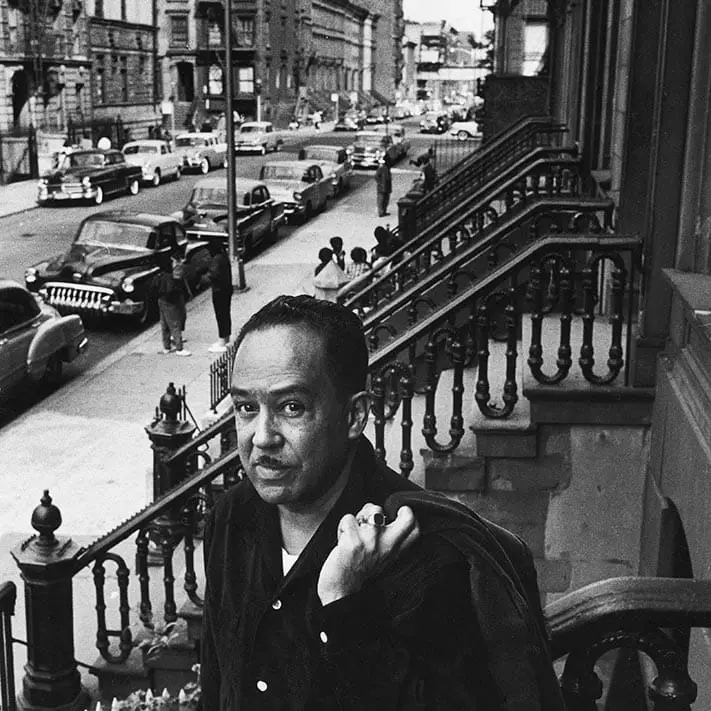

Paul Taylor/Getty Images

Paul Taylor/Getty ImagesLet America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

(It never was America to me.)

– Langston Hughes, “Let America Be America Again,” 1936

In moments of uncertainty, we often return to familiar touchstones. For me, one such anchor of comfort and clarity is the poetry of Langston Hughes, icon of the Harlem Renaissance.

During recent weeks, I’ve found myself ruminating on Hughes’s “Let America Be America Again,” especially its astonishing opening stanzas. In these 10 lines, Hughes evokes the power of the American promise, coupled with the pain of indignity and inequality. He speaks to the complex mix of rage and hope, of anxiety and optimism, that characterizes the black experience in America—and that I would argue has characterized the experience of many Americans at some point, white, brown, black, indigenous, and immigrant.

Over the past year, it has become clear that the noxious swill of rage and anxiety remains as potent as ever. Regardless of which side of the US election each of us was on, we all find ourselves living with a public discourse that has become increasingly callous, contemptuous, and polarizing.

So, as we launch ourselves into a new year, I find myself reflecting on where we go from here—how we counterbalance anger and hopelessness with radical hope and optimism, and how we create, in Hughes’s perfectly chosen words, “that great strong land of love” and dignity for all.

Two reactions to our current moment

Hughes’s poem captures a tension I’ve noticed in many of my daily interactions over the past several weeks, in all kinds of settings and among all kinds of people, including myself: a tension between a sense that our times are dangerously unprecedented and a sense that while dangerous, they are all too familiar.

On the one hand, many of us feel that the world has been turned upside down. To read the headlines is to see an unfamiliar landscape in which several unsettling trends have converged. The proliferation of fake news and the prevalence of brazen falsehoods on air and online are undermining faith in basic facts. The burgeoning democratic institutions that captured the imagination of Alexis de Tocqueville nearly 200 years ago—our civil society, our free press, our universities—are increasingly beleaguered and besieged. Rising hate speech and violence across the country has rightfully frightened many people. All this constitutes an assault on what we thought were well-established societal norms.

On the other hand, some of us look to history and recognize that our current moment is not without precedent. To me, one clear parallel is America’s post-Reconstruction era in the South, when some Americans worked to roll back and repeal the hard-won voting rights and educational and economic opportunities that brought freedom and dignity to the lives of so many of their fellow citizens.

Indeed, racism, sexism, xenophobia, and all kinds of othering are not new. Identity politics has always been a part of American life. Our founding fathers codified identity politics into our earliest documents, valuing the voices and contributions of white men above all others: Women were denied the right to vote; enslaved African Americans counted as three-fifths of a person; indigenous peoples were exploited and marginalized. And throughout our history, waves of immigrants from Europe and elsewhere were initially met with suspicion and often discrimination. It’s important to remember that over the course of our long, messy march toward justice, women and men—not just our predecessors, but we, the people, of every generation—have endured prejudice and persecution. We have seen it with our own eyes, and lived it in our own lives.

I’ll never forget coming of age as a gay man in the 1980s—watching AIDS ravage our community as politicians stayed silent. I’ll never forget the brutality of apartheid, and how our own American government condemned Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and the other freedom fighters seeking to end that unconscionable regime. I’ll never forget watching as the marches and protests unfolded in Ferguson in August 2014, or standing with John Lewis on the Edmund Pettus Bridge a few months later, awestruck as he recounted the bloody Sunday in Selma 50 years earlier.

America’s rich and inspiring history has taught us that progress is not linear. As the dazzling Zadie Smith recently wrote, “Progress is never permanent, will always be threatened, must be redoubled, restated, and reimagined if it is to survive.” So while these twin reactions—the sense that our moment is either unprecedented or has clear precedent—may seem at odds, they actually reaffirm a deeper understanding of the persistence of injustice in our world. They also remind us of the strength we must continue to find within ourselves to persevere and fight for our democratic institutions and ideals.

Confronting divisions, affirming dignity

Over the past three years, I’ve written about the ways inequality creates and exacerbates divisions. These include divisions of class, race, gender, identity, and ability, as well as differences in how we make sense of injustice in our lives.

There is no better illustration of this last category than the political binary of an election year, when our two-party system induces us to spend months defining our collective future in terms of us versus them, this stark choice versus that one. This rhetoric reinforces the notion of zero-sum outcomes, and encourages us to believe that the gains of one happen at the expense of another.

We must resist this impulse. It is easy to lose sight of what we have in common, but the fact is that all of us share a fundamental human aspiration: to live in dignity. This is true no matter what we look like, where we live, how we worship, who we love, or what our abilities are. Whether by holding a decent-paying job, having agency in the decisions that affect us, or freely expressing our thoughts and creativity, we spend our lives in pursuit of dignity for ourselves and our families. Recognizing this universal quest for dignity is a prerequisite for any meaningful work toward social justice.

I am not suggesting that dignity is guaranteed. There are people and systems that seek to rob people of their innate dignity. They advance narratives that pit communities against one another—that permit some to falsely claim that the only way to ensure dignity for yourself is to strip it from others.

Of course, the dignity of one person does not preclude that of another. We can lift a poor Latina out of poverty and save a rural white man’s factory job. We can fight to protect black lives and the lives of the law enforcement officers who protect us. We can hold up a beacon of light for the “tempest-tost” refugees who seek safety and opportunity on our shores, and feel safe and secure in our neighborhoods and gathering places.

I’m not simply saying that we can do all these things; I’m saying we must.

Our current context demands that we question our assumptions and expand our understanding of who is vulnerable and excluded. If inequality fuels the fault lines of division, then our shared pursuit of dignity must help bridge the gaps. To borrow a phrase from the brilliant artist Lilla Watson, our liberation is bound up together.

The path forward:“America will be!”

It might be tempting to ignore or abandon the mutual obligation that ties us together, to embrace a kind of nihilism of indifference or, worse, to retreat into anxiety or rage. But we can choose a better path forward. With history as our guide, we can follow a path of hope—radical hope.

For Langston Hughes, born in 1902, the gap between America’s promise and its practices was wide. The great-grandchild of slaves on one side and slaveholders on the other—the child of educators and organizers—Hughes lived a life that demonstrated that the overwhelming fact of injustice does not obviate or relieve in any way our responsibility to act against it. He showed that a person can simultaneously feel righteous anger about the world and radical optimism for it. We must affirm the creed to which he gave voice, that the work of creating the America we envision requires optimism and resolve.

“America never was America to me,” Hughes wrote in the penultimate stanza of his masterpiece. “And yet I swear this oath—America will be!”

For as much progress as we have made, America has yet to fully live up to its promise and founding aspiration to be a nation of liberty, dignity, and justice for all. Yet this noble vision remains as profound as ever.

At the Ford Foundation, our commitment to achieving this vision will not change. We resolve to continue fostering a fairer, more just America and world. We remain steadfast and unyielding in our support of the institutions and leaders fighting injustice and addressing inequality of every kind and category. And we are grateful for your leadership—and partnership—during the critical months and years ahead.

With appreciation and unbridled hope,

Darren