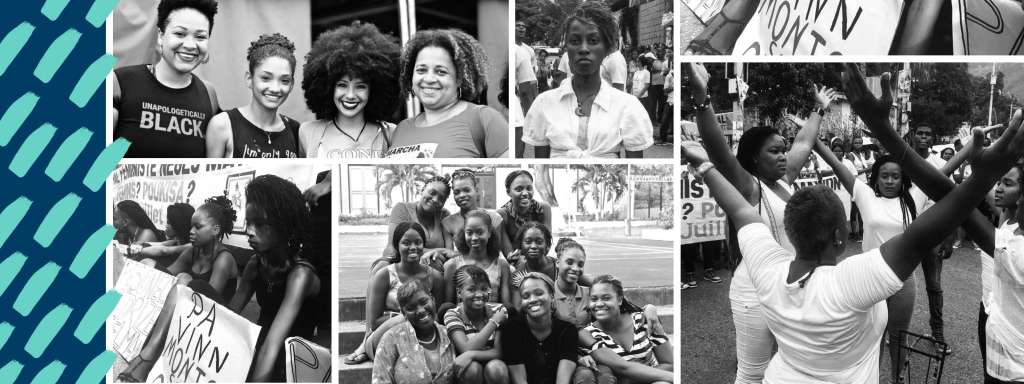

Courtesy of the Black Feminist Fund

Courtesy of the Black Feminist FundAround the world, intersectional movements for social justice are often being led by Black women from all backgrounds guided by feminist principles. From Sudan to Brazil, Black feminists are at the forefront addressing our most serious global issues today, from challenging authoritarian governments to fighting systemic racism and sexism, climate change and more. Even as Black feminists bear the brunt of these oppressive systems, they have proven effective in efforts to dismantle them—despite a major lack of resources.

In 2018, out of nearly $70 billion in foundation giving globally, less than half of one percent went to Black feminist social movements. Within more targeted human rights philanthropy, only five percent of funded organizations focused on issues affecting Black women, girls and trans and gender non-conforming people. And just one grant was given to support international Black feminist organizing.

This year, a new philanthropic organization, the Black Feminist Fund (BFF), was launched to tackle that problem. Created in partnership with women’s movements across the globe and led by three veterans of philanthropy and social justice—Hakima Abbas, Amina Doherty, and Tynesha McHarris—the fund is a first-of-its-kind vehicle focused explicitly on supporting Black feminist movements. With close to $30 million in seed investments from the Ford Foundation, Solidaire, Farbman Family Foundation, among others, BFF seeks to raise $100 million over the next two years to provide long-term, flexible support to Black feminist groups in Africa, the Americas and Europe. It will concentrate on groups working on issues such as violence prevention, resource rights around land, food and water, and cultivating the leadership of girls and young Black feminists.

Latanya Mapp Frett, CEO and president of the Global Fund for Women, which is providing infrastructure support to BFF as its fiscal sponsor, said the fund is long overdue. “The amount of philanthropic resources that go to women’s issues, period, is just embarrassing,” she said. “But when you start breaking that number down to women of color, then Black women, the numbers get more and more dismal. The necessity of BFF is to ensure we don’t go backwards, so we can work across the diaspora as Black feminist women, because we know that together we’re stronger.”

Courtesy of the Black Feminist Fund

Courtesy of the Black Feminist FundThe founders of the Black Feminist Fund Amina Doherty, Hakima Abbas and Tynesha McHarris. The first of its kind, the fund aims to end the chronic underfunding of Black feminists leading movements around the world.

“A lot of changes we see in my region come through work that is Black feminist-led, yet getting resources is hard and, when resources come, they’re very restricted,” said Mukami Marete, co-executive director of the East Africa Sexual Health and Rights Initiative and a BFF board member. “My dream is Black feminist movements being able to organize, knowing they’re supported in the long term. Because the problems aren’t going away any time soon.”

This past August, during Black Philanthropy Month, BFF’s founders spoke with Ford about their mission, the role of Black feminists in creating change, and their plans to shake up philanthropy.

How did the Black Feminist Fund get started?

Abbas: Being active in Black feminist social movements and philanthropy, we saw the barrier that a lack of funding poses. Yet despite this, Black feminist movements are creating radical change. We wanted to do our part in removing that barrier and felt it was time for a fund to significantly resource Black women, girls, and trans -led and -serving organizations, and that it should be a global endeavor, because whether in Africa, the Americas, or Europe, Black feminists and our movements are drastically underfunded.

What’s the importance of a fund specifically focused on Black feminist work?

McHarris: Oftentimes our movements aren’t seen because philanthropy creates silos, and Black feminists can’t silo themselves and say, “racial justice here,” “gender justice there.” We want to fund movements doing the most transformative, intersectional work but getting the least resources. We really want to support leaders and movements that acknowledge the fights around racism, sexism, xenophobia and imperialism are inseparable and interconnected. Winning one fight can’t come at the cost of compromising one battle with the other.

Doherty: And there’s a misperception in philanthropy that Black women are being resourced under the guise of mainstream development. This idea that, “Well, we’re funding education in Africa, therefore we’re funding Black women.” But that’s not the same as funding Black feminist movements with a mission to address the interconnected issues of sexism, racism, ableism, imperialism and xenophobia. Social change is being led by Black feminist movements in all the places we live, but change cannot happen if it isn’t resourced well and sustainably.

“The necessity of BFF is to ensure we don’t go backwards, so we can work across the diaspora as Black feminist women, because we know that together we’re stronger.”

What do we mean when we say that Black feminism works—that it is effective?

Abbas: We mean the imprint of Black feminists is everywhere in social movements. They are at the forefront of the fight in Brazil against what is essentially an authoritarian regime, not just by mobilizing in the streets against the genocide of Black people but also by taking political office, like Érica Malunguinho. In Sudan, Black women were very visibly at the forefront of upending Omar al-Bashir’s regime, while facing threats based on their genders and sexualities. We saw that also obviously with the Movement for Black Lives in the United States.

ASHRAF SHAZLY/AFP

ASHRAF SHAZLY/AFPAround the world, Black women are leading movements for justice. In Sudan, activist Zeineb Badreddine was one of the Black women at the forefront of the protest movement that ended autocrat Omar al-Bashir’s three-decade rule.

Doherty: Black feminists are also drawing connections between movements in ways that aren’t always visible. For example, the approach young Black feminists are taking to lead climate justice movements in the Caribbean is forcing governments to pay attention to various intersecting issues such as mental health, economic justice, access to land and food security. They’re saying, “The crises of our times have to be addressed by looking at what’s happening in the world around us and the connected nature of all of the issues we are trying to solve.”

What has the funding landscape traditionally looked like for Black feminists?

McHarris: Our hope is to boldly increase resources to Black feminist movements, providing flexible core support for up to five years and, eventually, up to eight years. We want to model for the philanthropic sector to fund Black feminists like you want them to win. That means you fund them for a long time because the struggle is long. You fund them at large levels; you don’t ask them to win freedom with $25,000.

Doherty: We have a dream of mobilizing $100 million over 10 years to go directly to movements. Part of our call is a callout—and a call-in—to philanthropy to put their money where their mouths are. In the current landscape, folks talk about how important social justice is or funding Black women is, but the resources to accompany that work is nowhere near enough.

Abbas: We also want Black feminist movements’ experience with funding to be different, so they can share their ideas and wealth in ways that feel authentic and not have to do acrobatics to fit whatever guidelines traditional philanthropy imposes. As Black women, we’re always confronted with a society that responds to us with a “no.” With BFF, we want to start with a “yes.” What we’ve found so far, in every conversation we’ve had with Black women in all their diversity, is that within a few minutes they’re using the language of “we” and “our” to talk about BFF, because it’s an institution they feel ownership of. They are the vision and they are part of it too.

Tell us about your goal to build a global network of Black donors.

McHarris: This October, we’re organizing a convening to engage Black women across philanthropy to dream and strategize together. We know that our base exists already and we just want to bring folks together, especially on a global level. We’re excited about engaging Black philanthropists who can donate to BFF boldly, because that’s going to be an important message to philanthropy: to acknowledge the power of Black feminist dollars.

When we think about Black feminists who can fund, it’s all of us. Some of us are giving our dollars, and a lot of us are giving in other ways—with our leadership, our labor, and our expertise.

Doherty: In our first few months alone, we galvanized close to $10,000 from individual donors giving at any level they could. In many parts of Africa and the Caribbean, we have what we call the “throwing box” or “sou-sou”: small ways for a community to support one another. This is an example of a global community that, even in a pandemic, put its resources behind this dream of a Black Feminist Fund. Our goal is to get to that $100-million mark as quickly as possible, so that we are able to make those long-term commitments.

Abbas: There’s a narrative in philanthropy of Black women being passive recipients of aid, particularly in the Global South. We intend to turn that on its head and show how Black feminists are giving—and always have—and that funding can flow from the Global South to the Global North.

Cris Faga/NurPhoto

Cris Faga/NurPhotoIn Brazil, Black women have been leading the fight against the racism and sexism in the country—from protesting in the streets to running for political office.

Which sorts of projects are you looking to support?

McHarris: There are so many movements we’re excited by. When we think about resource rights and ecological justice, we want to support Black feminist movements that acknowledge the leadership, power and genius coming from folks on the ground right now. When we think about safety and peace, there are models across the world of Black women creating support systems to respond to gender-based and state-sanctioned violence. When we speak about young people, there are Black girls who are leading work right now all over the world.

Doherty: I’m excited about the opportunity for connection across language, continents, and all the places we live. A big part of what we want to resource is the opportunity to link movements, so we can share knowledge, writing and lessons. These things get swept under the rug, but I think relationship-building forms the heart of our movement and will help us succeed.

How does BFF fit into the longer history of Black philanthropy and giving?

McHarris: History has shown us that Black women are the most philanthropic, but those stories aren’t being told. It might not have been a fund before, but a grandmother taking care of folks on her block. We consider ourselves part of that long legacy of giving. At the same time, this is the first global fund resourcing and connecting Black feminists to each other and to Black women donors and their allies in institutional philanthropy. Our hope is that, generations from now, BFF is part of the story that changed the landscape, resourcing Black feminists so boldly that we’re not in the same conversation about lack of resources anymore.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.