When Daryl Bosu talks about Ghana’s Atewa Forest, his hometown pride is palpable. “It is one of the most breathtaking landscapes you’ll ever find in our country. It leaves an enchanting impression for anyone who steps into it,” said the conservationist, who lives close to the forest’s border. “It is very green throughout the year. The trees at the summit sit within the clouds. The water drips down the leaves.”

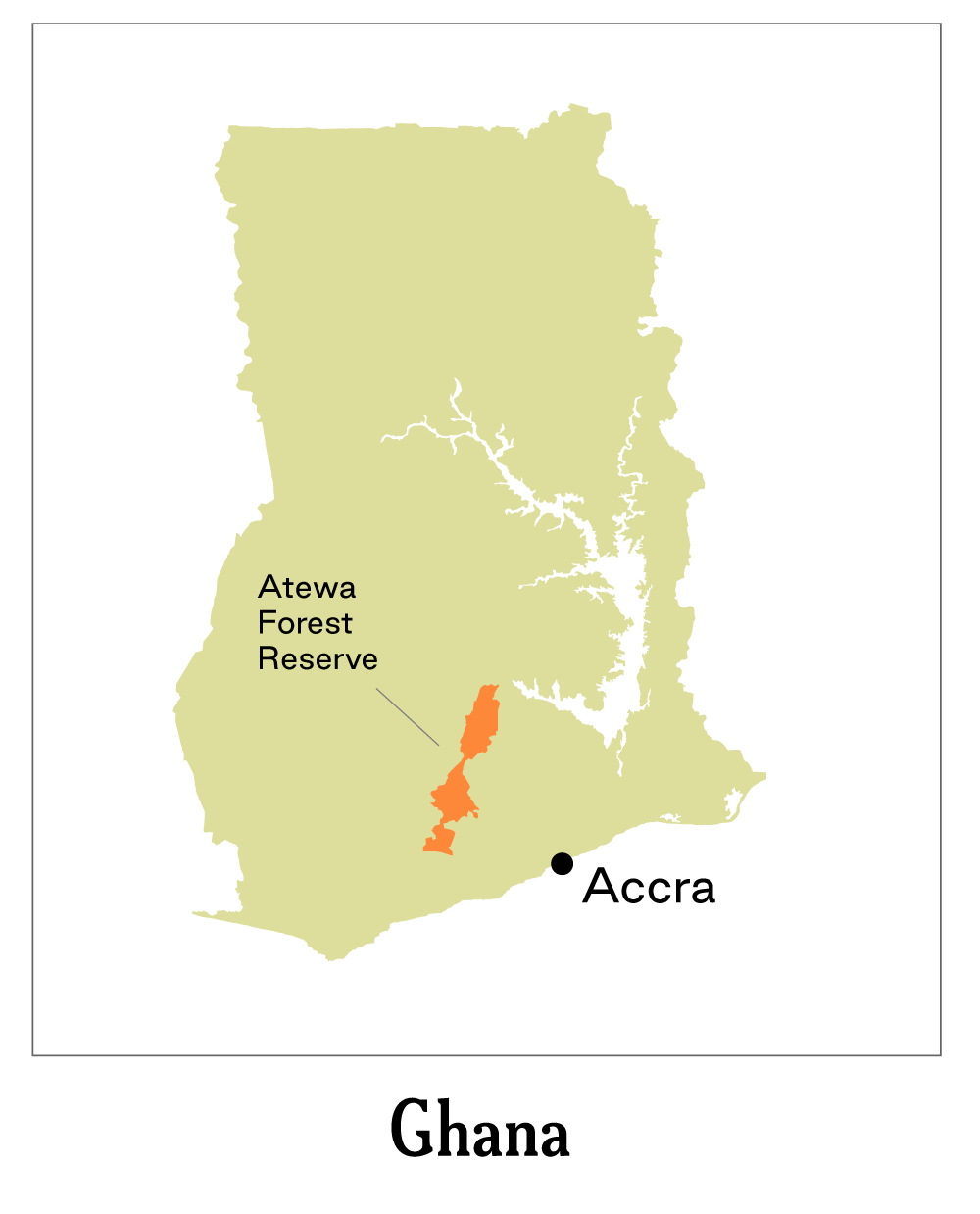

The Atewa Reserve is quite a backyard to have: 25,830 hectares of pristine evergreen forest situated in a mountain range in southeast Ghana. The country’s largest reserve, it is home to more than 100 globally threatened plant, bird, and animal species, including the white-necked rockfowl and Miss Waldron’s red colobus monkey. It is also the source of three major rivers—the Densu, Birim, and Ayensu—that provide water for over 5 million people, including the capital of Accra.

Rainforests like Atewa are one of nature’s best defenses against climate change. They store carbon, stabilize the climate and act as a natural filtration system, keeping the environment healthy not only for the flora and fauna living within these forests but for humanity at large.

The Atewa Forest is now at the center of a heated dispute between the Ghanaian government—which intends to mine its abundant resources as, paradoxically, part of the country’s green energy transition—and conservation advocates like Bosu, who vow to keep them intact.

“The challenges persist, and there are many, but now a lot of people are paying attention,” said Bosu, the deputy national director of A Rocha Ghana, one of the country’s leading conservation nonprofits and a Ford grantee. “They are realizing the dire consequences of the widespread mining across the country and how we’ve taken our natural resources for granted.”

Ghana, like many countries in Africa, has an economy dominated by natural resources, both minerals and fossil fuels. It has a long, fraught history of removing these riches from its land—both by its leaders and colonizing forces—and has struggled with how to harness these resources sustainably to improve the lives of its people. Today, Ghana is the top producer of gold on the continent, with its economy also bolstered by oil and gas production and cocoa farming.

But when it comes to the Atewa Forest, the appeal is in the dirt itself, not what’s buried beneath. The reddish-brown soil that carpets the reserve is full of bauxite, a sedimentary rock that is refined into aluminum. Aluminum is crucial in the production of renewable energy devices and equipment—including solar panels and electric vehicles, two lodestar technologies in the global transition from fossil fuels to clean energy.

However, extracting bauxite from the Atewa Forest means mass deforestation, displacing both rare wildlife and the local communities that use its land for agriculture and food. It means jeopardizing the watershed system that supplies clean water to so many Ghanaians and harming the exact type of ecosystem that serves as a bulwark against climate change, as forests remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and prevent drought. But it also means creating more solar products, which could aid in Ghana’s transition to green energy in time to meet the United Nations’ 2030 sustainable development goals, which Ghana and all member states have pledged to meet. So is this what the expression “between a rock and a hard place” was created for?

Not necessarily, said Bosu. A Rocha Ghana has launched an ambitious, multifaceted campaign to protect the Atewa Forest—a movement it has taken from the region’s local communities to one of Ghana’s highest courts. And Bosu and his team are not alone: Conservation advocates and scholars across the country are urging the government to preserve the forest, arguing that it’s worth more to Ghanaians intact than excavated. But the fight ahead looks long—and there are ominous debts, to the tune of $5 billion, rumbling overhead.

Ghana, like many African nations, is home to a tremendous wealth of natural resources. When managed responsibly, these resources can transform a country’s economy and create prosperous, sustainable societies that benefit all.

One of Africa’s most resource-rich nations, Ghana is no stranger to extraction. It has been a major presence in the country for close to 100 years. Before Ghana became independent in 1957, it was named the Gold Coast, an indication of the riches in its soil. For decades, the country subsisted on its production and exporting of gold, timber, and cocoa.

Then, in 2007, Ghana’s landscape changed overnight when oil was discovered off the coast. Drilling operations sprang up and a golden era, of a different kind, ensued: Ghana halved its poverty rates by 2015 and doubled its economic growth. By 2019, the country was the world’s fastest-growing economy, demonstrating the sort of economic expansion that could be triggered by large-scale natural resource development—even as this came with international calls for the government to protect and sustainably manage its resources more carefully.

But during this time, the benefits of Ghana’s economic boom didn’t always reach its citizens. Despite hopes that the oil windfall would alleviate poverty across the country, deep economic inequality persisted geographically: The south grew more developed and wealthy, while the north, which has lagged behind since the colonial era, remained rural and destitute. According to the UNDP, roughly 65% of the north is multidimensionally poor versus only 27% in the south. The great frustration of Ghana remains unresolved: that a land with such natural wealth could also have such endemic poverty, especially in the communities where its most precious resources were located.

“After Ghana discovered oil, there were explicit promises in terms of how oil revenues would be utilized to address historical inequalities in society. These were not met,” said Abdul-Gafaru Abdulai, associate professor of development politics at the University of Ghana, a Ford grantee. “There are still huge developmental gaps between the northern parts of Ghana and the rest of the country.”

Today, Ghana’s once-robust economy is battling a financial crisis of high inflation, plummeting export revenues, and depreciation of its currency, the cedi. COVID-19 continues to weaken its tourism industry. In 2022, the poverty rate in Ghana rose to an estimated 27%, an increase of 2.2% from the previous year. And since May, there’s been yet another financial shadow over the economy: The country was approved for a $3 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that it will need to repay.

So it’s no wonder that developing bauxite mining in Ghana feels enticing to many, a chance to right the country’s finances after a dispiriting slump. International demand for clean energy technology is rising, with countries around the world investing millions into solar manufacturing. Ghana’s president Nana Akufo-Addo, who co-chairs the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals Advocates committee, has pledged repeatedly to lead the country into a clean, equitable energy transition.

Yet it is hard to reconcile these promises with what’s happening on the ground, especially in the Atewa Forest. Bauxite has been mined for nearly 100 years across the country—as well as in Guinea and Mali—but it’s now happening in areas that were off-limits until recently. Before 2022, the government permitted just 2% of the country’s forests to be mined, with that amount granted only after a lengthy regulatory evaluation. But that year, President Akufo-Addo’s administration passed a regulation stating that he could, in the national interest, allow unlimited mining in all biodiversity-sensitive areas.

“After our 2016 presidential elections, the winning government came in with a mindset to transform Ghana’s economy with a lot of dependence on our bauxite resources,” Bosu said. “They decided to target not only the Atewa Forest, but all other places in the country that have bauxite reserves.”

Mining—whether authorized by the government or done illegally—can have devastating effects on the environment and communities that sustain off the land. From pollution to disease to violent unrest, these impacts can be prevented when extraction takes into account the needs of the people and the planet and prioritizes equal distribution.

In this new, no-holds-barred atmosphere, mining ballooned across Ghana—both large camps authorized by the government and small-scale and illegally run operations called galamsey. Land once devoted to cocoa production swiftly became mining grounds, leaving many farmers without their only source of livelihood. Forest reserves like the Atewa have not been spared. “We have seen an increase of illegal farming activities, logging, and widespread galamsey all over the forest,” Bosu said. “Many communities are of the view that, ‘Well, if the government is going to destroy the forest, why don’t I also take my pound of flesh?’”

Professor Abdulai of the University of Ghana pointed out that restricting mining operations—especially galamsey—can be particularly challenging because of whose pockets they line. “This is a historical problem that governments upon governments have struggled with,” he said. “One reason it’s been so hard to reduce it is because it serves the interest of various power holders in society, including the political class, traditional elites, and some bureaucrats.”

“Galamsey has devastated river bodies and led to the destruction of farmlands,” Bosu added. “We are seeing health-related incidents like kidney failure in local communities who are working at these highly polluted sites and being exposed to polluted rivers and streams.”

The pollution of the Atewa Forest’s intricate watershed system is a top concern for conservationists. The three rivers that originate in the forest carve a spoke-like shape into the rest of the country: The Birim River serves all of eastern Ghana, eventually connecting to another big river called the Pra Basin, which serves the west. The Ayensu River flows from the east and ends up in the central area of the country. And the Densu River feeds the Densu Basin and the Weija Reservoir, which supplies most of Accra with drinkable water.

“The Atewa Forest is a significant hydrological gem,” Bosu said. “It provides water for so many people downstream—and the bauxite substrate in the soil actually contributes to the water recharge process of that entire rock system. Without this forest, more than 5 million people are going to be deprived of water security. That is an issue you don’t want to gloss over.”

Beyond this serious threat to Ghanaians’ water supply, mining the Atewa Forest risks other ecological repercussions. First, deforestation would harm its remarkable biodiversity, which the noted biologist E.O. Wilson called “of exceptional biological importance” in a 2018 letter to President Akufo-Addo urging its protection. It would also mean destabilizing the 40-plus local communities that surround the forest, most of which are farming communities that grow cocoa, oil palm, plantains, and more. Many of them also subsist on forest products, including snails, mushrooms, and medicinal plants. These forest communities have lived in harmony with nature for many years, and their wisdom is urgently needed in the current climate conversation.

More than 40 local communities depend on the Atewa Forest for food, water and their livelihoods. Mining can uproot these communities, pushing them into poverty and exacerbating social and economic inequities.

With interest in mining the forest showing no sign of slowing, A Rocha Ghana has ramped up its efforts to protect the land. In 2020, the group submitted a motion to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to pass a resolution calling for the Ghanaian government to make the forest a national park.

That same year, A Rocha Ghana led a collective of six nonprofits and four individuals in filing a case in Ghana’s High Court to establish the Atewa Reserve as a nationally protected region and overturn plans for bauxite mining. The trial began in February 2023 and is ongoing, which has meant that legal mining cannot proceed until it is resolved.

Their case lays bare an argument rooted in social justice. “Our case hinges on the fact that our constitution guarantees the right to a healthy environment to every Ghanaian, and we believe that destroying this forest will expose Ghanaians to significant environmental hardship,” Bosu adds. “We ask the court to uphold that constitutional right and request the government rehabilitate the degraded areas that have resulted from the illegal exploration done so far.”

A Rocha Ghana has also taken to social media with its conservation campaign, appealing to international audiences with the release of “Atewa Till Eternity,” a catchy rap song with pro-conservation lyrics and lush footage of the forest.

Concurrently, the group partnered with the local communities surrounding the forest to design strategies to help them adapt to the changing circumstances. This includes establishing community monitoring units, which helps residents report illegal activities to A Rocha Ghana, who in turn alert the police and urge officials to take action.

A Rocha Ghana also researched a path toward green development for the Atewa Forest, which proposes opportunities for sustainable energy and ecotourism over extractivism. “This is to help the government appreciate the green development opportunities that they could benefit from if they followed a sustainability pathway,” said Bosu. “There are better routes available for everyone. And there is definitely hope.”

A Rocha Ghana partners with Atewa’s local communities to advocate for their needs, amplify their voices, and ensure they are part of the solution to protect the forest now and for generations to come.

Despite the many risks of mining the Atewa Forest, the Ghanaian government continues to encourage extraction efforts. Some of this nods back to campaign promises made by President Akufo-Addo, whose hometown is near the forest: He pledged to open a bauxite mine there and create new jobs. But there is also intense pressure coming from international partners—not just the IMF and its $3 billion tab, but from the Chinese government, who, in 2018, provided Ghana with $2 billion for infrastructure development in exchange for access to 5% of the country’s bauxite reserves. China currently dominates global solar supply chains, and it operates mines in other parts of Ghana, but this new deal puts extra onus on bauxite because the Ghanaian government has said it plans to pay back the loan with the sale of it.

However, this plan is inherently flawed, according to Benjamin Boakye, executive director of the Africa Centre for Energy Policy, an Accra-based research and advocacy nonprofit and Ford grantee. Before the agreement was signed, the center analyzed the $2 billion Chinese deal and discouraged the government from moving forward because it found Ghana’s bauxite wasn’t as lucrative as projected.

“In our analysis, we showed the government that they were not going to make enough money from the bauxite extracted to pay back a $2 billion debt,” Boakye said. “They were going to have to find that money somewhere else in the budget, which could hurt Ghanaians. The other benefits Ghana was getting from the Atewa Forest were much higher than what the government was seeking to gain by exploiting bauxite.”

Bosu agrees. “The Atewa Forest has less than 20% of Ghana’s bauxite reserves, and our research shows that the bauxite deposit there is low grade. It’s not really of commercial value,” he said. “Our position has always been that, yes, we have bauxite, so let’s take advantage of it—but let’s do it properly, making sure environmental and social protections are in place, and recognizing that certain places in this country are no-go areas.”

Despite their opposition and obstacles, the advocates for the Atewa Forest’s preservation remain undeterred. Bosu, for one, is resolute—and he does not lose sight of why.

“The Atewa Forest was set up in honor of one of our traditional leaders, Nana Sir Ofori Atta I, who was a very strong advocate for land rights and protection,” Bosu said. “He said that we do not own the land, we borrow it from our children and our grandchildren. We need to make sure we leave it as it is for them.”