Despite similar crime rates, the US incarceration rate is more than five times that of comparable countries. Out of every 100,000 Americans, 693 are in prison—a number that has multiplied in the past four decades. With both incarceration and recidivism rates at shockingly high levels, many wonder, What can be done?

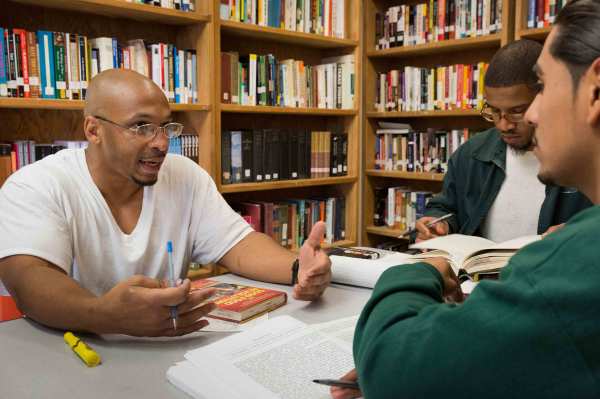

Ellen Condliffe Lagemann, former dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, explores one option in her new book, Liberating Minds: The Case for College in Prison. Langemann argues that educating people in prison is actually part of building a democracy. When incarcerated people have access to education, the benefits—including increased levels of hope, decreased recidivism rates, increased employment opportunities, giving back to communities, and stronger relationships with family members—ripple widely both inside and outside correctional facilities.

Recently, Lagemann—along with Anthony Annucci, acting commissioner of the New York State Department of Corrections, and Dorell Smallwood, graduate of the Bard Prison Initiative and youth advocate at Brooklyn Defender Services—took part in a panel discussion at the Ford Foundation about the critical role of education in the incarcerated community. Following are some highlights from their conversation.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

What we mean by education for all

To Lagemann, democracy is more than a political structure; it’s a way of understanding how we interact with each other. And so we cannot claim to be a democracy when a significant portion of our population is behind bars, without basic rights. Democracy and education go hand in hand: For the millions of men and women who are locked out of society, education is the only way they can participate in society—while in prison and once they are released.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

Education can help break the cycle of incarceration

Many point out that the US prison system doesn’t address the deep systemic issues that lead to criminal behavior—issues like poverty, lack of opportunity, and racial discrimination—and that our system is not truly rehabilitative. Incarceration has a profound impact on entire families, in ways that go beyond the specific period of incarceration: Children of people who have gone to prison are much more likely to go to prison than children of people who haven’t. Education helps break the cycle, connecting incarcerated students with the kinds of opportunities and insights that enables them to help themselves, their families, and their communities.

High-quality educational opportunities in prison also lower repeat crimes. For incarcerated men and women who participate in the Bard Prison Initiative—which offers them the opportunity to earn a Bard College degree while serving their sentences—only 2 percent of graduates return to prison, and 75 percent are employed within a month of their release. In comparison, the national recidivism rate is roughly 50 percent.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

Challenging perceptions about what incarcerated people need and deserve

College-in-prison is not universally embraced, and an immediate challenge is one of perception. Questions and criticism abound, rooted in the stigma we so often attach to people with criminal records. Some wonder: Is access to free education really something that this population deserves?

Smallwood and Commissioner Annucci agree that empathy matters—indeed, the best antidote to stereotypes and oversimplification is showing that incarcerated people are as real and complicated as anyone else. In his experience, Commissioner Annucci explains, incarcerated students are eager to learn and appreciative of the opportunity—one that prepares them to be better citizens when they return to their communities. And that benefits everyone. According to Lagemann, prisons are schools for crime, but they must become schools for citizenship.