For generations, the United States of America has been built on a pact: secure a job, commit to it, and ensure a stable life. Yet for millions of workers, this promise is dissolving.

Across every sector, jobs are becoming increasingly precarious. Gig work, temporary positions, and subcontracted roles are replacing traditional employment, leaving workers with unpredictable incomes, erratic schedules, and a lack of benefits. This instability breeds anxiety, disrupts families, and creates a sense of expendability, ultimately destabilizing entire communities and creating a race to the bottom economy.

This rise of precarious work is no accident. Decades of policies prioritizing corporate profits over worker protections have eroded job security and weakened worker power. By design, this uncertainty leaves workers vulnerable and less likely to demand their rights, individually and collectively.

But a new wave of worker activism is rising to meet this challenge. Nationwide, workers are organizing across industries and state lines; forming unions, building power in new coalitions, and pushing for bold reforms that protect workers and not just corporate interests. Above all, they’re proving that in this economy, isolation is the enemy and collective power is the solution.

Among those leading the fight for a more just economy are Ford’s grantee partners. Their stories are diverse: an app delivery driver organizing for fair wages and protections, a fashion model combating exploitative practices, a warehouse worker demanding safe conditions, and a solar industry temp worker advocating for a sustainable planet and employment. Their experiences are just a sample of what workplaces look like across the country, and the kind of innovative advocacy that is being undertaken nationwide. These individuals, and the organizations they advocate alongside, are challenging precarious work and sharing their hard-won progress towards a future where all workers have a voice and a chance to thrive. Here are some of their stories.

App-Based Delivery Drivers and the Road to Justice

The Worker’s Justice Project

As a driver for food delivery apps, William Medina navigates the treacherous landscape of New York City every day. Since moving from Colombia with his family six years ago, he has worked for several of these companies, facing harsh weather, dangerous streets, and significant threats of violence and theft.

“I’ve worked in -25 degree weather, which is almost unbearable to spend over four hours in. In the heat, we suffer a lot of burns, skin irritation, and dehydration,” he said. “I’ve had lots of accidents on the bikes I had. Once, my motorcycle was stolen at gunpoint. It took me a long time to save that money and in five minutes, I lost it all.”

Medina’s experience is a stark reminder of the challenges faced by thousands of delivery workers, or “deliveristas,” who power the city’s booming food delivery industry. Classified as independent contractors, they lack basic worker rights and are at the mercy of opaque algorithms that control their pay, hours, and even access to tips, leading to unrelenting pressure to perform deliveries without regard to safety conditions. As a result, app delivery work is now the most lethal occupation in New York City, and according to research one of the most dangerous overall.

But Medina does not only deliver food—he’s delivering change to his industry. As a labor organizer with the Worker’s Justice Project (WJP), he’s part of a movement uniting delivery workers across ethnic and cultural backgrounds to demand better working conditions.

WJP is a worker center, which is a nonprofit that aims to organize and train workers who are not yet members of traditional unions and usually focuses on supporting low-wage workers. WJP organizes workers and fights to raise workplace protections and wages in the app-based delivery, construction, and house-cleaning industries. The group is active in supporting workers who have been on the frontlines after citywide disasters, including Hurricane Sandy and COVID-19—crises that affected all New Yorkers, yet left independent and gig workers particularly vulnerable.

The movement gained momentum in 2020 with the formation of Worker’s Justice Project’s Los Deliveristas Unidos organizing campaign, which is led primarily by Indigenous Guatemalan and Mexican workers. They organized to address critical needs for workers including street safety, access to bathrooms, and pay transparency. “Our power is in our unity,” emphasized Medina, who actively connects with deliveristas from diverse cultural backgrounds who experience similar struggles. This resulted in building community and solidarity with workers from West Africa, South Asia and particularly Bangladesh, who shared similar concerns.

“We don’t want a robot to rate us. We don’t want the algorithm to retaliate against workers. There needs to be a balancing point.”

William Medina

WJP combines direct support, like providing bike repair services, with broader advocacy for systemic change. Their research and reports, including “Essential, but Unprotected,” have been instrumental in raising awareness about the challenges faced by delivery workers and fostering collaboration among diverse groups.

Their strategy for short- and long-term change is working. In a landmark win, WJP helped secure a minimum wage increase for app-based delivery workers in New York City, raising their pay to $19.56 per hour before tips, up from just $5.39 before.

“We are making sure workers who are usually invisibilized are finally heard, seen, recognized, and respected,” said Ligia Guallpa, executive director and cofounder of Worker’s Justice Project.

Beyond fair wages, WJP advocates for greater transparency in payment systems and helps workers resolve disputes with app companies, including around unpaid wages or unfair deactivations of their gig platform accounts.

They have also successfully pushed for the creation of “Deliveristas Hubs” — safe spaces for workers to rest, organize with other workers, and recharge their bikes — and partnered with city officials to improve bike lane infrastructure and traffic safety measures. The first hub will open in 2025 at City Hall Park in Downtown Manhattan, an area with one of the highest uses of app delivery in the city.

While delivery apps and their algorithms are here to stay, Medina stresses the need for balance. Workers deserve fair treatment, not just automated management. “We don’t want a robot to rate us,” he says, advocating for a system that values human dignity alongside efficiency.

“We don’t want the algorithm to retaliate against workers,” he said. “There needs to be a balancing point.”

Runways to Collective Action – Fashion Workers Demand Dignity

The Model Alliance

Esmeralda Seay-Reynolds began modeling for some of the top fashion designers and labels in the world at age 15, a lifestyle she called “a Cinderella fantasy”—except for the abuse and exploitation she regularly faced behind the scenes.

“Modeling means you have these blips of extreme situations—whether they’re really incredible, like you’re the face on a magazine, or really awful, and you’re being physically abused by a photographer or psychologically abused by your agent, or you’ve been financially stolen from,” said Seay-Reynolds. “It’s supposed to be the best thing that could ever happen to you, and it feels terrible.”

Seay-Reynolds is a member of the worker council for the Model Alliance, a New York nonprofit that advances labor rights in the fashion industry. Founded in 2012 by labor activist and former model Sara Ziff, the organization has achieved significant milestones, from establishing child labor protections in the modeling industry to creating the first and only fashion worker support line. Notably, they also played a crucial role in the passage of the 2022 the Adult Survivors Act, enabling survivors of sexual assault to file lawsuits beyond the statute of limitations and resulting in over 3,000 suits filed.

“It’s supposed to be the best thing that could ever happen to you, and it feels terrible.”

Esmeralda Seay-Reynolds

Ziff and Seay-Reynolds’ work often highlights the systemic power imbalance in the trillion-dollar global fashion industry, with often young models facing regular exploitation from older agents and photographers. This is exacerbated by the lack of regulation for modeling agencies, which hold significant control over models’ careers and finances. Seay-Reynolds recounts instances where this lack of oversight led to dangerous situations for her, including being sent to a known sexual predator’s apartment on a “go-see” and being pressured into a risky photo shoot in Iceland where the photographer demanded she crawl into caves and jump over ravines, all in skimpy garments.

“Since its inception, the industry has been a backwater for workers’ rights, rife with various abuses that are basically considered the price of admission. Yet the perception of glamor contributes to a distinct lack of sympathy for models, as if what we do is not real work,” said Ziff, who made a documentary about her modeling career, Picture Me, in 2009. “I think this is the case for many jobs that are devalued because of their association with femininity. So we have a lot of structural sexism to overcome.”

Financial precarity is another issue, given models are typically contractually designated as independent contractors represented by modeling agencies; these unlicensed, unregulated companies exert enormous control over the teenage girls in their employ, from asking them to sign exclusive, multi-year, auto-renewing contracts to holding power of attorney over them. This allows the agency to book the models’ jobs, negotiate their rates, control their payments, give third parties permission to use their image, and deduct expenses without explanation (Seay-Reynolds was once paid only $130 for six weeks of high-profile work). Models are largely unprotected outside of the terms of their individual contracts, which tend to be stacked heavily to the advantage of the modeling agencies, and results in a wholesale lack of transparency, accountability, and autonomy.

To combat these problems, the Model Alliance is demanding protections for fashion workers, including zero-tolerance policies for abuse, autonomy to decline jobs, increased transparency and accountability within agencies, and establishment of a fiduciary duty for agencies to act in their talents’ best interests. With the accelerating use of technology across society, the Model Alliance is also calling for protections against the misuse of AI by requiring that agencies and brands get clear, written consent for the use of a model’s digital replica.

Ziff emphasizes the importance of labor solidarity across the fashion industry. “Across the board, whether you’re walking down a runway in New York or you’re in a factory in Bangladesh, this is an industry that is built largely on the backs of young women and girls who are trying to have a voice in their work.”

Boxed Out No Longer: Warehouse Workers Demand Safe Working Conditions

For the Many

America’s ecommerce market is booming, projected to surpass $1.3 trillion in sales in 2024. This surge in online shopping, where a world of products are instantly accessible by computers and smartphones, has reshaped the retail landscape. However, this convenience often masks a harsh reality for the people who make it possible: warehouse workers. The enormous scale of online retail, driven by the need for rapid order fulfillment and ever-faster delivery times, puts immense pressure on millions of warehouse workers, particularly those employed by giants like Amazon, Walmart and Target, among others. These workers represent the hidden human cost of the ecommerce revolution.

These companies are known for having hundreds of millions of customers, but there are other numbers that don’t get as much publicity. Some of these companies have an alleged annual employee turnover rate of 150% and nearly 50% of warehouse workers are injured during peak sales rushes.

The business processes of e-commerce giants “try to turn people into robots and maximize their work efficiency—and if people can’t keep up, they’ll be replaced,” said Jonathan Bix, executive director and cofounder of For the Many, an upstate New York nonprofit that organizes workers and advocates for labor-friendly legislation. “You see the difficulties of that in these companies’ very, very high turnover rates.”

In recent years, America’s warehouse workers have reported numerous harrowing labor conditions, including increased surveillance and excessive productivity requirements that can make even going to the restroom challenging. In response, workers are increasingly organizing and collectivizing, whether in unions or workers councils.

Keith Williams, a warehouse worker and labor organizer in New York, said the push to make this type of work safe and sustainable has been met with resistance from management, but solidarity is growing steadily among his colleagues.

“Change is wanted and needed,” he said. “We see the wins and we see the progress, and that’s what keeps us going. We are letting these companies know that we’re not going to go away.”

One of Williams’ chief motivations is the lack of safety measures, with management often disregarding injuries as annoyances. He says these companies see you as “a better employee if you can push past being tired and hurt to get back out there.”

Williams has suffered two injuries on the job, including having a desk fall onto his neck in a dark equipment trailer, which he asserts would have been avoidable with proper safety precautions in place. He said management discouraged him from pursuing worker’s comp, but he did so regardless, and has experienced numerous complications in receiving it. In the interim, he has also suffered hand and nerve damage related to his injury.

“We see the wins and we see the progress, and that’s what keeps us going. We are letting these companies know that we’re not going to go away.”

Keith Williams

Bix contends that the size of major warehouse and ecommerce companies stacks the deck against workers, noting that ecommerce companies must be held accountable to their legal obligation to participate in collective bargaining. He also noted that antitrust rules remain outdated. “We must update our anti-monopoly laws to be able to keep up with these new corporations that are basically entire nation-states and the size of entire economies by themselves,” he said. “These kinds of companies are not going to self-regulate.”

Williams can see, meanwhile, that worker power is gaining traction among his warehouse colleagues. They have already improved conditions by learning about their rights, securing time off to vote, negotiating for employees to bring a witness when they meet with management, and ensuring that essential training and safety information is posted in Spanish for its majority Latino workforce.

“We are letting people know that they actually have rights, that they’re still human once they’re walking into that building,” said Williams. “Knowing my rights has made my job more secure, because management knows that I know my rights.”

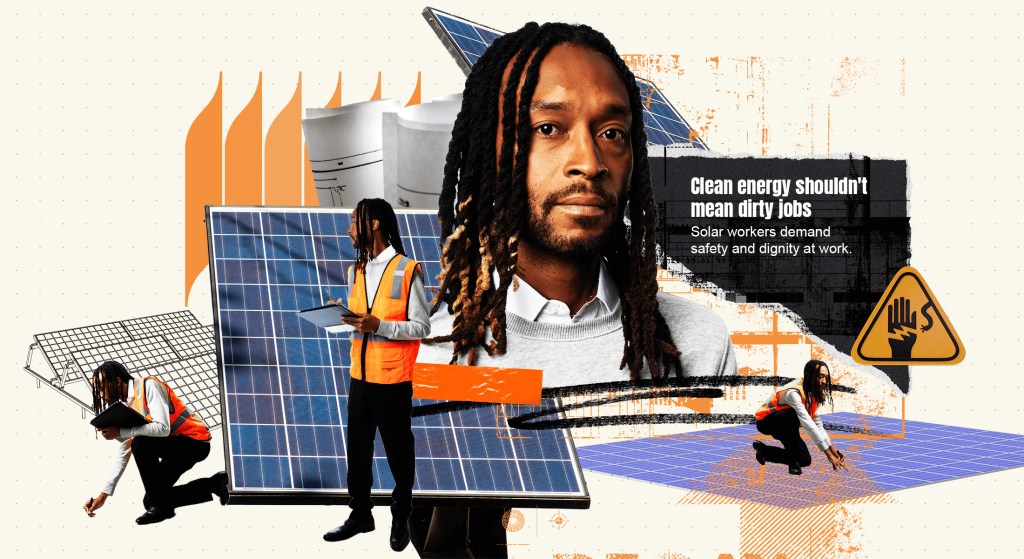

Fixing the Dark Side of the Solar Industry

The Green Workers Alliance

The sustainability of our planet depends on transitioning to clean energy sources, especially solar power. But how sustainable are working conditions for the people building this crucial technology?

Not very, said DaShawn Beaulieu, an electrical quality control representative for a solar energy corporation and an activist with the Green Workers Alliance, a nonprofit that supports workers in the clean energy field. He works at solar construction sites—and said it’s brutal, physical work where safety can quickly fall by the wayside.

“There’s a tremendous amount of opportunity within solar, but it’s very rough work and there’s always a threat of imminent danger. It’s a free-for-all with no protection; if someone gets injured at work, there’s nobody to call,” said Beaulieu. “To eliminate a bunch of that liability, the companies always go through a temp agency.”

Temp agencies are the backbone of the rapidly growing solar industry, and many other industries, too. They hire workers on individual projects with no assurance of future work, and use their intermediary role to deprive workers of the proper safety training and reasonable hours they might get from direct employment. Temp-hired workers’ wages are often more opaque, with a cut of them going directly to the agency. Despite these subpar conditions, temp workers often find limited options beyond them: This employment model disproportionately impacts immigrants, formerly incarcerated individuals, and people with disabilities.

“A lot of these people fear retaliation, and they’re not educated in regards to the legal aspect. But managers can’t fire you for complaining.”

DaShawn Beaulieu

What’s worse, exploiting workers undermines the entire global transition to green energy, because “you can’t do it on the backs of bad jobs,” says Matthew Mayers, executive director of the Green Workers Alliance. “It’s the wrong thing to do and, also, people won’t take the jobs.”

The Green Workers Alliance organizes solar and wind workers and advocates for policies that simultaneously fight climate change and increase the number of jobs with fair labor conditions. The group often collaborates with unions and connects workers to outside lawyers and labor experts if they have experienced wage theft or feel they’ve been unjustly terminated, have experienced sexual harassment, or are uncertain about claiming worker’s comp for an injury. “Sometimes folks will be scared or wary of applying for workers’ comp because they’re like, ‘I don’t want to not get hired again on a project,’” said Mayers.

Sheila Maddali, executive director of Grassroots Law & Organizing for Workers (GLOW), a racial and economic justice organization, argues that the temp work model, a $146 billion industry, allows companies to exploit workers by creating a power imbalance. This “fissuring” of the employer-worker relationship lets companies avoid accountability for issues like wage theft and discrimination, as they can simply deflect blame to the temp agency. GLOW believes a widely adopted Temp Worker Bill of Rights is essential to eliminate pay disparities and increase oversight of temporary staffing agencies. These kinds of protections have already been passed in New Jersey and Illinois. According to Maddali, temp worker organizing is also an irreducible component to strengthening protections on job sites.

GLOW has found that a direct hire and a temp worker working side-by-side often live different realities. “On average, the temp worker made $4 less an hour, and workplace injuries and fatalities were about four times higher for them because they were not getting safety training or personal protective equipment,” Maddali added.

Knowing these unfair conditions, Green Workers Alliance’s overarching mission is to foster collective power and better oversight for more solar and wind workers. Beaulieu knows that achieving these goals will require educating his colleagues about their rights —at every level of the solar workers’ employee structure. “A lot of these people fear retaliation, and they’re not educated in regards to the legal aspect. But managers can’t fire you for complaining,” he said.

Mayers is optimistic that, much like the success of worker struggles in the past, the subpar labor conditions of green workers can be reversed, too. “There are two paths forward. There’s continuing on this race-to-the-bottom path, where work in this industry and others is being done by folks who are taken advantage of as long as the companies can get away with it,” he said. “And the other path is to come up with a high-road model: helping people with issues on the job, building worker power. That’s the start to transforming this industry.”

Ford Foundation’s Future of Work(ers) program recognizes that building worker power across all sectors, industries and demographics is essential to combatting precarity. By amplifying the voices of workers, we know that we can address the green energy transition, gender based violence and harassment, industrial surveillance and algorithmic harm. When workers lead, a just economy that fosters just communities and a just future for everyone is possible.