Making Eyes on the Prize: Telling the Story

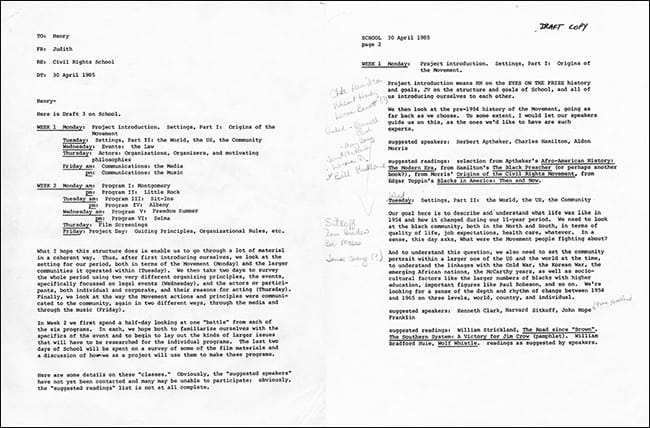

Henry Hampton didn’t want Eyes on the Prize to rehash the civil rights movement many Americans thought they knew. He wanted to tell a broader, bolder, messier story. He brought in a range of activists, scholars, and artists to give his teams a crash course in this new narrative—a process he called “school.”

Judith Vecchione

In the old screening theater at WGBH, which was not a big room, we would bring in scholars, activists, journalists, and people who lived the history, and thrash our way through. We had a short period of time to figure out who we were, what we were doing together, and how we were going to do it. School was talking about stories and people and events and the larger history that framed it; how do you treat it, and what media is available.

Kenn Rabin

It was like going to grad school for free. You’ve got a subject that you’re interested in and would be entangled with for the next three years.

Sheila Curran Bernard

Eyes school, including the extensive reading we were assigned beforehand, was life changing, an entrée into a history and communities that I have never stopped appreciating.

Laurie Kahn

We had hundreds of pages to read every night, excerpts from articles and books. The people who were there each day were the best scholars in the field. So we all got completely immersed in the subjects and also got to know these scholars. Later in the project when we had a question, we all felt comfortable picking up the phone and saying, “I’m stuck, can you give me some advice?”

Kenn Rabin

We had Odetta, the folk singer, come. We had Guy and Candie Carawan, who wrote “We Shall Overcome.” They taught us some of the songs that were sung by the movement. We got the sound of it in our heads. Bernice Johnson Reagon talked about what music was being used in what city. Then we had other people who came in and lectured us about everything from the flat-out history to the motivations behind the children’s march to the tension between the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] and SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee].

Callie Crossley

You did not know which two episodes you [would be assigned to produce], which was deliberate on Henry’s part. That meant you had to pay attention during school. You had a base level of information about everybody’s episodes. You knew you were not just an island, that things had to happen across the series to make sense.

Laurie Kahn

Henry insisted that each team be one male, one female, one black, one white. That was the formula for every single team. So Judith, a white woman, was paired with Llew Smith, a black man. Callie Crossley, a black woman, was paired with Jim DeVinney, a white man. Orlando Bagwell, a black man, was paired with Pru Arndt, a white woman. It seemed arbitrary, but I’ll tell you, it did have an impact on how those films took shape. People brought different life experiences to how they saw the history and how it impacted them.

Jon Else

Henry was very insistent that we find and solicit what he called testimony against interest, getting people on the witness stand who disagreed with you. There were very few white segregationists who would talk to us because they had landed on the wrong side of history, but Henry insisted that we find them.

Callie Crossley

This is not a black and American story. It’s just an American story. Henry said, I want you to make certain that people can look at this and see where the principles of democracy are playing out, and that people were willing to sacrifice.

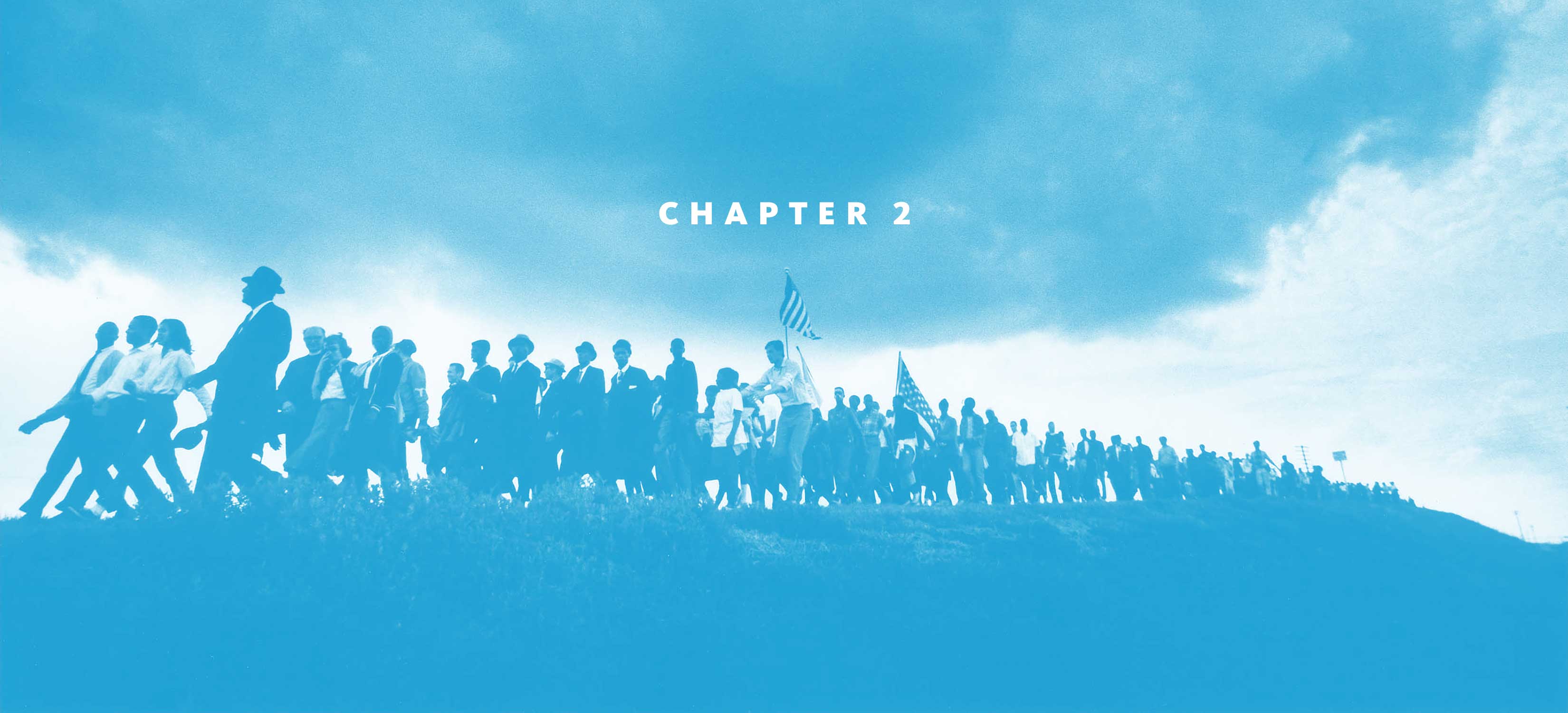

Jon Else

Henry also insisted that we load it up with American flags. He said, “It’s our flag too.” So it’s an extremely patriotic piece of filmmaking.

Laurie Kahn

The place was nonhierarchical: Good ideas are good ideas, no matter where they come from. At staff meetings, it wasn’t just producers and associate producers and Henry. Everybody was welcome to speak up. It reinforced the sense of mission. All that mattered was making these films the best films they could be and getting the history right. There were knockout, drag-out fights at times, but they were the right kinds of fights. They weren’t over ego and who had a corner office and who had windows. It was about how to make the best films possible.

Jon Else

We were all part of every conversation, yeah. Blackside was never a democracy. Henry was always in charge, but it was an outfit that operated by extreme collaboration.

Once the teams had their assignments, they began collecting images and stories that would show viewers how the grassroots civil rights movement had sprung up in communities across the nation. It was an archival scavenger hunt.

Laurie Kahn

Before Eyes, films about the civil rights movement used footage from the national networks. You saw the same shot over and over again, and the focus was on Martin Luther King Jr. Henry’s focus was on the foot soldiers of the movement. It is history from the bottom up rather than the top down, understanding the ways ordinary people were able to make a difference and what they were up against and what their strategies were. It was not like King just swooped in and changed the world.

Louis Massiah

Leadership is something that’s easy and convenient for national media. It’s easier for them to talk to one person and define that person as being the movement, as opposed to the people who are involved in the day-to-day grind and putting their lives on the line.

Sue Williams

I loved looking at footage. You might stumble upon something really useful that would just kind of open up a story. It would add flavor and context. You were seeing this history come alive, more immediate than the books.

Andrea Taylor

Henry’s dream was to tell the story from the perspective of the ordinary people, the nameless, the faceless, the unknown, who were out there in communities risking their lives and livelihoods every day, marching, demonstrating, protesting, boycotting. There were iconic people that you knew, but you didn’t know a lot of the ordinary people who had reached the point where they were sick and tired of being sick and tired. When Henry and his team went to find documentation for their production, these voices weren’t in the archives.

Laurie Kahn

Step one was to find all the local TV stations, anywhere one of the stories that we were telling took place. I got on the phone and called all of them. I also found out who was shooting photographs locally and then spent a lot of time tracking them down, digging in people’s attics and basements and garages with them to find stuff—or the back room of a local TV station in Birmingham.

Some of the best footage of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom had been shot for the United States Information Agency (USIA), which produced it as a documentary for overseas audiences. But laws prevented the American public from accessing this and other films the agency produced, putting it out of reach of the Eyes team. In 1986, Laurie Kahn enlisted congressional help to change the law and expand access to the rare and revealing USIA films.

Laurie Kahn

The teams were editing the footage we had of the March on Washington. These shots had been in every film on the civil rights movement. The Eyes teams wanted footage of people preparing sandwiches and placards, in buses and trains and cars coming in from all over the country. They said, “We want them walking to the Mall. We want them setting up the seating. We want people wading in the wading pool on the Mall. We want close-ups of people’s faces.”

Laurie Kahn

I had two and a half months [to get it done]. I enlisted someone from Senator Kerry’s office in the Senate and somebody from Barney Frank’s office in the House. We tried to attach it as a rider. The bills didn’t pass. Finally, they said, “Let’s just introduce it as a freestanding bill.”

Kenn Rabin

Congress passed a new law, and Reagan signed it. We had our USIA film.

Lyric Cabral

Let’s say I go to get a speech from Malcolm X in Harlem in 1958. Unfortunately, if someone hasn’t requested it before me and digitized it, it may very well be in the state that it was in in 1958. Untouched. Eyes on the Prize popularized these pieces of archives. They’re now in the system. It created an archival starting point for in-depth research or for people like myself. If a body of work is not digitized, it’s much harder for someone coming in from the outside to even start the process.

While the archival team looked for footage, producers and camera crews traversed the South, interviewing the foot soldiers of the black freedom struggle. Many of them had never told their stories before the Eyes team entered their homes.

Sheila Curran Bernard

We’d work together on questions beforehand, and collaborated on treatments, so we knew what we were hoping to get out of the interview and where it might fit into the overall film (also leaving room for surprises and opportunities that can’t be foreseen).

Callie Crossley

Here comes Jon Else, and he gathers us all up. He wrote on the board how many people had been pre-interviewed, how many people they came up with in the end. Just a formula to let us see that there’s a lot of pre-effort put into narrowing down on a story. He said, “When we get to the field, I want you to remember this: Do not confuse a good time with a good film.”

Orlando Bagwell

Many of the stories arose from experiences people had never talked about. Often they broke down—remembering danger, or the death of a colleague. We the filmmakers knew we were requesting precious memories, both joyful and frightening. We had to be extremely conscious of not only how we asked questions but also of the path we needed to take so they spoke from the personal experience and not from a place of history.

Judy Richardson

When I’m interviewing, the important thing is to look at a person. I’m not looking down at my notes. I tell the interviewee, I’m going to be very quiet during this. But I’m doing a lot of head movements. I’m smiling, putting my shoulders up and down. It’s almost pantomime, because I want them to feel that I’m really responding to what they’re saying; we’re just not hearing the vocal part of it.

Jon Else

It’s your job to be a skeptic and to force the issue. Callie Crossley was interviewing Governor Wallace about his incendiary rhetoric in the 1960s. He tried to say, “Oh, it has nothing to do with race, and it has little to do with segregation.” It was all about the federal usurpation of power. It’s all about state’s rights. Callie was a young African American director, and she was the age of those young girls who were killed in the church in Birmingham. I think she felt a moral and a personal obligation to say, “Hold on, Governor.” So, we are always doing that balancing act.

Callie Crossley

You make the interview subject comfortable. That does not mean that you ever lie to them. You don’t say, “I want to talk about the love letter your grandfather wrote to your grandmother,” and get in there and say, “So I hear you murdered your wife.” You don’t do that. We said, “We’re coming to talk about your participation in the civil rights movement.”

Judy Richardson

My movement experience is what taught me how to do interviews. Subjects have to get a sense that you are authentic. That you are not some fake person. That they trust you to tell this story true, in a way that they recognize as theirs. That you have not manipulated it, that you are telling it well.

Jon Else

Many of the white staff felt it would be hypocritical for the resolutely multiethnic, multiracial, multicultural outfit like Blackside to show up at an interview with an all-white or an all-black crew. Many of the black staff disagreed. I remember Callie saying, Leave the white people at the hotel or leave the black people at the hotel—whatever you have to do to get Mr. Jones or Mrs. Jones to speak honestly. So there were occasions when we had all-black or all-white film crews, simply to allow the person being interviewed to be more comfortable in speaking their own truth. We used an all-white crew with the president of the White Citizens’ Council. We used an all-black crew with some of the black nationalists from the 1970s. We were uncomfortable with it, but I think we never doubted that it was the right thing to do.