©Bagus Indahono/Corbis

©Bagus Indahono/CorbisIt’s evening in Paris, and we’re walking together across the busy Place du Trocadéro, with the Eiffel Tower lit up on the skyline behind us: Three women, normally worlds apart, brought together by the UN climate talks and the #PaddletoParis campaign. Mina Setra is an indigenous Dayak from the forests of Borneo in Indonesia. With us is Diana Rios, an Ashaninka, from a small Amazonian community in Peru. Me, I’m white, European.

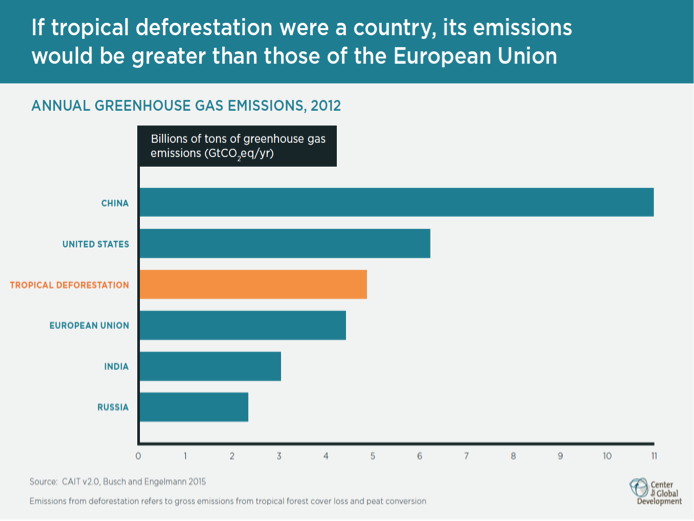

I’ve come to Paris to see whether governments will agree to cap their carbon pollution. Emissions into the atmosphere from burning oil and coal are heating the planet. But what many don’t know is that after oil and coal, the greatest source of carbon pollution is from clearing forests. If tropical deforestation were a country, its emissions would be greater than those of Europe.

I ask Mina why she is here. “That Eiffel Tower is strangely beautiful,” she says, pointing to the iconic landmark. “My village in Indonesia was also beautiful. It had land and forests. We lived off the forest fruits. But we lost it all. It’s now gone, in smoke and big palm oil.” On a clear night in Paris, it’s easy to forget Indonesia’s forests have been burning for several months now, swathing its cities and airports in haze. Vast rainforests burnt, cut down, and cleared for industrial plantations.

These communities face not only loss of land and livelihood, but also violence and assassination. “We still have a lot of forest where I live,” Diana explains. “I’ve come to speak about my community there, Saweto, and about my father as well as my uncle, Edwin Chota. They were murdered just over a year ago, defending our forests and land.”

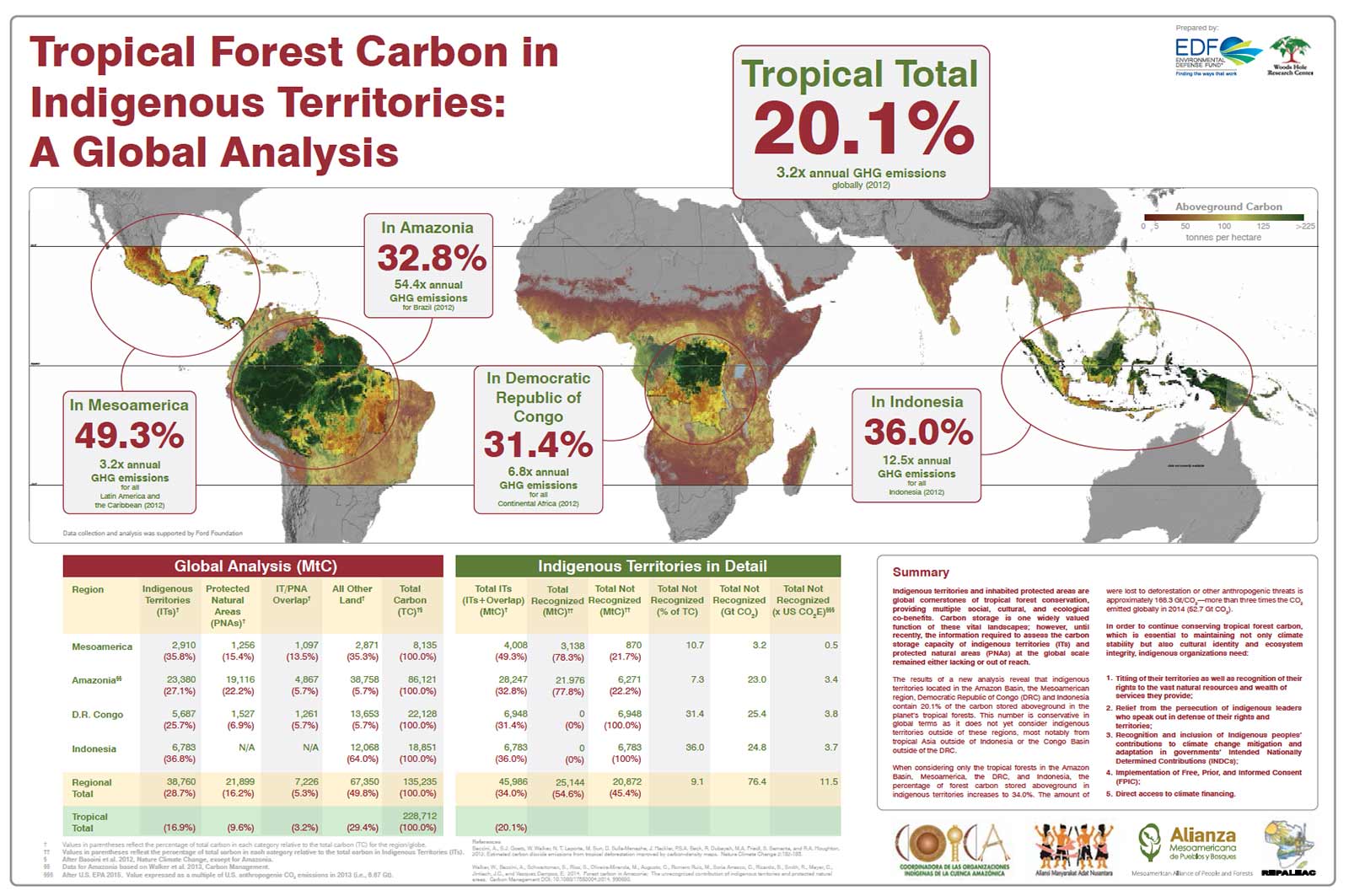

Diana has travelled from Saweto, a small cluster of wooden and thatched houses hidden away in the Amazon. She is one of many indigenous leaders who have “paddled to Paris.” It takes several days by canoe to get to the nearest town, then another 10 hours by road to the capital, and an even longer flight to Paris. Across the tropical world there are millions of indigenous peoples living in far-away communities like Saweto. Hundreds of them, like Mina and Diana, have come here because they too want a say in the climate talks. Together they are protecting a fifth of the world’s last standing tropical forests. Their forest stewardship stops 168.3 gigatons of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) from entering the atmosphere—more than three times the world’s total carbon pollution last year.

On Monday, heads of state gathered here in Paris to announce the reductions their countries will make in the amount of GtCO2 they emit. On the same day, a group of grassroots networks—the Indonesian Alliance of Indigenous Peoples (AMAN), the Amazon Coordination of Indigenous Organizations (COICA), and the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests (AMPB)—launched a new map based on the latest satellite imagery data. The map tells a clear story. Where communities have secured rights to their forests and land, less forest is lost than anywhere else. The bottom line: Securing rights is a way to combat climate change.

Without secure rights, indigenous communities and their forests are vulnerable to industrial logging, plantation, and mining concessions. More than half the world’s land is under community management, but less than a fifth has formal legal recognition.

It doesn’t cost much to title a piece of land and recognize indigenous peoples’ rights. But as Mina and Diana know all too well, protecting their forests doesn’t come cheap. Last year two environmental defenders were killed every two weeks in the struggle over land and natural resources. Diana’s father, Jorge Rios, and her uncle, Edwin Chota, were among them. There are many others: Idrina Pelani was killed near an oil palm plantation in Indonesia. Rigoberto Lima Choc was shot dead in Guatemala. Luis Marcía Ventura killed in Honduras. Chai Bunthonglek in Thailand. Eusébio Ka’apor in Brazil. The list goes on.

It’s not just forests that are burning. Our unsustainable consumption of fossil fuels and other resources, like palm oil (ubiquitous in many products we buy from our local grocery stores, including margarine, ice cream, and peanut butter), is fanning a huge fire of inequality and disparity in the global patterns of resource production. Although 65 percent of the world’s land is inhabited and managed by indigenous peoples and local communities under customary (traditional) systems, they only have secure, formal rights to 18 percent of the world’s land. This unequal gap drives not just climate change, but also conflict and cultural extinction.

Listening to Mina and Diana talk I find it easier to see how climate change and inequality are two sides of the same problem, and to understand why hundreds of indigenous peoples have travelled such huge distances to Paris. They are here to remind us that climate change is not only about oil and coal. Forests are also crucial. And it’s not just about carbon statistics. It’s about us doing our part, wherever we live, whoever we are.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.