The Brazilian Amazon is a vast and imposing landscape, eight times the size of Texas—or some 560 million hectares. Home to roughly a third of terrestrial life forms, with 25 percent of our planet’s fresh water cycling through it, it’s an ecosystem that’s key to global carbon absorption and tempering climate change the world over. Indigenous peoples, quilombolas, rubber-tappers, coconut breakers, and other forest peoples who live in this region hold traditional knowledge that make them crucial stewards of its land, water, and forests.

The identities of these #GuardiansOfTheForest are deeply connected to the land, forests, and water, which they use in demonstrably sustainable ways. In the face of major threats from illegal loggers and miners, and pressure from huge governmental or private sector enterprises (like dams, farms, ranches, and highways), traditional communities continue to live in the forest without destroying or debilitating the ecosystem.

Some 160 million hectares of this region is officially recognized as community lands—designated indigenous peoples’ or quilombolas’ lands, extractives reserve, or sustainable use rural settlements. But more than 70 million hectares of public land has no official owners and remains under dispute. This means land tenure is extremely vulnerable, apt to be illegally poached or sold by the government to loggers, miners, and ranchers—who will shrink the forest, imperil its fragile ecosystems, and threaten the existence of the people who live there.

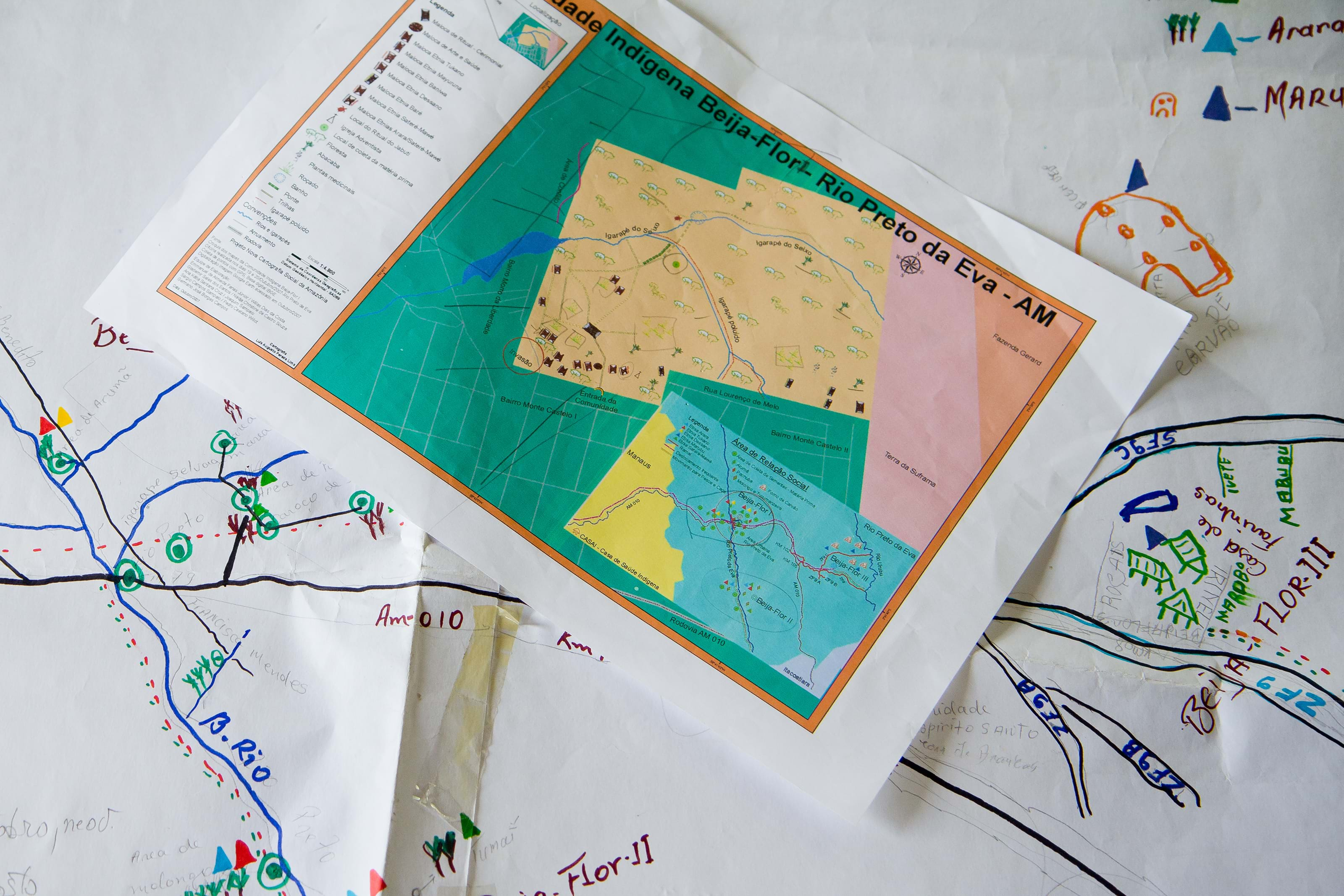

Because official maps often don’t plot their territories accurately, these communities have lacked the power and influence to control their own land and destiny. And they are often politically invisible, recognized simply as poor, and not as proud, knowledgeable indigenous, quilombolas, or rubber tapper communities. Thankfully, technology is starting to change this.

Built on the work of anthropologist Alfredo Wagner, the New Social Cartography Program of the Amazon (which is supported by the foundation) helps forest peoples throughout the region be recognized as groups with different identities, demands, and voices, and as people aware of their own cultural and development needs. The project works closely with communities to draw detailed maps they can send to local, state, and federal government in support of their territorial claims. Working with attorneys, geographers, anthropologists and others, forest communities learn how to use GPS and create data points on their maps that identify homes, plantations, bodies of water, and other sites of significance. Crucially, they determine what the maps highlight and signify, and the finished product represents a collaborative effort that is also wholly owned by the community. The initiative has plotted hundreds of communities onto maps in some of the most threated sub-regions of the Amazon. It has also inspired other mapping initiatives in Brazil and the Amazon region, as well as in East Africa and Mesoamerica.

Thanks largely to social cartography, earlier this year the quilombolas—descendants of slaves in Brazil who fled to the Amazon—were finally able to claim rights to more than 200,000 hectares of land. Their victory was hard-won, the result of a fight that lasted 15 years. In another victory for traditional peoples, in March Brazil’s Supreme Court dismissed a challenge from a political party that had attempted to overturn a 2003 ruling in support of the quilombolas’ rights. The court’s decision means that the quilombolas are now in charge of how their land is used, and also makes them eligible for an array of social programs (including subsidized housing) that they could not quality for without land titles.

There is a second, equally important way that technology is helping the Amazon’s guardians of the forest regain and maintain stewardship over their lands. The Geo-informed Agrarian Data System, a technology developed by the Federal University of the State of Pará (and supported by the Ford Foundation), maps and collects geo-information on public and private lands, which in turn helps verify land claims and assists in territorial disputes. With false or falsified land titles all too common in Brazil, this technology is helping to determine which are legitimate. Another technology, called Instrument, analyzes each case quickly and thoroughly, and sends information to those in the field who are adjudicating the turf wars that will determine the future not only of people who live in the Amazon, but people everywhere.

Technology has a promising role to play in the fight for local land rights all over the world. But mapping and other technologies do not and cannot operate alone: They need traditional knowledge, grounded in the land, to help realize their potential and truly help communities thrive.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.