Twenty years ago, just a 20-minute taxi ride from the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice, the Twin Towers crumbled. It’s hard not to think of where we were, or how it affected our lives.

For one of us (Maria), September 11, 2001 came just days after moving to New York City, with the destruction and devastation sending waves of chaos and grief through the streets of my new home. Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away in Michigan, I (Noorain) was just a teenager. At the time, I wore a hijab—and I immediately began to experience the verbal attacks and threatening atmosphere that so many of us encountered for two decades. I was terrified—not just for myself and my family—but for entire communities of Muslims, Arabs, immigrants and others in the United States.

Although our experiences are unique to each of us, our memories of that day have lasted decades—and they continue to inform our work here at the Ford Foundation.

Today, the events of September 11 and the racism and xenophobia that followed still shape the lived experiences of millions—including us. Over the past two decades, Ford has partnered with groups in New York and across the US to rebuild a more just city, country, and world.

Immediate Impact—and Philanthropy’s Response

For countless New Yorkers, uncertainty pervaded the weeks after the attacks. Many critical services had been disrupted and, as first responders worked around the clock to clear debris, communities and nonprofits needed support to survive, sustain, and continue their critical work.

For example, the Coalition for Hispanic Family Services, which administered a foster care program for over 200 children in New York, was one of many nonprofits whose operations or finances were disrupted by the attack. The Coalition depended on funding from the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), but the ACS offices, just blocks from Ground Zero, were closed for weeks following September 11, delaying payments to the Coalition and the foster families they supported. So the grantmaking community immediately stepped in—led by the Fund for the City of New York, among others.

We were proud to contribute $1 million to the fund’s efforts, which provided immediate cash-flow loans to nonprofits whose work had come to a halt, including the Coalition for Hispanic Family Services. Payments to foster families resumed, preventing one catastrophe from compounding another.

Ford also contributed $5 million to the September 11th Fund, founded on the day of the tragedy and chaired by our former president Franklin Thomas, to support victims, their families and others affected by the 9/11 attacks. As Joshua Gotbaum, the fund’s executive director, remembers, Ford’s primary focus was to resource and stabilize “nonprofit institutions—those institutions that are essential to the fabric of the community.”

The Rise of Racism—and Movements for Justice

While philanthropic, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations filled gaps, for many communities across the United States, the terror continued.

Just four days after September 11, Balbir Singh Sodhi, a Sikh American, was planting a garden outside his convenience store in Mesa, Arizona when he was killed by a man who profiled him as Muslim. Sodhi’s murder was the first post-9/11 hate crime, and sadly far from the only incidence of bigoted violence. In 2001, Black/African, Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim, and South Asian (BAMEMSA) communities endured 17 times more hate crimes than in 2000. Acts of violence continue to this day.

Don Bartletti/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Don Bartletti/Los Angeles Times via Getty ImagesIn Arizona, the BAMEMSA community created a memorial in honor of Balbir Singh Sodhi outside the convenience store he ran in Mesa.

These attacks continuously add to this national tragedy. In fact, Sodhi’s name sits alongside other victims on Arizona’s official 9/11 memorial.

These casualties themselves are part of a much larger unjust system that targets millions based on their race, ethnicity, and religion. Capitalizing on latent xenophobia and white supremacy, post-9/11 policies stirred a frenzy of fear fixated on Black and brown people. From the Patriot Act passed the month after the towers fell to the Muslim ban upheld in 2018 by the United States Supreme Court, BAMEMSA communities have been surveilled, monitored, exploited, scapegoated and dehumanized for decades.

And yet, rather than submit to these injustices or back down in the face of discrimination, BAMEMSA communities experienced a mass political awakening, constructing an innovative, coordinated, and fearless movement to challenge inequality at every turn. And we saw just how essential nonprofits are to a society so torn.

That movement built a civil rights infrastructure to disrupt systematic profiling and persecution. For instance, Muslim Advocates, a nonprofit founded in the wake of the Patriot Act, provides legal representation for Muslim Americans targeted by discriminatory post-9/11 policies and practices, including over-policing, surveillance of houses of worship, and the Muslim ban. The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding has been a key source of relevant, rigorous, solution-seeking research on issues affecting BAMEMSA communities. This foundation of facts has been critical to move the public, policymakers and media towards a more equitable definition of inclusion.

These groups and others have inspired a wellspring of innovation in philanthropy, such as pooling resources through collaborative funds like the RISE Together Fund and Pillars Fund. Interwoven, agile new institutions like these make up the connective tissue of the BAMEMSA movement.

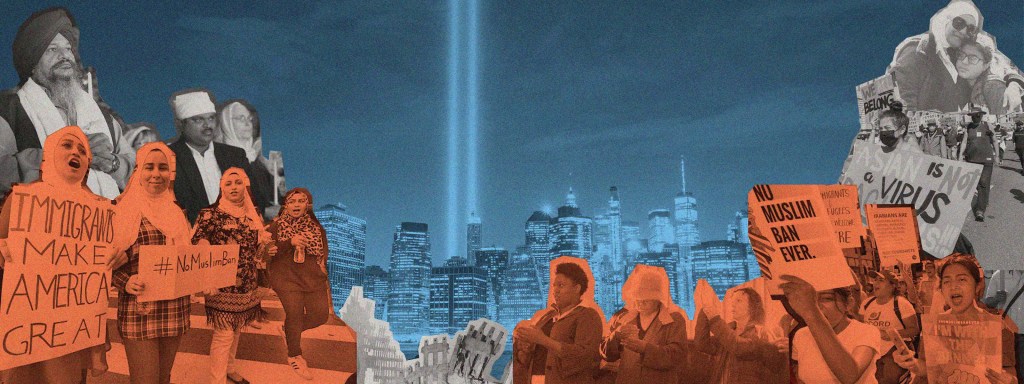

Ronen Tivony/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Ronen Tivony/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesIn 2017, President Trump rolled out a travel ban, restricting travel from Muslim-majority countries, sparking protests across the US at airports and in city centers.

BAMEMSA activists leveraged the power and promise of these pooled funds to engage in widespread solidarity and coalition-building. From litigation and community-led tracking of hate violence, to mobilization efforts like the #NoMuslimBanEver campaign, grantees such as the Asian Law Caucus, South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT), the Center for Constitutional Rights, Brennan Center for Justice and so many others have spent the last two decades building a more just nation at every level, together.

In addition to civil rights, they’ve taken on the prejudice that pervades post-9/11 American culture. Take, for example, Pillars Fund, USC’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, and its Ford-supported project, Missing & Maligned, launched in June, which exposes the erasure and demeaning portrayals of Muslim characters in film. With support from prominent creatives like Riz Ahmed, this initiative spotlights one of 9/11’s most insidious legacies—the toxic narratives that distort the perception and self-perception of BAMEMSA individuals—and provides concrete recommendations for the film industry to support Muslim stories and storytellers.

Missing & Maligned, a project funded by Ford, exposes the erasure and demeaning portrayals of Muslim in film and proposes solutions to improve representation across the film industry.

Most importantly, this movement fights for not just the Muslim community of today, but for the Muslim community of tomorrow, including all the young leaders across the BAMEMSA community who comprise it. Initiatives like SAALT’s Young Leaders Institute and Deeply Rooted Emerging Leaders fellowship among others have given space for young people to build leadership skills, connect with activists and mentors, and explore social change strategies around issues that affect their communities. These rising leaders give us hope for a world free of the bigotry that has marked the past two decades.

Facing New Crises, 20 Years Later

Twenty years on, BAMEMSA communities continue to advance justice amidst another crisis: COVID-19.

As with 9/11, the pandemic has provoked racism and xenophobia, this time against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. Hate crimes targeting AAPI individuals have skyrocketed since 2020. During a pandemic that has disproportionately harmed immigrants and people of color, these same communities have faced increased fear, hate, and violence.

Ray Chavez/MediaNews Group/The Mercury News via Getty Images

Ray Chavez/MediaNews Group/The Mercury News via Getty ImagesSince the start of COVID-19, the AAPI community has experienced a surge in hate crimes, calling to mind the racism and xenophobia directed at BAMEMSA communities after 9/11.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Mario Tama/Getty ImagesTo respond to this moment, we are funding efforts to support the AAPI community and reshape public understanding of what it means to be an American.

Fortunately, the philanthropic community knows more about responding to the unimaginable today than we did 20 years ago.

Similar to the weeks after 9/11, we recognized the existential threat facing many nonprofits amidst this unexpected catastrophe. In response, we issued a first-of-its-kind social bond to unlock a billion dollars in additional funding when our grantees and the communities they serve needed it most.

And to address the wave of hate crimes against the AAPI community, we’ve sought to challenge racism and xenophobia at both individual and institutional levels. As part of The Asian American Foundation’s Giving Pledge, we committed $150 million over the next five years to promote racial justice, civic engagement, and arts and culture in AAPI communities. We also supported its “See Us Unite” campaign, which increases awareness of anti-AAPI bigotry and works to reshape public understanding of what it means to be an American.

These efforts stand on the shoulders of the BAMEMSA movement and many others.

Philanthropy’s work is only beginning

Two decades of BAMEMSA ingenuity and imagination have built a robust infrastructure in the fight for justice. However, given the mounting attempts to demonize those communities, we must reinforce this infrastructure to fuel generations of lasting change. That’s why we proudly join the RISE Together Fund and allies in calling on funders to invest meaningfully in this movement.

Along the way, we must stop and reflect, as we have today, and learn from our setbacks and shared progress. The unrelenting courage, vision, and leadership of BAMEMSA communities shows us what building a more perfect union takes—and how, in the rubble of the current moment, we can rebuild together, united in our commitment to justice and one another.