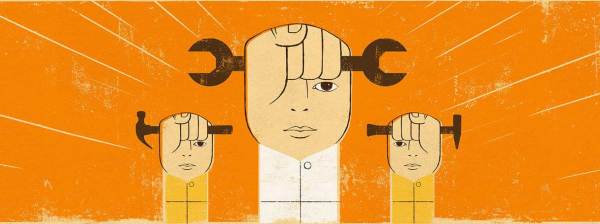

Resolving differences between corporations, governments and civil society organizations may be a matter of cultivating deeper human connections and broader thinking among their leaders. Otto Scharmer, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says companies and nonprofits must adopt a new mindset and pursue new forms of collaboration. Working across sectors will build relationships and trust, ultimately leading to systemic change, he says. But how do they navigate the gulf between them? Scharmer explains a four-step process designed to help leaders gain a new sense of perspective and tackle the challenges they face—together.

How do you bridge the divides between civil society, the private sector and government?

When you partner with business leaders or with leaders of civil society or government, each of them cannot address the key challenges that they face without the others and without partnering across sectors. That’s just part of the complex challenges that leaders face today. To address these challenges, we need to develop platforms of collaboration and innovation where we learn how to innovate at the scale of the whole—not only in small pockets but also at a systems level.

What we need is a mindset shift that moves from something that I call “ego-system awareness”—thinking only about your own community or your own institution—to “eco-system awareness,” that is, focusing on the well-being of all the stakeholders. As a leader, in order to be successful, you need to cultivate a set of relationships beyond the boundary of your own organization that crosses not only institutional boundaries but also sector boundaries.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

An equitable, sustainable supply chain

The Sustainable Food Lab is helping companies like Keurig Green Mountain address the needs of the small-holder farmers who grow their coffee—and understand that improving farmer livelihoods is good business.

You talk about a “tri-sector innovation” process. What is that and how does it work?

There are four key elements to making these complex stakeholder situations really work. The first is the power of intentions. You need to align people around a common intention. That already requires a lot of work, because in many dysfunctional systems today that common intention does not exist. You start by convening people who need one another in order to shift the system. You host multiple conversations around surfacing that common intention, which often means convening diverse people that usually would not talk to one another. Yes, from the left to the right, but it’s not just political; it’s really different cultures and worldviews that need to come together.

Number two: going on a sensing journey where they learn to see the problem through the eyes of the other stakeholders—where you give them methods and tools for listening to what they experience with an open mind and an open heart. It’s tools of deep listening and tools of empathy that make all the difference in their journey.

Number three: allowing the stakeholders to reflect and to connect with their deeper sources of knowing and self. In the end, there are two root questions of creativity: Who is my Self? And, what is my Work? “Self” with the capital S means “my highest future possibility.” “Work” with the capital W means “what is my real passion and purpose about?” It’s not like anyone has to come up with a specific answer, but it’s looking at your own life’s journey from a bigger perspective.

I remember at the end of one of these journeys of a tri-sector group, the country head of a global company said, “You know,” reflecting on his own journey, “I no longer work for my company. I work from my company.” What he meant is, “I still deliver value to my company, but these other dimensions of my work—the civic sector and the other stakeholders—they are equally important in my own decision-making.” I thought that was a nice way of framing it—from my company.

“What we need is a mindset shift that moves from “ego-system awareness”—thinking only about your own community or your own institution—to “eco-system awareness.”

Number four: rapid-cycle prototyping. How do you create trust and how do you create these new platforms of collaborating? By doing. And prototyping means doing something very quick, very small, very experimental and learning from the feedback you generate. We use that as the major tool in these multistakeholder processes, because it’s about accessing the intelligence of the head, heart and hand and learning from the stakeholder feedback that you generate by moving into action much faster and sooner.

Where has this strategy of cross-sector collaboration been successful?

One of the first examples of cross-sector collaboration between business and civil society is the Marine Stewardship Council. The Unilever managers saw lots of protesting going on in Germany over the Brent Spar oil facility in the North Sea. They saw this problem in another industry and thought, “Where is our own vulnerability?” They realized that in the food industry, with the overfishing that’s currently going on, if that continues without change, in maybe 15, 20 years, there’s no more business because all the fish stocks will be gone.

So from a self-interest perspective, which is the protection of the sustainability of their own business, they reached out to a credible NGO that would help them come up with a set of principles and practices that would make sustainable fishing practices mainstream. That’s why they created MSC—and that’s why it was not controlled by Unilever. Because if it’s controlled by one company, you cannot change the entire industry and what Unilever wanted was to change the industry. So they brought in other businesses. They brought in NGOs. They formed the Marine Stewardship Council and, while they didn’t solve the entire problem, institutionally they have been successful. It’s one of the first examples of this kind.

Other examples: With the MIT IDEAS programs in Indonesia and China, we have seen major successes with this approach to building tri-sector platforms for social and environmental innovation. Also, Unilever and Oxfam analyzed the entire value chain in Indonesia. And then Unilever and Oxfam also worked in Africa to promote sustainable sourcing practices at scale without destroying the smallholder structures.

Maybe the best example is the Sustainable Food Lab here in the United States and the Americas. The purpose is to make sustainable farming practices mainstream—it involves a number of major players in Europe and in North and Central America. It is making the entire supply chain more visible, more transparent and also more equitable, to some degree. It started with a process exactly around the key elements: a journey around sensing and connecting to your inner source of knowing and then prototyping. It doesn’t mean that all the problems are solved. But it is an example of how innovation can happen or begin to happen at the scale of the whole industry and not only in small pockets.

What do you mean by “new platforms” for collaboration and innovation?

I see social entrepreneurship as really having been one of the major forces of change around the world. But these initiatives almost never go to scale and they almost never change the system.

And what I see in big, old companies are younger leaders—the Millennials but also the people in their 40s—who are so under-inspired by the way companies and businesses are currently run and managed. And they would love to have more social impact. They would love to be part of a more inspiring narrative. In other words, there is a dormant potential of social entrepreneurship inside these big institutions that is not leveraged at all.

So when I say we need new structures and platforms for tri-sector collaboration, that’s what I have in mind. Why? Because these folks can’t connect to these other social entrepreneurs outside—they are boxed into these old structures.

There is a real hunger for thinking about economic evolution and economic innovation on a systems level, and current companies underdeliver on that. That’s why many people set up their own shop, create their own little venture or an alternative career path, or go to an NGO—because they offer a more attractive perspective.

OTTO SCHARMER

C. Otto Scharmer is a senior lecturer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management. He is founding chair of the Presencing Institute, a research community dedicated to social innovation. He works with representatives of business, government and civil society. With the German government and the Gross National Happiness Centre, a nongovernmental organization in Bhutan, he co-founded the Global Wellbeing and Gross National Happiness Lab, which brings together innovative thinkers from developing and industrialized countries to prototype new ways of measuring well-being and social progress. He has worked with governments in Africa, Asia and Europe and has led leadership and innovation programs at corporations such as Alibaba, Daimler, Eileen Fisher, Fujitsu, Google, Natura and PriceWaterhouse. He is the co-author, most recently, of “Leading from the Emerging Future: From Ego-system to Eco-system Economies.” He is a vice chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on New Leadership Models. He is currently building a U-Lab MOOC that will be launched via MITx on the edX online learning platform for social change makers around the world.

Personal website

The Presencing Institute

MIT faculty bio

Blog posts in The Huffington Post

Video of Scharmer lecture