system incredibly difficult to navigate, even as an advocate steeped in its intricate bureaucracies. I thought to myself, it shouldn’t be this hard.

Compared to many, I was in a privileged position. Faced with untenable costs for both child and elder care, many women are pulled out of the workplace to become full-time caregivers, forfeiting hundreds of thousands of dollars in wages, benefits, and savings for their own retirement along the way. And usually, families navigate these sacrifices in silence and isolation.

Until this past year, when COVID-19 made the care crisis so universal and so glaring that, for once, it couldn’t be ignored. Before the pandemic, we already knew the caregiving numbers don’t add up. Sixty percent of the US workforce earns less than $75,000 per year, while annual childcare costs start at $10-16,000, and nursing homes at $80-100,000. While people assume that Medicare or Medicaid will cover the expense of long-term care, many families find out the hard way that that’s simply not the case.

As COVID brought the country to a halt, families with elderly or disabled members lost the support of home health aides who made the delicate balance of their lives work. Adult children with parents in nursing homes were torn by wrenching decisions as COVID swept through facilities, and some parents who ended up hospitalized with the virus lost their bed at the home, meaning once they recovered, there was no place to get the care they needed.

With schools and daycares closed, leaving millions of children at home, middle-class parents were faced with impossible work-life demands that lower-wage working families have long suffered. Parents—particularly mothers—have been left without childcare they’d long relied upon. In September alone, said Fatima Goss Graves, president and CEO of National Women’s Law Center, a Ford grantee, the pandemic led to a historic departure of women from the workforce as the school year restarted. By the end of 2020, 2.2 million dropped out of the workforce.

But the problem will soon get worse, as two of America’s largest generations are creating an unprecedented demand for care. Baby Boomers are retiring at a rate of 10,000 people per day and living 20 years longer than when Social Security was enacted. Over the next five years, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates, more than half the workforce will be caring for an aging adult. Meanwhile, Millennials are having children at a rate of four million per year. Meaning the sandwich generation is about to get a lot bigger, a lot more squeezed and, in most states, lacking the most basic protections like paid family leave.

“Part of the dysfunction of our care system is that it was built on the longstanding idea that it’s OK to pay a largely Black and brown workforce poverty wages,” said Graves. “And that’s not a sustainable idea. So when it crumbles, maybe no one should be surprised.”

But another part of the issue is that America hasn’t conceptualized all of these individual problems—the personal catastrophes taking place in private homes, the inability of professional caregivers to sustain themselves while supporting other families—as aspects of a shared problem that society needs to tackle as a whole.

Over the last decade, advocates and care workers have come together to shed light on the interconnected issues of care and develop solutions that cover the spectrum of needs across a whole lifespan. Footage by the BBC Motion Gallery Editorial, Othello Banaci for NDWA, and Nexstar WGN-Chicago.

Building a blueprint to fix a broken system

Over the last 10 years, I—along with longtime labor advocate Ai-jen Poo, founder of the National Domestic Workers Alliance and a Ford Trustee—have tried to make exactly that case: to redefine America’s understanding of care and envision a new, more holistic and equitable approach to providing care. Our definition of care protects both workers and families and emphasizes the importance—and interconnectedness—of childcare, elder care, long-term care, paid leave and workers’ rights. Too often, these interests are pitted against one other, but they don’t have to be. A problem as intersectional as the care crisis can only be solved by an equally intersectional solution.

Building a movement in support of a new care infrastructure has been a long road, shared with many partners and allies that have fought to address these interconnected issues. The Ford Foundation has provided bedrock support for many of these movements, from its early investment in advocates for the 1992 Family Medical Leave Act to its seed funding for a consortium of state-level paid leave advocates. The latter eventually evolved into Family Values at Work, a key player behind the successful passage of paid leave laws in nine states and Washington, DC as well as a pivotal partner in the movement for a new care infrastructure.

Ford also provided foundational support for a movement that emerged in the late 1990s and 2000s to help organize workers outside the reach of traditional unions, including the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, Poo’s NDWA, and my own Jobs With Justice Education Fund.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

While these might seem like very different tracks of funding, we came to realize that all were vital parts of envisioning a new definition of care. As my colleague Anna Wadia, senior program officer for Ford’s Future of Work(ers), put it, “We knew the two—policy and organizing—needed to be very connected. We believed that policy change needed to come from the grassroots up, with the experiences of people providing care front and center.”

For example, in the late 2000s, Poo and I began hearing from nannies and housekeepers that their jobs were changing—they were being asked to also care for their employers’ aging and ill parents. “America’s families were feeling the pressure of the increased need for care on the part of the growing aging population, and they had no support,” Poo said. “So they were going to the people who supported their families already—the domestic workers.”

We realized a demographic shift was coming, and we, as a country, were not prepared. That realization led to a vision: we needed to think about care across the spectrum of a whole lifespan—childcare to elder care and everything in between—and make known how those needs arise across generations within a single family.

In 2011, with support from Ford, Poo and I built Caring Across Generations with the aim to advocate for both quality, affordable care for all Americans and dignified, equitable jobs for caregivers. As we went knocking on doors to spread the word, we heard from families about other needs too: their inability to take paid leave when a parent had a stroke, childcare so expensive that one parent had to quit a job to stay home, or the demands of working and caregiving that felt like impossible burdens to balance. Families were being forced to make incredibly hard choices: do they pay for college or elder care? Invest in their children, or care for the parents who raised them?

We also saw that the lines around caregiving work were blurry: while a family’s care support includes workers, care workers are also part of their own families, facing all the same stresses as their employers and clients—and the reality of their own future care needs as they age.

We knew we needed to help the public understand how interdependent the care workforce and the families it supports are. How the interests of care recipients cannot be separated from the interests of caregivers—both paid and unpaid—without both suffering.

Early on, we created Care Councils: groups that brought together different stakeholders—home health aide workers alongside their aging or disabled clients—to think through solutions to the interconnected issues they faced.

“It can be really easy to pit workers in a situation against people receiving benefits from it, including but not just in care,” said Erica Smiley, who now runs Jobs With Justice Education Fund, a Ford grantee. “We believed that if care workers and care recipients were at the center of setting policy, it would actually be better for everyone.”

We knew the care crisis needed a bold, integrated and game-changing approach to put this vision into practice. That’s where the idea of Universal Family Care (UFC) came about: a program designed to meet families’ caregiving needs from birth to death.

“We believed that if care workers and care recipients were at the center of setting policy, it would actually be better for everyone.”

Erica Smiley

A core aspect of our vision was structuring UFC as a social insurance program, much like Social Security or Medicare, where everyone contributes and everyone benefits—something that generates both bipartisan support and a widespread sense of ownership. To translate that idea into policy, Ford introduced Caring Across to another grantee, the National Academy of Social Insurance, a Washington, DC think tank that specializes in tackling the deep technicalities of policy ideas. Together, with support from Ford, we produced a 300-page roadmap: Designing Universal Family Care. Our message was that rethinking the care system was bold, necessary, and—most importantly—possible.

The UFC vision of a comprehensive care plan provides everything from childcare and long-term care for the aging and disabled, to fair pay and dignified working conditions for professional caregivers. It was designed to be a one-stop shop for every family, allowing them to pay for the care they need, when they need it. Just bringing resources together would be revolutionary in helping people navigate existing models of support. But the benefits of UFC would also be portable, designed to fit the realities of people’s modern work lives.

“The idea of Universal Family Care just made sense to everyone on a guttural level,” Smiley said.

It also makes the academy’s CEO William Arnone hopeful that bold care reforms might avoid some of the intractable polarization that has stymied other ambitious legislation in recent years. “I don’t want to be naive about the policy world we live in, but this issue affects everyone,” he said, citing a famous Rosalynn Carter quote: “There are only four kinds of people in the world: those who have been caregivers, those who are currently caregivers, those who will be caregivers, and those who will need caregivers.”

As he puts it: “This is one of those we’re-all-in-this-together areas. It’s a universal risk. If ever there was an issue that could be a harmonizing issue, this has all the hallmarks.”

Care, whether tending to children, supporting people with disabilities, or managing the home of an elderly person, connects us all, but it’s only beginning to be seen as one, united issue in the US. Footage by Funky-Dat, Chee Gin Tan and FG Trade.

The True Cost of Care

One of the biggest challenges in addressing the complexity of the care crisis—and transforming the vision of Universal Family Care into working policy—is how diffuse the current patchwork of care systems can be. Policies related to elder and disability care, childcare, and paid family leave are all handled by different branches of government. The result is that advocates for each issue—which share so much in common, but are treated separately—are left fighting for the same resources.

“We know that people at the state and federal level are fighting for improvements,” said Ben Veghte, director of the WA Cares Fund, the new universal long-term care program in Washington State. “But they’re competing with each other for the same pot of money in the same political real estate. The insight of Universal Family Care was to ask, “Why are we competing when ultimately, in families, this all comes together? Why are we separating these into three different issues when it’s really just one?”

This message has begun to resonate across the philanthropic world. In May, the Ford Foundation, along with a number of partners, proudly announced The Care for All with Respect and Equity Fund (The CARE Fund). The $50-million, five-year collaborative fund, inaugurated in partnership with several other philanthropies including the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Pivotal Ventures, and Schusterman Family Foundation, is intended to model an intersectional approach to the care crisis, and inspire other funders to think about care in a holistic and interconnected way.

While advocates have already radically re-envisioned childcare, paid leave, elder and disability care and the care workforce as one, united issue, funding streams have remained siloed, helping prop up artificial distinctions that pit one aspect of the care economy against another. But COVID-19 and its converging crises have given us an unprecedented opportunity to reckon with the failures of our care system, as the country witnessed en masse what happens when families lack access to quality, affordable childcare or eldercare; when care systems and facilities can’t ensure the safety of those in their care; and when workers must choose between their health and their livelihood. The uniquely universal recognition of these problems gives us a real chance to build a new and powerful movement for care.

“This is the moment,” said Wadia. “The field is aligning, and it’s time for foundations to mirror that and come together to support this as one movement, where everyone sees the value of care no matter who and how it’s provided.”

This support—and this understanding—couldn’t come at a more critical time. Since rolling out UFC, states like Washington and Hawaii have passed legislation to implement some aspects of the plan (in addition to the states that have advanced paid family and medical leave). The clear standout among them is Washington, which in 2019 passed the first-ever public program for universal long-term care, with leadership from a broad coalition called Washingtonians for A Responsible Future, led by the Service Employees International Union Local 775, in partnership with Caring Across, AARP Washington, and many others.

Starting in 2025, the landmark program, funded as a social insurance initiative through worker contributions, will offer Washington residents a flexible benefit of $36,500 for any long-term care needs that arise. A working mother whose parent becomes ill, for example, could either use the funds to hire a home health aide, pay for care in a nursing facility, or take time off work and be compensated for her own caregiving.

“It gives her choices,” said Veghte. “It allows her to keep earning money, so she can put a roof over their head and keep saving for retirement. It keeps families on track to remain in the middle class.”

At the federal level, Joe Biden, during his run for the presidency, announced that caregiving would be a core plank of his economic agenda, with plans to invest $775 billion in caregiving infrastructure. For an issue that had long been considered a special interest diversion—just “a woman’s issue,” or “a labor issue”—it was a breakthrough to see care be treated as a cornerstone of a presidential candidate’s economic agenda.

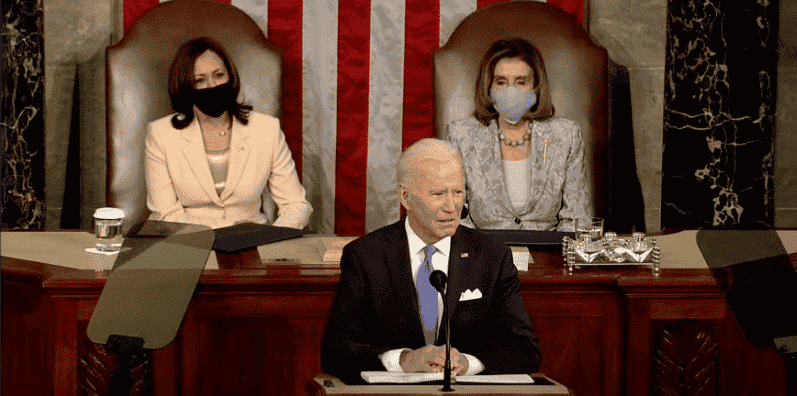

Then March brought the historic news that the Biden-Harris administration’s $2-trillion American Jobs Plan, includes $400 billion—the largest single line-item—to support in-home care for seniors and people with disabilities and address historic inequities in the labor force providing that care. And, just last month, the administration rolled out the $425-billion American Families Plan that includes a comprehensive paid family and medical leave program along with investments aimed at making high-quality childcare accessible.

It’s hard to overstate how exciting this is. Ten years ago, nobody could imagine policymakers centering paid leave, childcare, long-term support and services, and workers’ rights all in the same discussion. But talking with everyday families, and thinking through the values that underlie the call for a universal care framework has prompted people to ask why America doesn’t have a system that covers the whole lifespan of care needs. And just asking those questions has opened up a space for the amazing policy opportunities we now face.

While COVID-19 has amplified the importance of care and brought essential workers and their issues to the halls of Congress, the crisis has become too big to ignore. Footage by Apomares, Othello Banaci for NDWA and Lighthouse Films.

Care can’t—and won’t—wait

But it won’t be an easy road. While people are strongly supportive of UFC and a larger care infrastructure, that consensus can break down around particulars about what the government’s role should be, what it will cost, and between people who care more about one aspect of the care crisis than another—quality and affordability of services versus making caregiving jobs good jobs.

“We want to make these jobs honorable jobs. Because it’s not just a job. I am a caregiver.”

Priscilla Smith

We care about all of it. But we can no longer ignore that the care crisis is unsustainable in both economic and human costs. The pandemic has made that all too clear, as the care crisis becomes more broadly visible than ever before. There’s simply no way, absent large-scale, publicly funded programs, that American families can afford the care they need on the wages they earn. And the scarcity model that has long justified paying poverty wages to caregivers—and pitted them against the interests of families receiving care—has only led to catastrophe, for individual families as well as the country at large.

But that also proved one of the few upsides of an awful year: a conceptual leap in the public conversation about care, when the many interconnected problems families and workers have grappled with privately, became inescapably evident.

“America’s culture of individualism has created a context where people see the responsibility of caring for their family as a personal burden of responsibility,” said Poo. “If for some reason you can’t afford childcare or find the right home or care for your aging parents, it’s because of some failure on your part. It’s not your fault. Care connects us all. This is a shared, systemic challenge that needs public policy solutions. One of the silver linings of this pandemic has been that shift in consciousness.”

It’s thanks to care workers like Priscilla Smith, who is joined here by her two-year-old foster child, that the issue of care is becoming more visible and more urgent than ever before. Footage by Bridgette Cyr.

Tackling that challenge will require getting the public to see their private, invisible care dilemmas as part of a larger, shared struggle. That’s the work ahead, but thankfully we have caregivers like Priscilla Smith working hard to make that happen. Alongside caring for her daughter and foster child, Smith is also an organizer with NDWA’s We Dream In Black chapter in Durham, North Carolina. As an advocate, she’s lobbied for state and federal legislation, including last year’s Heroes Act, which recognized domestic workers as essential workers: the indispensable backbone of both individual families and our economy at large.

“We want to make this work a prideful work, to make these jobs honorable jobs,” Smith said. “Because it’s not just a job. I am a caregiver. I am the person who’s loving and caring for your parent. I am the person you trust with your loved one. So trust me, respect me. And give me what I’ve earned and deserve.”

The Ford Foundation has been honored to support the movement for care for many years, including the organizations in this piece along with many others. For more information on our grantees’ work, we encourage you to visit their websites: A Better Balance, Center for American Progress, Center for Community Change, Center for Law and Social Policy, Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Main Street Alliance, MomsRising Education Fund, National Partnership for Women and Families, Inc., Paid Leave for All, PHI, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and Zero to Three.