On the day before the start of the new school year, New York City schools chancellor Carmen Fariña announced the Free School Lunch for All initiative, under which every child enrolled in New York City public schools—that’s all 1.1 million children, from pre-K through 12th grade—will be able to eat lunch at school for no cost. We cheered the announcement, which came as the culmination of a multiyear effort led by Community Food Advocates, a grantee of the Ford Foundation’s Good Neighbor Committee.

Why free lunch for all?

The majority of New York City’s public school students are poor; an astonishing 75 percent (780,000 children) were already eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. School lunch is the only nutritious meal many of them eat all day. But eating free lunch had stigma, and so despite their need, one in three eligible students skipped lunch to avoid the shame.

Universal free school lunch is a simple but radical idea. It removes stigma, improves children’s health and education, and helps low-income families make ends meet. Because it is one system, it also simplifies administrative processes, allowing schools, principals, and teachers to focus on teaching.

Other large cities, including Chicago, Dallas, and Boston, already serve universal free meals. But New York City has the largest school district in the country, making its move a national model that might encourage other districts to change their own policies.

Building the will for change

While the idea of universal free meals seems like a no-brainer, it wasn’t easy to achieve. Advocates needed to build political will for policy change, which was complicated by competing public priorities and by concerns over cost and administrative issues. A key factor in the program’s success was an improvement in state income matching data, which provides the basis for the city to calculate federal and state meal reimbursements. This meant that because the vast majority of New York City students already qualify for free lunch, it was possible to expand free meals to all students at no cost.

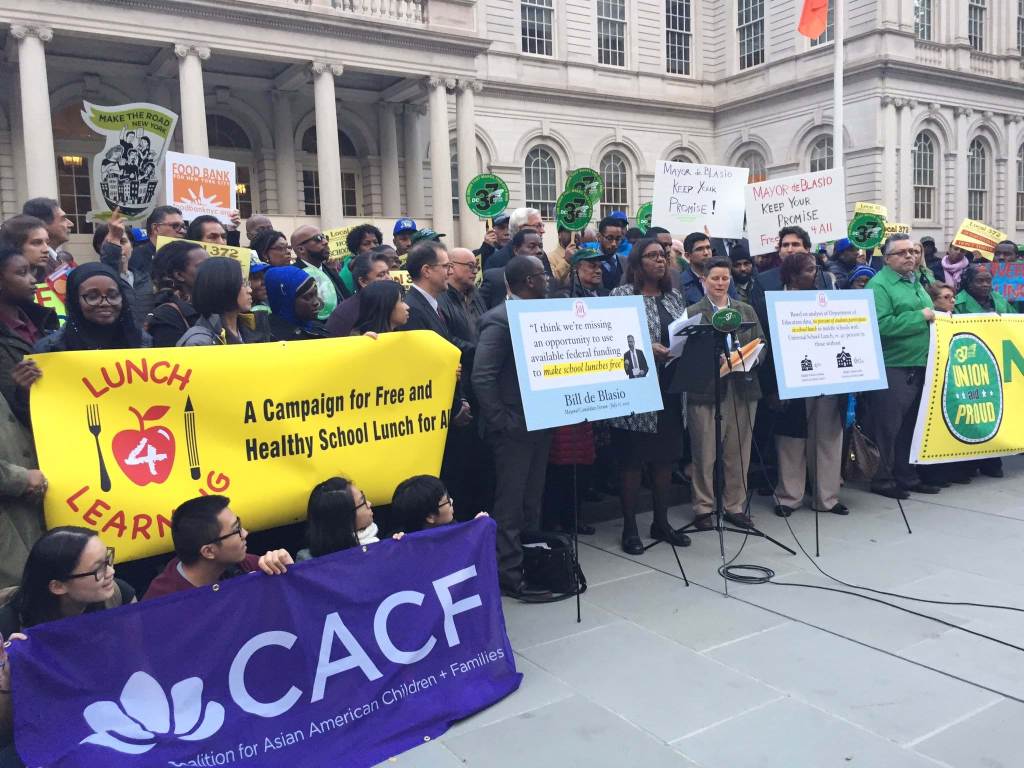

Success was also made possible by the active engagement and advocacy of the many community partners who came together under the Lunch 4 Learning campaign, spearheaded by Community Food Advocates. The campaign’s coalition included students, parents, educators, school-based unions, medical professionals, and public officials. Celebrity chefs, including Rachael Ray, lent star power. But at the campaign’s heart were student and parent groups, who brought their passion and personal stories to the effort. They prepared testimony, met with elected officials, and ran social media campaigns. One effective Twitter campaign asked students, teachers, and parents to share selfies that explained why universal free meals were important to them. And so the policy victory is now their victory—empowering the community and building infrastructure for future civic activism.

Making grants in our own backyard

Ford’s support of this extraordinary effort was a collaboration between the two of us, colleagues from different areas of the foundation: Janna is department coordinator in Ford’s hedge fund investments area, and Amy is senior program officer in our Civic Engagement and Government (CEG) program. Janna is also a member of Ford’s Good Neighbor Committee (GNC), which focuses on grantmaking in our immediate community (the neighborhood surrounding the foundation’s office in New York City) and offers staff whose role is not primarily related to grantmaking the opportunity to participate more directly in that essential part of the foundation’s work.

Supporting Community Food Advocates was a perfect collaboration between GNC and CEG: The organization works locally to increase equity and improve the lives of New Yorkers—and their work aligns with CEG’s strategy of supporting powerful civic engagement by the people who are most impacted by policies as the route to progressive change.

Ford’s grant to Community Food Advocates for the Lunch 4 Learning campaign shows how a small investment can support big change. It’s also an example of how internal collaboration can support integrated campaigns on the ground—how working together can lead to broader and more impactful change.