kadir van lohuizen/NOOR

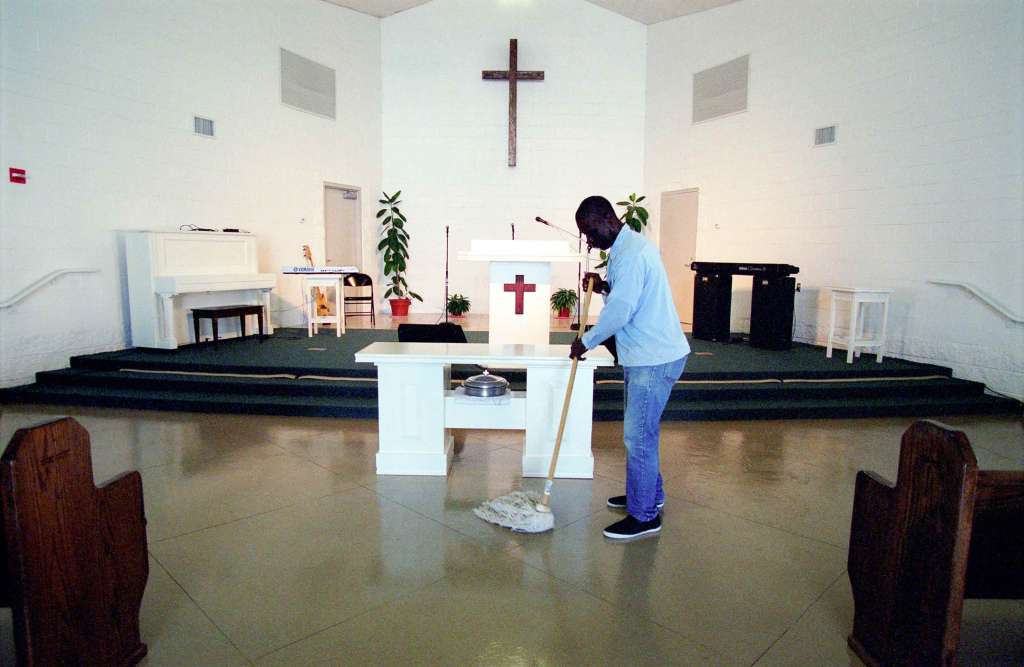

kadir van lohuizen/NOORDuring his travels around the globe, Pope Francis makes it a point to visit prisons. The people there are poor, powerless, and excluded—their dignity and humanity denied. To many free people, those behind bars are largely invisible. But through his visits to incarcerated men, women, and young people in correctional facilities across Italy, in Brazil and Bolivia, and now in the US, the pope invites us to see them.

This Sunday, Pope Francis will visit the Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility in Philadelphia, shining a light on America’s culture of mass incarceration. For beyond providing comfort and hope to incarcerated people, the pope speaks out against long prison sentences that ignore human potential and the capacity for redemption. A year ago, when addressing the delegates of the International Association of Penal Law, he cautioned against becoming enamored with incarceration:

A widespread conviction has taken root in recent decades that public punishment can resolve the most disparate social problems, as if completely different diseases could be treated with the same medicine … Scapegoats are not only sought to pay, with their freedom and with their life, for all social ills such as was typical in primitive societies, but over and beyond this, there is at times a tendency to deliberately fabricate enemies: stereotyped figures who represent all the characteristics that society perceives or interprets as threatening.

What must the pope think of America’s criminal justice system with its well-documented severity and racial disparities?

We have 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of its incarcerated population, with over two million people in prison and jail. Annually, we spend $80 billion to keep people behind bars, the vast majority are poor and more than 60 percent of people in prison are racial and ethnic minorities. The toll this takes on society goes far beyond the individual. Whole communities are starved of talent and opportunity to thrive, while government investments continue to focus on incarceration rather than education, health, and jobs. For the pope—whose concern with economic justice and opportunity reaches across social and class lines—our $80 billion investment must appear perversely counterproductive.

Of course Pope Francis is not alone in criticizing overreliance on incarceration, and its degradation of society. Two recent publications tease out its brutal economic toll on families—Ta-Nehisi Coates’s cover story for the Atlantic, and Who Pays: The True Cost of Incarceration on Families, by the Ella Baker Center, Forward Together, and Research Action Design. In “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” Coates demonstrates how the friends and families of people in the justice system bear extremely high financial, social, and psychological costs. Coates describes one set of parents who took out a second mortgage to pay for their son’s lawyers, and then a third as they incurred the “expense of having to make long drives to prisons that are commonly built in rural white regions, far from the incarcerated’s family … [and shoulder] the expense of phone calls, and of constantly restocking an inmate’s commissary.” In Who Pays, we learn that two-thirds of families had trouble meeting basic needs as a result of having a loved one in prison, and that over a third of the survey respondents went into debt to cover the cost of prison visits and phone calls with their incarcerated family member.

At the same time, corporations reap great profits from the system as it currently exists, with very little oversight. The Philadelphia prison hosting the pope this Sunday pays a private health care company to care for the people incarcerated there. According to In the Public Interest, that company, Corizon, makes over a billion dollars annually from government contracts in 27 states, despite huge concerns about the care they provide. In June, New York City ended its contract with Corizon after an investigation found mistakes by its employees had contributed to the deaths of at least two people at Rikers Island.

The pope’s visit reminds us that caging people en masse is more than a bad investment, it’s an immoral one. Earlier this week, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, a conservative who is working with progressives to end mass incarceration, said, “[a] cornerstone of the Catholic faith is that redemption is available to everyone, no matter what they have done. We are all sinners, and the ground is level at the foot of the Cross.”

America, too, can redeem itself for the sin of mass incarceration. Instead of investing in cells, our country must invest in what communities need to thrive—housing, health, education, and jobs. We can invest in alternatives to arrest, like the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion initiative that empowers police to direct people to community-based interventions instead of arresting them. We can repeal laws imposing lengthy and mandatory sentences, denying employment and voting rights to people with criminal records, and those leading to the incarceration of children. We can also provide real support to victims and survivors of crime, rather than promoting extreme sentences as their path to recovery and healing. The pope’s visit places a spotlight on the immorality of our justice system. Now it’s up to us to repent—and take immediate action to change our culture of mass incarceration.