Nomonde Nkosi stood before the door of her small, cement-block home, gesturing toward a plume of black smoke rising in the distance. “The air is smoky,” she said, “and when they blast, I can feel it from where I am. The house shakes.” Nkosi’s province of Mpumalunga accounts for 83% of South Africa’s coal production, with 12 mining companies and numerous coal-fired power plants, one of them approaching 100 years old. We South Africans instinctively associate the region with chemical-laden air, so much so that visitors invariably complain of scratchy throats and soot-dusted skin. Meanwhile, communities in Mpumalanga lack even the most basic necessities, with electricity so expensive few can afford it, and local streams that run brown thanks to contamination from the mines.

These days, though, Nkosi, a committed community activist, entertains a wary hope that a brighter future might lie ahead. Like the rest of the world, South Africa is looking to transition from a fossil-fueled economy to one that’s driven by clean, renewable forms of energy. We know it won’t be easy: My country is home to no fewer than 90 mines, and we rely on coal for 87% of our electricity. (Even that doesn’t cut it. Poor management and corruption at Eskom, the state-run power company, have left us dealing with power cuts for the last several years. Those of us on the grid often have to go without electricity for up to six hours a day.)

But two years ago, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, established a landmark Climate Commission, and he ratcheted up our obligations under the Paris Climate Agreement. Last November, at the COP26 gathering in Glasgow, the government struck a deal with the United States, Britain, France, Germany, and the European Union. Known as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), the agreement—which Foreign Policy called “the most impressive thing to come out of the summit”—is designed to provide $8.5 billion in grants and affordable loans over the next five years. All in an effort to enable South Africa to retire its aging coal plants, construct cleaner energy sources, and support the millions of people living in coal-dependent regions who will need to quickly reimagine their lives.

The question is how we pull off the “just” part of the transition for folks like Nomonde Nkosi, who’ve been left behind for so long. How will we cushion the blow of deindustrialization in a nation that, despite its vast natural treasures, still lags behind in development and traps millions of citizens in poverty? South Africa’s unemployment rate already ranks among the highest in the world, and the Just Energy Transition threatens some 120,000 jobs, most of them among heavily unionized mine and power-plant workers.

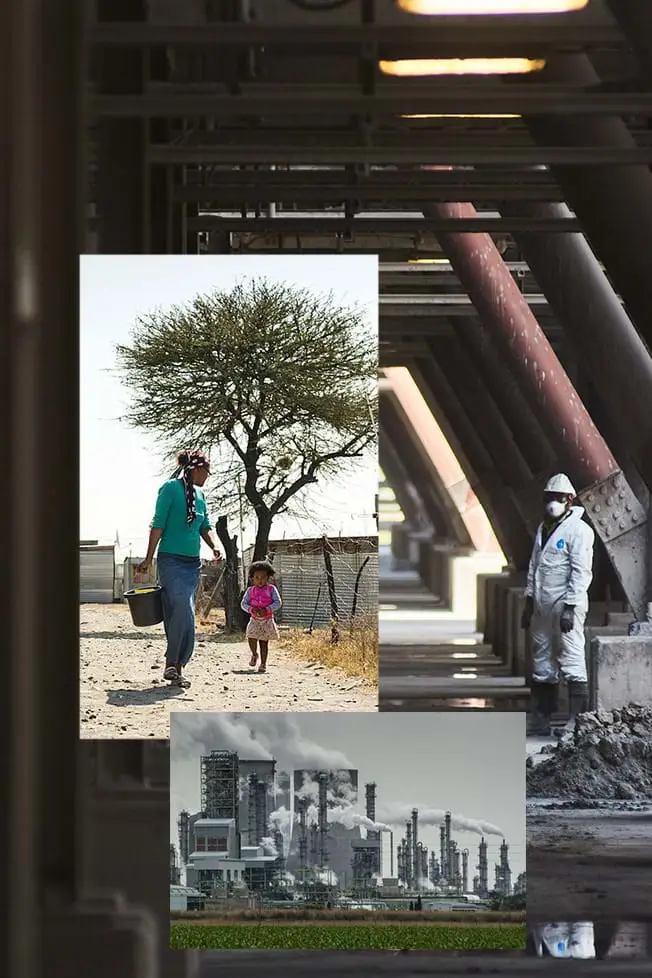

Getty / Bloomberg

Getty / BloombergSouth Africa relies on coal for 87% of its electricity, but residents across the country, from informal settlements to rural communities, live without reliable power. Eskom, the state-run power company, has struggled to supply adequate access.

Many of the specifics around the loan arrangements remain murky. While the commission has conducted community stakeholder engagements in various parts of the country, these communities, which our grantees work with, express a concern about what’s actually being done to roll out the transition. “Our government talks very passionately about climate change and resource governance,” said Claude Kabemba, who directs the Johannesburg-based Southern Africa Resource Watch (SARW). “But there aren’t very progressive policies in place, and there’s always a gap between policy and implementation. Even where you find great policies, the implementation is not always there. Or if it’s there, it’s haphazardly done.”

In places like Mpumalanga, life has revolved around coal for as long as anyone can remember. Most people work at the mines and those who don’t labor for company-supported schools, transit operations, or shops that service the mines and their workers. And the fallout from the industry literally flavors—or rather taints—the air they breathe and the water they drink. But as Eskom looks to decommission its plants there, the community will need to change everything about the way it functions.

The few government consultations that have taken place, Kabemba says, have come without advance notice, giving communities no time to gather their thoughts around the transition they’d like to see. It’s a shame, he adds, because the Mpumalanga residents, who have spent decades advocating for themselves in the face of the fossil-fuel industry and developed a strong activist voice, should be an important ally in realizing this transition. It’s for this reason that Kabemba and his team at the Ford-funded SARW have tapped the community, and, in particular, a group called WOMANDLA, founded by Nkosi and other local women, as key partners in ensuring that the government fulfills its promise to implement a just transition.

Getty / J. Countess / Gallo images

Getty / J. Countess / Gallo images Getty / Bloomberg / Foto 24 Gallo images

Getty / Bloomberg / Foto 24 Gallo imagesSouth Africa’s Climate Commission holds incredible promise not just for the country, but the continent—and the world. With an $8.5 billion commitment, it has the potential to transition the country from coal to clean forms of energy and show other resource-reliant nations a sustainable way forward.

Women, as local activist Pinky Langa points out, are most familiar with the life of the community, and understand its collective hopes and fears. “Women are the first to take on additional work when the mining companies come. When the companies are blasting, it’s the women who must continuously wash the curtains and the linens in the house. They’re the ones who take care of the kids who’ve gone to the stream and drunk contaminated water, or who now have chest problems because of all the dust.”

A Ford Global Fellow, Langa grew up in Mpumalanga, not far from Nkosi, and she harbored dreams of following her uncles into the mining business—until she learned that the ubiquitous flames, smoke, and sinkholes that marred her childhood were the ugly aftermath of decommissioned mines. While mining executives living in company housing enjoy electricity and clean water, those in the adjacent settlements are left to rely on the local government. Often a week will go by before anyone fills the public water tanks, forcing residents to resort to the dirty streams. The companies arrive with promises of jobs, schools, roads, and clinics, Langa said, “but at the end of the day, we’re left with the liability. When they come, we still have our trees, our biodiversity, but when they leave, there is nothing.”

“This transition is not just about energy, it’s about a new economy that needs to be put in place, one that must bring along those who’ve been forgotten in the current economy.”

As a part of her advocacy work in the coal communities, Langa helps women pursue economic opportunities unrelated to the ubiquitous industry. She’s watched several go on to establish their own businesses, from hair salons and vegetable stands to tailoring shops and cosmetics boutiques. One currently serves as ward councilor, representing her constituents at the municipal level. It’s these strong women that SARW supports, helping them to hone and amplify their messages, so they then can train a wider network that will find a voice in policy conversations at the national, regional, and, ultimately, the global level. To realize a just transition, Kabemba said, “Whatever comes from the communities must be as important as what comes from the government, from civil society, from the private sector. That voice must be present in the conversation.”

While the communities have expressed a clear desire to divest from coal, their motivation derives less from the threat of climate change and more from the tarnished legacy left by the extractives industry. “Mining has put them in a worse situation, where their water is polluted, their air is polluted, their houses are cracked,” said Mashudu Masutha, a senior program officer with SARW. They don’t want to merely get rid of coal, they want a better life. They want jobs and economic mobility. The mining companies have been in Mpumalanga for decades, but, she says, you’d be hard-pressed to find a miner who’s moved beyond a hand-to-mouth, paycheck-to-paycheck existence.

Getty / Bloomberg

Getty / BloombergWhat will a “Just Energy Transition” look like—and how to pull it off—is still very much in question. When life has revolved around coal for as long as it has in South Africa, a shift to more renewable types of energy like solar requires ensuring the most at-risk communities understand the impact of their choices and can fully participate in designing and implementing plans.

But what will life after coal look like? What becomes of South Africa’s economy? “There’s just not enough information,” Masutha said. “When we talk about the Just Transition in my language [Setswana], there’s no word for it. You have to try to explain it in practical terms, but it’s difficult to do it in a way that doesn’t cause anxiety and fear.”

While some argue for phasing down coal operations rather than an immediate phase-out, for instance, others believe coal mining and energy production can continue under a greener guise, thereby preserving jobs. Both the government and the industry talk about “re-skilling” laborers for the new economy, but nobody’s sure what that looks like. Masutha recalls a slick presentation from one of the multinational mining companies on how it intended to shift to a sophisticated, green form of extraction. Its solution? To become fully automated, thereby forgoing the need for human labor.

When it comes to how South Africa should define “just,” the community remains divided. While miners are afraid of losing their jobs, it’s not only them who stand to lose. Teachers, cleaners, shopkeepers—anyone whose livelihood depends on the mines and the economies they engender—will need to reimagine their future. These communities are not always in agreement; each has their own needs and definitions of “just.” To ensure the transition works for all, it will require transparency and access to information so communities have a complete understanding of the impact of their choices and can fully participate in designing and implementing plans. It will also require a delicate political dance at every level of society.

“This transition is not just about energy,” said Kabemba, “it’s about a new economy that needs to be put in place, one that must bring along those who’ve been forgotten in the current economy.”

Discussions among policymakers about future scenarios tend to revolve around agriculture and tourism. Mpumalanga isn’t far from many of the country’s storied game lodges and private hunting facilities, so the province could conceivably expand in that direction, but it would require eliminating the foul smell that tourists inevitably remark upon en route to greener pastures. As for agriculture, chances are slim it’ll take root in a place where the soil, water, and air remain polluted. Especially when its success hinges on a generation that has come of age in the Coal Belt and never learned a thing about farming.

Langa and SARW host workshops to educate communities about how they might benefit in the new economy. For instance, they encourage learning to manufacture and install solar panels, generating electricity and selling the surplus back to the municipality. But aside from a very few examples—one of the country’s oldest mines has been transformed into a shiny museum and waterpark—few projects exist to illustrate what might be possible.

“People are anxious and fearful,” said Melissa Fourie, executive director of the Ford-funded Centre for Environmental Rights and a sitting member of the President’s Climate Commission. Like Kabemba, she believes “just” is something much bigger than alternative energy, and has been pushing to ensure that civil society has a say throughout the process. “It’s a much deeper discussion than simply, ‘Oh, we’ll do agriculture. We’ll bring tourists.’ How do you prepare the community for that new normal? What are the measures, step-by-step, that must be taken, and where are the funds to support them?”

Fourie, like many, believes that the plan should incorporate reparations to address the health impacts of mining and coal-based energy production. A recent report found that more than 5,000 South Africans die annually from the effects of pollution in its Coal Belt. “In Mpumalanga,” she said, “where the water’s been polluted and the soil’s been destroyed by coal mining, how do we compensate for the health outcomes they have sacrificed for themselves and their families? How do we get women to start benefiting in the green economy we’re building? How do we deal with issues of safety for women? How do we ensure things like solar lighting and electric bus fleets for future generations?”

Getty / Gallo Images

Getty / Gallo ImagesTransitioning to clean energy threatens 120,00 jobs in South Africa’s coal mines—and that doesn’t include those livelihoods affected by the industry . The government is exploring agriculture as a way to power a post-coal economy, but it seems unlikely to take root in a place where the soil, water and air remain polluted.

Saliem Fakir, who directs the African Climate Foundation, another grantee, takes an even bigger-picture view. “South Africa needs a structural change in its dependency on coal,” he said. “And the way to make that happen is to shift the mindset of the state.”

Fakir played a key role in securing the arrangement in Glasgow, and he does most of his work at the national level, striving to convince governments to imagine a different sort of future. “It’s about awakening people to a changing technological world, a changing global economy and geopolitical scene,” he said. “How do we enable decision-makers to invest and plan in a way that brings them closer to the new world, and adapt to the challenges that remaining in the old one will create?” If South Africa doesn’t begin preparing for those changes, it will get left behind.

Fakir also works with policymakers on developing reforms that will help open the space for alternatives and finding ways to invest in those alternatives in the context of a country’s economy—all while ensuring that those most affected are brought into the conversation. Beyond South Africa, he’s been partnering with local authorities in mid-size cities across the continent to figure out how to find and implement cheap electrification solutions. How should states allocate resources to finance such investments, and how can the taxation of renewable energy best benefit these new economies?

“We have to not make assumptions that just because we are providing a cure for one parameter of the problem, which is carbon emissions,” he said, “that we don’t unsettle a whole social and socio-economic infrastructure that’s been built on something that was there before, and that we can replace with something better.”

All this will require countries to rethink their investments in health, education, and safety nets for the unemployed, including the possible provision of a basic income grant. It’s a notion that, in the wake of the successful relief package South Africa’s government rolled out here during COVID, no longer seems as far-fetched as it once did.

At the same time, Fakir acknowledges the grassroots engagement upon which everything else relies. “Activism is crucial to building local networks,” he said, “because ultimately this is about political and economic reform.” He believes that a broader base is necessary to transform both the conception of climate and its location within the political economy. That means improving the relationships between government, big energy, social-justice movements, and vulnerable communities, so together they can make sure the government, long cozy with the fossil-fuel industry, isn’t simply paying lip service to the concept of a Just Transition. (It’s been a decade since 34 protesting miners were gunned down by the police outside a platinum mine in the town of Marikana, for example, and we are still waiting for those responsible to be held accountable.)

Getty / Bloomberg

Getty / Bloomberg Getty / Alistair Routledge / Xinhua News Agency / John Lamb the image Bank / Foto 24 Gallo images

Getty / Alistair Routledge / Xinhua News Agency / John Lamb the image Bank / Foto 24 Gallo imagesWhile much hangs in the balance, communities and the organizations that serve them are keeping a sharp eye on every move of this transition and ensuring the voice of the people are part of the conversation. Communities are invested and believe a change is long overdue. As Mashudu Masutha, a senior program officer with SARW, said: “They don’t want to merely get rid of coal, they want a better life.”

Amid it all, concerns remain about how, exactly, the financing will work, whether the loans will actually materialize, and how, in dispersing them, the government can avoid the corruption for which the extractives sector has long been notorious. The agreements entail loans of different sorts, and some worry that the country won’t be able to repay them, particularly if we are slamming the brakes on some of our most lucrative industries. “Part of our role is oversight,” said Fourie, who is among those arguing for an increase in domestic funding to complement the investments from outside the country. “We can’t do that without proper transparency about where this money is coming from.”

“Who’s going to control the money?” asks Kabemba. “The same group of entrenched elites?” It isn’t just the government, but multinational and local corporations, that stand to benefit from a preservation of the status quo. “Our challenge now is how to shift the power in favor of communities.”

In November, representatives from around the world will gather in Egypt for COP27, the first time the global conference will have been held on the continent. Kabemba hopes that as people recognize the critical role that Africa plays in driving a climate-controlled future—not just in supplying the minerals required for securing green energy, but in preserving the vast rainforests and peatlands of its Congo Basin—the global community will recognize its value and support its efforts. Though Africa contributes but a fraction of global emissions and still lags far behind where development is concerned, Kabemba said, “We have committed to address the issue with the same vigor as those who’ve polluted.”

“You go to these community meetings and people are angry, they are furious with the way the government has let them down,” Fourie said. “But they’re still hopeful, and they’re still demanding, and they’re ready to offer their own services to fix things. If they could see the wind farms going up, the solar panels being installed in townships—and people actually having electricity, as opposed to sitting in the dark—that would be huge.”

There is no question that our country has the resources and the infrastructure to get this job done right. Our government must be meticulous both about implementing sound policy and maintaining absolute transparency as it carries out these fundamental reforms. Any missteps could provide fodder for other world leaders looking to drag their feet and provide excuses as to why business should carry on as usual. With war raging on in Ukraine and European countries beginning to sacrifice their ancient forests for heat, the issue of climate is increasingly taking a backseat, with billions in financial commitments hanging in the balance.

If, on the other hand, South Africa succeeds, we will stand as a role model for the world. We have already begun to see other countries in the Global South drawing up blueprints for Just Transitions modeled on our own. Given the backing we’ll require from the global community and the philanthropic sector, South Africans could find ourselves, within a decade, producing and exporting batteries and electric vehicles while at the same time enjoying cleaner air and water, better health outcomes, and a far more equitable distribution of wealth. If a Just Transition can help South Africa reimagine a new economy and evolve into a more just society, imagine the possibilities for the rest of the world.