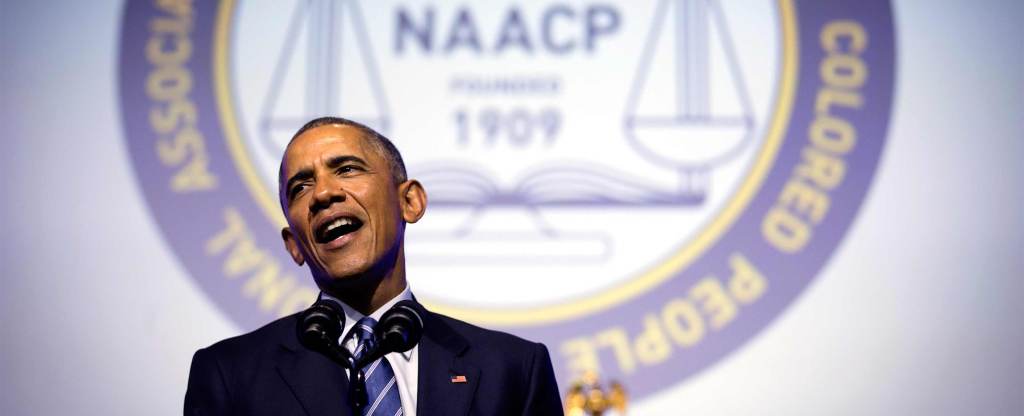

In commuting the sentences of 46 people charged with drug offenses on Monday, President Barack Obama remarked, “Right now, with our overall crime rate and incarceration rate both falling, we’re at a moment where some good people in both parties, Republicans and Democrats, and folks all across the country are coming together around ideas to make the system work smarter, make it work better.” The following day, the president delivered a sweeping indictment of the criminal justice system at the NAACP’s annual convention in Philadelphia, calling for major reforms, including revising mandatory minimum sentencing, improving prison conditions, reviewing the use of solitary confinement, restoring voting rights for those with felony convictions, and ensuring formerly incarcerated individuals have a fair chance to work. This also coincides with Obama’s trip to El Reno today, making him the first sitting president to visit a federal prison.

These efforts represent an enormous shift in the nation’s outlook and are emblematic of a rare opportunity that has emerged in recent years: to pursue comprehensive criminal justice policy reform based on equity, public safety, and proportionality. They also come at a time when the nation finds itself at a crossroads in its racial history and conception of justice. From Ferguson to New York City and Baltimore to North Charleston, the country has witnessed—again and again—unarmed African-Americans dying at the hands of law enforcement. The inspired work of criminal justice advocates, the bold leadership of those directly affected, including formerly incarcerated people and victims and survivors of crime, and the courageous grassroots activism that has grown in response to these incidents are forcing the country to confront disparity and come to terms with the profound impact of the system on peoples’ lives.

The United States currently holds the notorious distinction of being the global leader in incarceration. The massive expansion of the U.S. criminal justice system in the past four decades has devastated communities, broken up families, exacerbated racial and gender disparities, contributed to mounting inequality and cost the country billions each year. For instance, between 1980 and 2013, the federal imprisonment rate grew 518 percent, while annual spending on the federal prison system increased by 595 percent. People with drug convictions now make up almost half the federal prison population. Marijuana arrests account for over half of all drug arrests in the U.S., and despite roughly equal usage rates, blacks are almost four times more likely than whites to be arrested for marijuana. And according to the Pew Research Center, in 2010 black men were more than six times, and Hispanic men nearly three times, as likely to be incarcerated as whites.

Nevertheless, as a result of the economic downturn and fiscal pressures, decrease in violent crime rates, and shifting public attitudes of marijuana and other drugs, there is genuine momentum to examine justice issues and bipartisan interest in reassessing corrections at both the state and federal level. While prominent federal officials—most notably, former Attorney General Eric Holder—have made encouraging statements proclaiming the need for a fundamental shift in the country’s approach to corrections and law enforcement, the most innovative action has taken place at the state level. For example, California voters approved Proposition 47 in November 2014, which requires all drug possession offenses and theft offenses for goods valued at less than $950 be sentenced as misdemeanors. The Sentencing Project notes that in 2014 alone, at least 30 states passed legislation seeking to reform some aspect of how their criminal justice systems address sentencing, probation and parole, as well as collateral consequences that amount to a lifetime of civic, economic, and political punishment.

What’s more, groups led by formerly incarcerated people—like JustLeadershipUSA, A New Way of Life Reentry Project, All of Us or None, Southern Coalition for Social Justice, Families for Justice as Healing—are working to ensure the needs of those most affected are central to reform. States and local jurisdictions are further implementing innovative pilots to ensure more comprehensive and responsive justice delivery. Examples include Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), an initiative that operates in King County, Washington State, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, where it provides police officers with the authority to divert low-level, non-violent drug and prostitution offenses from incarceration to social services, and Vera Institute’s Common Justice, an alternative-to-incarceration program that works with young adults who have committed violent felonies and seeks to address the emotional, material, and social needs associated with certain serious crime.

In President Obama’s commutation statement, he also said, “I believe that at its heart, America is a nation of second chances. And I believe these folks deserve their second chance,” adding “There’s a lot more we can do to restore the sense of fairness at the heart of our justice system.” These points are critical—meaningful and lasting reform must be rooted in values of fairness and equality, and as importantly, requires seeing more than just a system, and instead, the actual people affected by the system.