Illustration by Sonia Pulido

Illustration by Sonia PulidoIn the late fall of 1863, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to a small town in Pennsylvania, the site of the American Civil War’s bloodiest battle. On that sunny, November day—the war still raging—Lincoln addressed the ages. The republic, he said, was engaged in a great battle, testing whether democracy can long endure.

Nearly 157 years on, we, too, are engaged in a test of whether democratic values and institutions can endure. And the test is happening everywhere, all at once.

It’s become commonplace to note that America faces a pandemic of pandemics: Fear and fire and fury that betray corruption and climate catastrophe and callous indifference to 400 years of a racialized caste system; a lethal virus and subsequent economic fallout that lay bare the profoundly unequal ways in which we survive or succumb—in which we live and die. Already, America has lost as many people to the coronavirus during the last eight months as during the two-plus years of battle leading up to that decisive conflict in Gettysburg.

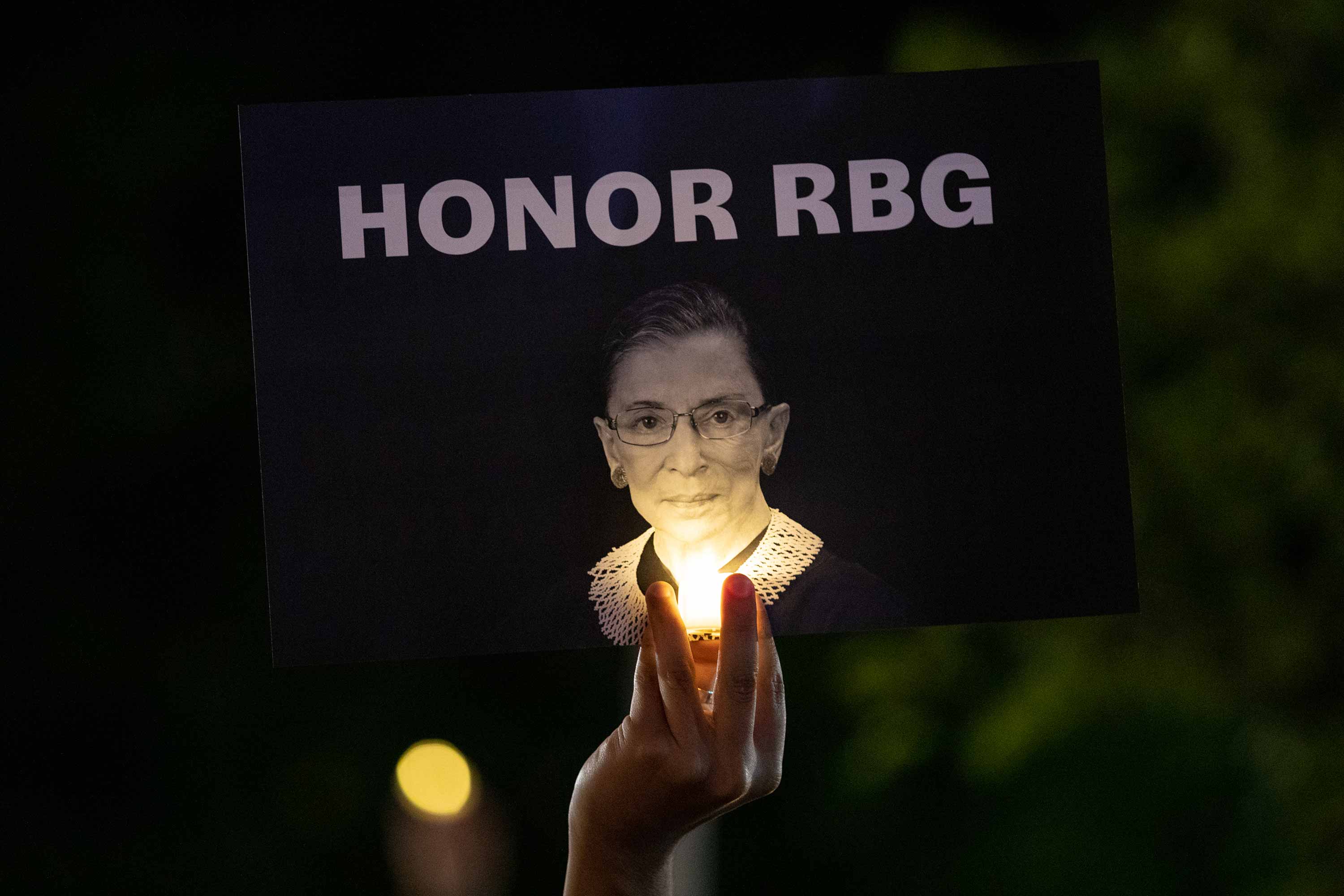

In this context—in any context—the passing of icons Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Congressman John Lewis felt like heavy blows. And, in addition to the lives we mourn, we grieve countless other losses: Visits with family or meals with friends. A first day of school. Plans cancelled, and dreams deferred. Birthdays, graduations, and holidays—all those rites of passage, stolen. Lost forever, a precious moment to sit with a loved one in their final days, or a memorial service to say goodbye.

In these cases, some of us might say, “thank goodness for technology”—for the video calls and internet service that keep us connected. But I grieve for those children without tablets and laptops and high-speed connections at home, in urban communities and rural ones alike. Shame on us for asking students—some 12 million kids across the United States—to click into classrooms from the parking lots of fast-food restaurants.

This is hardly the only way inequality has announced itself, or amplified our anguish. The statistics and stories abound.

A couple of weeks ago, clicking through the channels late at night, I landed on C-SPAN’s Washington Journal. The producers had opened the phone lines and invited Americans to share how the pandemic had affected them. Some people had lost their jobs, but not received the unemployment checks promised to them. Others were staring down an eviction or a foreclosure. Thea, from South Carolina, openly wept as she described her situation—her desperation and anxiety about merely caring for herself.

As she spoke, I found myself weeping with her. Her story was a gut punch—a visceral reminder of how much people are hurting.

Our converging crises—these unceasing traumas—continue to exact a physical and mental toll from each of us. The road here has been exhausting; the road forward seems daunting, especially when it feels we are careening out of control or teetering on the edge of a cliff.

This is a season of suffering—in the United States and around the world. The sum of all this suffering, of all this mourning, of all this daily grief, can be a crushing burden to carry, especially when it feels as though we must carry it on our own. We’re all grappling with our own version of what Michelle Obama rightly called “some form of low-grade depression.”

And as we bear all of these trials, there is another test—a test akin to the one Lincoln described—that will determine whether and how democracy can long endure: A test of moral leadership.

A test of moral leadership

We know what effective leadership looks like. When faced with any crisis, with any kind of uncertainty or upheaval, we instinctively look to our leaders—to the people we respect and admire, who call on us to be and do better. As children, it starts with the parents, teachers, and coaches, and other adults in our lives. As students, we pore over those profiles in courage: the stories of statespeople who attended to our ancestors through adversity. At work, we look to the executives in charge or generals in command. We look to authority figures in their various disciplines—the doctor at the hospital, the principal of the school—to exercise their expertise; to organize and orchestrate; to challenge, encourage, or inspire. To tell the truth.

We should expect no less of our elected officials and the institutions they steward, especially times of local, national, and global crisis. At minimum, we expect some basic level of competence and compassion.

We also know what the downfall of leadership looks like. We have seen the perils associated with immoral leadership. We’ve seen firsthand how quickly democracies can decay into autocracies—whether in Europe, Africa or Asia, the Americas or the Middle East.

The patterns are consistent, and all too familiar. Truths dismissed as falsehoods. Propaganda and gaslighting embraced as truth. Peaceful protestors attacked. Journalists vilified. Experts undermined. Justice systems politicized as tools of autocracy rather than equality. Human rights jeopardized. The voices and votes of too many suppressed, or, simply, uncounted.

All of these egregious violations not only foment inequality, but share a common factor: impunity.

Through eight decades of work around the world, we at the Ford Foundation have seen how impunity—unjust action without consequence—erodes institutions, and permits and perpetuates corruption, all while exacerbating inequality. We’ve borne witness to the ways in which a lack of accountability undermines the rule of law.

For years, scholars and experts have warned that American institutions are not immune. Many have sounded—and are sounding—the alarm about the impunity with which norms have been pushed aside in the pursuit of unchecked power and the dangers of “democratic backsliding.”

To be sure, American history is rife with injustice. But I have always believed that we were pushing towards progress—however unevenly and incrementally. As an avowed optimist, I never quite grasped—until recently—what it could mean for extreme impunity to become a wrecking ball to the America I love. At the time, perhaps, it was my shortfall of empathy or imagination; now, to not recognize our vulnerability is simply delusion.

For when we look to our leaders in challenging times, we assume they will rise to those challenges. We expect that given the responsibility and opportunity, a person’s character and values prevail. We hope that some sense of common good or decency, honor or shame, might awake their better angels, compel them to look past their cynicism or self-interest, even shake them from their silence.

To me, that we have fallen this far points to a failure of moral leadership.

And by moral leadership, I do not mean the kind that moralizes; we don’t need self-righteousness, but selflessness. I don’t claim any special access to moral principles, nor mean to suggest the primacy of any kind or class of individual. I do believe, however, that in every theater of our lives, we need more people focused on the bigger, broader objective beyond the next earnings call or election: a long-term vision for a more just society. We need leaders who are motivated by values and incentives and outcomes that transcend those offered by the systems which, by design or neglect, have widened inequality to an untenable degree. We need new profiles in courage—more business leaders who serve the interests of all their stakeholders, not only their shareholders; more elected officials who serve a common good, not only the donors and partisans who comprise their base of support.

We need these leaders, not only for ourselves but for others. After all, right now, the world watches and wonders whether America can live up to its promise as a champion of human rights and a beacon of liberty and justice for all.

To be sure, America’s leadership crisis is far from new; like inequality, it has only been made excruciatingly plain during recent months and years. It is not even the first time I have spoken about moral leadership. It will likely not be the last because this crisis of moral leadership cuts across every issue.

Every one of our ongoing crises has been compounded by choices made and not made. Choices that deny humanity and dignity and justice to others on a daily basis, whether they take the form of active harm or passive neglect. Choices that, in an era of impunity and inequality, yield no consequences for the powerful, and too many for everyone else.

In this way, moral leadership—of all kinds, in every movement and institution, organization and community—is a prerequisite for positive change. And my continued hope comes from my faith that we can turn the tide, as we have before. To paraphrase Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, we can channel our mourning into a movement, our pain into purpose.

If our heroes could step up to meet their moments, so can we. If John Lewis and Ruth Bader Ginsburg could—if Fannie Lou Hamer and Shirley Chisholm could—we can too. And we must.

A vision of absolute equality

Six years after Lincoln asked whether democracy can long endure, four years after the test at Appomattox, Frederick Douglass offered a vision for not just endurance but transformation. As historian David Blight writes in his Pulitzer-Prize-winning biography of Douglass, in 1869, he traveled the country, delivering perhaps the most remarkable of his orations, Our Composite Nationality.

Douglass proposed the terms and tenets of a multiracial, pluralist democracy that would feel familiar, if still aspirational today: an antidote and antithesis to the division of the last several years; a more perfect, more inclusive, more hopeful future.

Douglass said: “We have for a long time hesitated to adopt and carry out the only principle which can…give peace, strength and security to the Republic, and that is the principle of absolute equality.”

That principle—and his vision—must inspire us now to act.

The future may feel uncertain. But the only real certainty is that, if we do nothing, we lose the fight for “absolute equality.” And when the world feels out of control, we must remember that we control whether or not we act.

That starts with voting. For as Douglass himself once put it, failing to vote is “as great a crime as an open violation of the law itself.”

And while voting is necessary and imperative, it, alone, is not sufficient. No matter the outcome of any election, our work remains clear.

We must hold our leaders accountable, and we must hold each other accountable, as well. We must break the vicious cycle of corruption, impunity, and cynicism—and demand better incentives for better leadership. We must continue to participate and engage, to show up and take action, because the fate of democracy is not decided any one day.

As Justice Ginsburg once wrote of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s moral arc of the universe, it will only bend toward justice with “a steadfast national commitment to see the task through to completion.”

We must constantly renew our steadfast commitment. We must see the task of justice through to completion, knowing that for our most vexing problems, the reward of our work may come for the next generation, or the one after that.

Once again, we are, as Lincoln suggested at Gettysburg, facing a great test. But with moral leadership, we can and will pass it. With moral leadership, this can and will be a moment, in Lincoln’s words, for “a new birth of freedom”; an opportunity to rebuild, more perfect.