AGADEESH NV/EPA/Newscom

AGADEESH NV/EPA/NewscomMillennials are concerned about what’s going on in the world today, and we’re expressing our frustration online and on the ground. In the United States, my generation is helping to put issues like police brutality, gun control, mass incarceration, gender equality, and gay rights, at the center of protests and heated conversations. We’re also focused on what’s happening around the world, attentive to issues of malnutrition and hunger, war, human trafficking, and child marriage. But somehow HIV/AIDS, a disease that intersects with all of these national and international issues, has fallen off the radar.

HIV/AIDS, which 35 years ago stood as the largest epidemic in America, is no longer much of a focus among western youth who are active in social justice. In part, this is because there’s been progress: the creation of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP, a pill which prevents infection in at-risk-negative individuals), Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP, a medication which inhibits transmission after immediate exposure to HIV), and Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), have increased the preventability of transmission and long-term treatment of the disease. For most, HIV/AIDS is no longer a death sentence, and in the last decade, diagnosis has seen a 20% decrease.

But ironically, while new infections overall are in decline, among youth they have actually increased. Around the world today, 11.8 million young people age 15-24 are living with HIV/AIDS and this same demographic accounts for more than half of new infections. In the US, young African American men, primarily LGBT, make up the largest infected population. Globally, young women are most at risk; in Sub- Saharan Africa women age 15-19 make up two thirds of the infected population. And AIDS is still the second highest cause of death globally. Clearly, there’s still cause for concern.

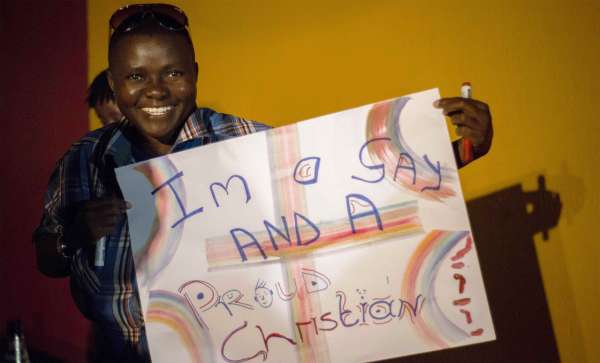

Battling the stigma and the disease

I’m 20 years old, and I have never known a time without HIV/AIDS. Today though, because it is not a “new” problem—and one concentrated within poor communities and communities of color that are already marginalized—we don’t hear much about it in the media. In the western world, because of decreasing prevalence among most populations, and because it no longer stands as a death sentence, most people don’t recognize the disease as an immediate issue.

Despite progress in treating the disease and a decline in new infections among some demographics, HIV/AIDS is not a thing of the past. In this era of “hook up” culture, a lack of awareness, combined with misinformation and lingering stigma, creates the kind of conditions that could lead to new infections. Among young people in the LGBT community, there is still a lot of stigma around the disease. As Wen, a 20-year old openly gay college student and close friend, mentioned in a discussion about HIV, “People are scared to get tested. The disease is seen as a joke, but those diagnosed are shamed.”

In the Global South, millennials know that HIV/AIDS is a risk, but they often lack the privilege and agency many of their western counterparts take for granted. Within much of Sub-Saharan Africa, where young women are eight times as likely to become HIV infected as men, access to condoms and overall condom use remain low. Antiretroviral treatment, as well as PrEP, remains inaccessible for large portions of the population, due to its expense, limited availability, and limited knowledge about the medication. However, the stigma around HIV/AIDS, combined with the prevalence of gender-based violence, exacerbate the problem, as many individuals do not realize, or accept, their risk of exposure and are unable to prevent or treat the infection.

Despite the differences in their lives and nations, the issues that matter to millennials all over the world overlap. But still a lack of communication and shared awareness between the global north and global south (primarily among youth) perpetuates HIV/AIDS in both places. Youth in the global south have more awareness of the disease because it affects large portions of the population, still results in death, and is often represented in the media. But while this day to day awareness of HIV/AIDS normalizes the disease within developing countries, there is a limited dialogue in the global north. This dissociates the disease from developed countries, and bolsters stigma in both hemispheres.

Recognizing HIV/AIDS and inequality go hand-in-hand

My generation can be the one to end the epidemic, but the first step is recognizing that HIV/AIDS is not a public health problem from the past, but an urgent human rights issue that impacts every aspect of a person’s life, especially those already marginalized. The poorest communities, communities of color, LGBT populations, and incarcerated individuals have the highest rates of HIV around the world. Populations that lack technology, access to health care, education, and are found in rural communities, have the least access to medication and contraception. Millennials need to recognize how the issues they already care about—issues like criminalization, poverty, LGBT rights, and race and gender equality—intersect with HIV/AIDS.

Though many millennials still need to become aware of such topics, it’s important to recognize that some are already joining the discussion. This year’s HIV/AIDS conference, which I attended in Durban, South Africa from July 18-22, brought together youth from all around the world and provided an outlet for such conversation. Panels by Black Lives Matter representatives, sex workers, members of the LGBT community, and people from the global north, came together to search for solutions and talk about their ideas and challenges. This conference should stand as a model as these convenings, discussions, and the cooperation of national and grassroots organizations allow millennials of every region to recognize their agency, voice their opinions and experiences, and create change.

Kali Villarosa is a rising junior at Skidmore College, majoring in international affairs with a minor in government and intergroup relations. She is a summer intern in the Ford Foundation’s Civic Engagement and Government program.