Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnOn May 17 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, more than 100 sex workers converged on their state capitol to advocate for the idea that no job should lead to jail-time. Amid the besuited politicians of one of the reddest states in the country, 113 sex workers, wearing T-shirts that read “Sex Work Is Political,” testified for three hours about their experiences with the criminal justice system, and in support of a bill that would go farther in decriminalizing sex work than any other state-level legislation to date.

This piece is part of our featured series, The Story of the South is the Story of America.

All of the workers testifying that day—at significant personal risk—were part of an organizing campaign run by Women With A Vision (WWAV), Louisiana’s pioneering and premier public health organization and a Ford grantee. And while the bill didn’t pass that day, WWAV still considered it a victory, for having pushed the conversation forward—another small step towards radical change for a group that’s worked on issues others would not touch for the last 32 years.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnOver the last 30 years, Women With A Vision has operated out of a modest house in New Orleans’ Sixth Ward while becoming a powerful force for women of color across the South.

“I don’t think most people know how big our work really is, and the things we’re willing to do that most people aren’t,” said Deon Haywood, a cofounder of WWAV as well as its executive director.

With just 11 team members, the group helped lead the defense of abortion rights in Louisiana amid the Supreme Court battle in June Medical Services vs. Russo, when a draconian law threatened to close two of the state’s three abortion clinics. They fought to overturn a 200-year-old law that made survival sex workers register as sex offenders, and won. They registered thousands of marginalized Louisiana residents, including the young, elderly, and formerly incarcerated, to vote for a record-making 2020 election. And for more than three decades, they’ve fought the HIV epidemic in a demographic long overlooked by public health campaigns.

While the range of issues WWAV works on is wide, it’s all connected within the organization’s guiding Black feminist framework: recognizing that women of color and LGBTQ+ people have been the primary targets of the war on drugs and crime; that Black women’s lives are often effectively criminalized; and that solving most individual issues requires seeing how they intersect.

Deon Haywood

WWAV’s work didn’t start out quite so broad. Back in 1989, WWAV was an all-volunteer effort founded by a group of Black women working in social services, concerned that their demographic was becoming the fastest-growing population affected by HIV/AIDS.

“We thought, if nobody is addressing this in the African-American community, then we need to do something,” Haywood said. “We had an idea of what women’s health could look like, that true public health would help people understand the conditions in which they live, and give them access to do something about it.”

Kathleen Flynn

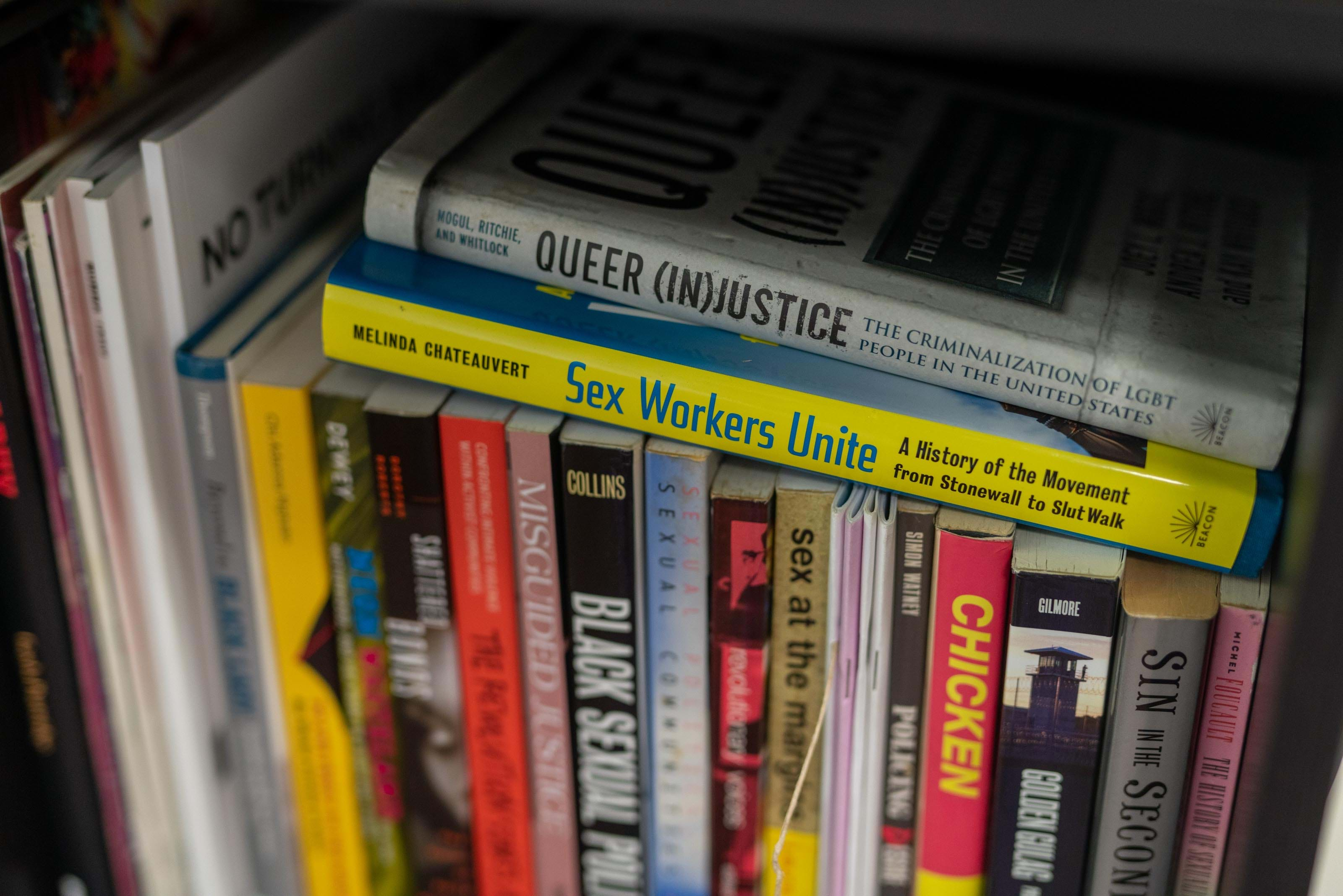

Kathleen FlynnAs Deon Haywood and her cofounders began to expand Women With A Vision, they created an intersectional framework for the organization grounded in their experience as Black women and Black feminists.

They started out working from an RV, guided by the principle of meeting their clients where they were, and letting the people “tell us what they thought they needed.” For its first 15 years, WWAV—which formally incorporated in 1991 and brought on Haywood as its first full-time employee in 1994—focused primarily on HIV prevention and education, reproductive justice, and harm reduction for substance users in their community. But after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, they realized a larger framework was necessary.

“Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, but it was the system that failed us, like the levees,” Haywood said. WWAV saw the same sort of systemic failures all around them—in policies that entrapped women, drove incarceration, punished the vulnerable, and did little to address root problems.

“We realized that we were going to need an executive director who could be on the ground, taking our work further. And that became me,” said Haywood. “And I realized that I had to get involved in changing what that looks like. We couldn’t just keep serving people without making change. We had to put our feet in these policy waters to change the laws affecting people’s lives.”

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnDecriminalizing sex workers became one of WWAV’s top priorities recognizing that both survival or chosen sex work is inextricably tied to race, economic realities and sexual identity.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnWhat sets WWAV apart is its commitment to meeting marginalized women where they are and working together to get to the root of the problem. “Change always comes from the people,” Haywood said.

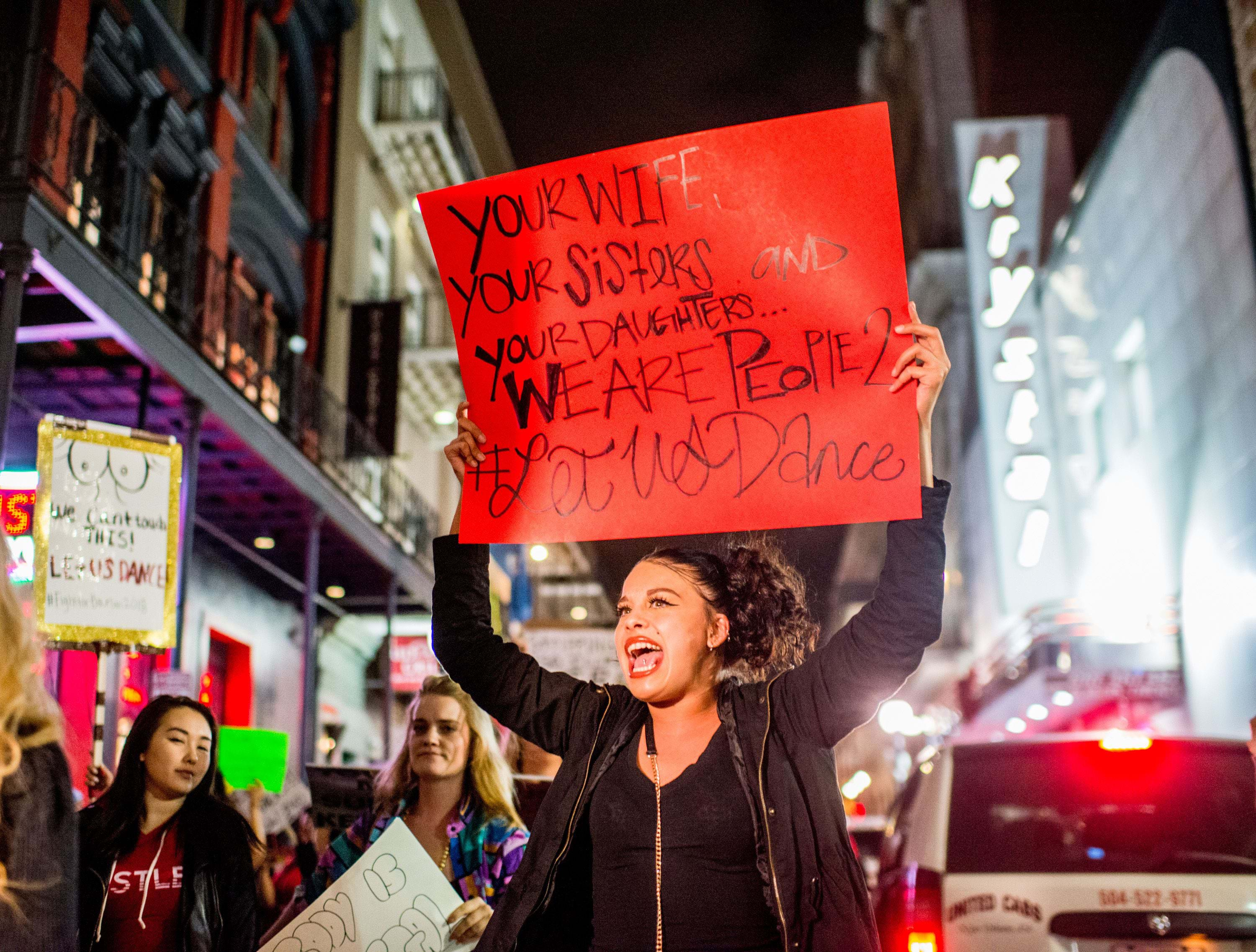

One of the first issues Haywood and her team set to tackle was the increasing criminalization of sex workers and the linked increase in violence targeting Black trans women. WWAV had always worked closely with sex workers in New Orleans, recognizing that both survival or chosen sex work is inextricably tied to economic realities. “Sex workers are mothers, daughters, and caregivers,” Haywood said. “And they’re also the working poor. Because we’re unwilling to give people a living wage in this country, some people have decisions to make about their survival, and they do so. And they should not be criminalized for that.”

WWAV recognized that any time reproductive and sexual behavior is criminalized, Black women suffer the most. Whether abortion, sex work or contraception, Haywood said, “Anytime a law is attached to any of these—where if you get them or do them, you could serve time—we know it will end up being Black women, Black people, Black trans people and gender-nonconforming people. We are always at risk with the worst that can happen with the law.”

And indeed, around 2008, WWAV staff began to notice that some of their regular clients would disappear for weeks at a time, only to reemerge and say they’d been arrested for “Crimes Against Nature.” The charge was based on a 200-year-old law, originally written to criminalize gay men, used at police and prosecutors’ discretion to levy harsh, felony-level penalties against sex workers beyond the state’s anti-prostitution laws. Those convicted—the vast majority of whom were Black women—not only faced steeper sentences and fines, but also were placed on the sex-offender registry for 15 years to life. They had the words “sex offender” printed on their driver’s licenses and were required to send postcards to their neighbors. They subsequently struggled to find housing or jobs, were blocked from homeless shelters and lived in fear of violent attacks. When WWAV started working on the issue, almost half of all registered sex offenders in Orleans parish were women arrested for sex work.

EMILY KASK/AFP via Getty Images

EMILY KASK/AFP via Getty ImagesOne of WWAV’s biggest moments came in 2013 when it fought to restrict the implementation of Louisiana’s 200-year-old law, originally written to criminalize gay men, that levied harsh, felony-level penalties against sex workers, and helped remove 800 people from the sex offender registry.

“That was the ‘click’ for us, that OK, we’re going to fight this,” Haywood said. “We wanted to give a face to those women.” WWAV’s “NO Justice” campaign was born. They filed a class-action lawsuit challenging the Crimes Against Nature statute with their legal partners; urged lawmakers, judges and prosecutors to remove the statute from the books or stop applying it; and conducted community outreach to explain why the violation was a breach of human rights. While the law wasn’t completely withdrawn, lawmakers restricted its implementation. And in 2013, WWAV resolved its class-action suit with the victory of removing 800 people convicted of sex work from the sex offender registry.

Christine Breland Lobre

Soon after the organization completed its “NO Justice” campaign, Christine Breland Lobre, now WWAV’s program director, came on board, driven by a desire “to learn about dismantling oppressive systems.” In the wake of WWAV’s successful challenge of the Crimes Against Nature statute, the American Bar Association asked the group to craft a new court diversion program to help sex workers avoid incarceration. That program, Emerge Crossroads Diversion Program, became Lobre’s focus.

“We didn’t want it to be your standard program, where it creates more obstacles and barriers in a person’s life, and becomes a sort of layaway program for future incarceration, which a lot of diversion programs do because they don’t take the whole person into account,” Lobre said.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen Flynn“If I have a vision for the South, it’s liberation,” Lobre said. “That sounds sort of starry-eyed, but I mean it. This is my home, and I love it, with all of the flaws that come along with it.”

No matter the issue, WWAV’s approach has always been one of harm reduction. “We wanted to be extremely intentional that there would be no fines, no fees, no drug urinalysis, and no cookie cutter programs,” Lobre said. “We wanted to make sure that we were meeting people where they are, identifying their goals and hoping to link them to resources so those goals can be achieved.”

Emerge launched in 2014 and quickly earned the backing of local judges, who embraced WWAV’s model and made efforts to treat sex workers with dignity. The judges began to hold dedicated sessions to handle workers’ cases separately from the rest of their court docket, used correct names and pronouns for trans defendants, and worked with prosecutors to drop charges after the diversion program was completed.

In time, Lobre ended up bringing these programs—as well as others for parenting, trauma, or substance abuse—into local jails to help address what had long been a gap in services between men’s and women’s correctional facilities. Today much of Lobre’s advocacy around sex work focuses on decarceration efforts, including bail reform and shifting law enforcement practices from arresting sex workers to issuing citations—a major change that mitigates the most catastrophic effects of arrest and incarceration.

“We’ve gone from folks being arrested and staying in jail for a solicitation prostitution charge to folks either being left alone by law enforcement or just given a summons or a citation. That still means you’re court-involved, but it doesn’t take you out of your family or community in that instant,” Lobre said. And in that way, “We keep chipping away at the carceral state.”

“At the end of the day, WWAV is like an octopus with 100 arms,” said Lobre. “We’re so small, but we touch on so many different areas and work in conjunction with so many other organizations, in our state and across the nation. And the tide is very, very slowly turning.”

Michelle Wiley

Putting Emerge and other WWAV programs into practice is the work of case manager Michelle Wiley, who builds close, one-on-one relationships with both clients and members of the broader community.

Wiley, a Mississippi native who moved to New Orleans 12 years ago, joined WWAV in 2014. Her job can look very different from one day to the next. Some days it’s training staff at a local barber shop on how to administer life-saving overdose medications like Narcan. Other days it’s walking to homeless encampments to distribute clean needles and kits for substance users. And sometimes it’s just sitting in WWAV’s backyard garden with clients to talk about their lives.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnAs a case manager for WWAV, Wiley’s entire role is built around relationships. She establishes trust and understanding with the organization’s clients and embeds herself in the communities it serves across Louisiana.

Respecting the rights of WWAV’s clients, Wiley doesn’t try to talk them out of sex work. “We sit and talk about life and, if there’s something they need help with, I help them,” she said. “But there’s some that say, look, I’ve been doing this all my life, this is my living. I can’t get a job, I’ve got a felony on my record.” In those cases, helping means just offering a safe place. “I tell the young women, just come here, it’s home here. We don’t judge, they come in, and we’ll all order up some Chinese.”

That lack of judgment has allowed WWAV to serve as a vital lifeline for its most vulnerable clients, including LGBTQ+ youth and Black trans women, some of whom turn to sex work to survive in a state where they can still be legally barred from employment and housing, and are often subject to violence. Many are left living in abandoned housing around New Orleans or on the streets; sometimes Wiley even finds clients sleeping under WWAV’s offices.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen Flynn“Black women, Black people, Black trans people and gender-nonconforming people—we are always at risk with the worst that can happen with the law,” Haywood said.

Occasionally, that level of precarity leads to tragedy. In the last few months, Wiley nearly lost one client to violence. A trans sex worker, who also did part-time harm reduction work for WWAV, was shot multiple times in an anti-trans hate crime. The client was left paralyzed; her attacker was let go. Over the same time period, Wiley saw another client, a young Black lesbian estranged from her family over her sexuality, lose her life to an overdose.

“I was destroyed, our office was destroyed over that,” she said. “It’s hard. I’m in a close family, especially with the community. But we hold a lot. We hold a lot.”

Jenny Holl

It’s been 32 years since WWAV was founded to address HIV/AIDS among Black women. While the epidemic doesn’t look the same in many parts of America, in the South it’s only grown. Today the region accounts for more than half of new HIV cases each year. In 2020, Baton Rouge and New Orleans, respectively, had the first and third highest HIV infection rates of all US cities. Nationwide, Black Americans are disproportionately affected, accounting for around 42 percent of new cases. Because of that, HIV prevention and education remains one of WWAV’s flagship programs.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnThe South accounts for more than half of America’s new HIV cases each year. Holl, a WWAV program manager, will tell you ending the epidemic is only part of the challenge in a region where HIV and AIDS are still highly stigmatized.

Jenny Holl joined WWAV in 2018 as its Ending the Epidemic program manager and began working closely with Louisiana’s Department of Health to help make the state’s outreach community-driven. In particular, Holl said, WWAV took the lead in rural areas, which are in danger of being left behind in a state with extremely limited sex education, and where teachers are often prohibited from even acknowledging non-heterosexual sex.

Holl started with a series of community conversations, talking to different stakeholders across Louisiana. “A lot of what we heard came back to education,” she said. “But everything really came back to stigma. People don’t want to talk about HIV, and a lot of people still have a lot of harmful beliefs.”

Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesThe goal of the group’s HIV/AIDS work today is to educate populations that don’t believe themselves to be impacted and help them understand how closely the epidemic is related to other systemic issues, such as racism and discrimination in housing and employment.

In rural areas, Holl said, there are providers who still profile people to decide whether they need to be tested for HIV or receive the preventative medication, PrEP. “We have clients who’ve gone to physicians who won’t see them because they have HIV or put on double gloves,” she said. “There are even people, particularly within smaller towns, who have had their information shared—essentially being outed, which in these areas, where HIV is so heavily stigmatized, can be really dangerous.”

Ending the Epidemic’s goal today is to figure out how to carry educational and prevention programs forward, particularly in populations that don’t believe themselves to be impacted. Currently, Holl is working to normalize HIV testing among both community partners and providers, and find non-traditional partners, from faith-based organizations to food pantries, to help distribute information and offer testing. But, she says, a goal for WWAV is also helping people understand how closely the epidemic is related to other issues.

“There are many different movements gaining traction, particularly around HIV and public health,” she said. “But so much of what needs to change is about bigger, structural issues, and finding a way to bring those different movements together and work towards a common goal. So that’s where we’re at right now: trying to align ourselves with others and understanding that a lot of what is driving HIV in Louisiana right now is racism, discrimination against LGBTQ+ people, discrimination in housing and employment.”

Raven Frederick and Elyse Degree

In 2020, Louisiana registered more people to vote than at any time, in at least the last 20 years. And when polls opened, the state saw record numbers of early voters. In part, that’s thanks to WWAV and its “Envision Change” voter engagement program launched in 2016 under Raven Frederick, community outreach specialist.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnDegree works hand in hand with Frederick to engage communities that have historically been unregistered or infrequent voters and help them realize the power of their vote.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen Flynn“We don’t mind going to the areas where nobody else wants to go,” Frederick said. “That’s why WWAV is so important: we are the organization going to meet the people where they are.”

WWAV’s get-out-the-vote work includes everything you might expect: phone banks, door-to-door canvassing, education campaigns, and, in 2020, digital billboards on roadways across Louisiana. Taken together, these efforts registered around 10,000 people in the 2020 election cycle, while also operating under intense conditions, as Elyse Degree, WWAV’s voter engagement data coordinator, points out. “During hurricane season, our canvassers were working with no lights, in the cold, with no electricity. But they were out here making phone calls, hitting the ground during the presidential election.”

Emily Kask / AFP

Emily Kask / AFPWWAV registered around 10,000 people across Louisiana in the 2020 election cycle. That year, the state registered more people to vote than at any other time in at least the last 20 years and saw record numbers of early voters.

But where WWAV stands out is its focus on helping marginalized people, particularly low propensity Black women voters, to access their right to vote.

“We don’t mind going to the areas where nobody else wants to go,” Frederick said. “We go under the bridge and talk to the homeless. We go into jail and talk to people behind a wall. Or into the nursing homes, to help elderly people change their voting locations. That’s why WWAV is so important: we are the organization going to meet the people where they are.”

One of the populations WWAV works with a lot is formerly incarcerated people who may incorrectly believe they’re ineligible. “You have some people that are just coming back into society and the first thing they tell you is that you can’t vote—which is not true,” Frederick said. “As long as you’re not on papers—on parole or probation—you have a right to vote.”

“In the past year, people really came to understand the importance of what it is to vote. We’ve seen how a lot of Southern states have changed, and how people were able to mobilize in areas where they haven’t shown up like they did in this election. I think people’s perception has really changed towards voting.”

To Degree, it’s just more proof that the holistic approach of Black women’s organizations can “get things done.” “Organizations like WWAV show people that we’re able to take the little that we have and make a lot. We take the small lemons we have and make big lemonade.”

Lakeesha Harris

Lakeesha Harris wears many hats as WWAV’s director of reproductive health and justice. She talks with legislators, crafts educational materials, and advocates on behalf of abortion rights, maternal healthcare, and sex worker decriminalization. In 2020, she led WWAV’s intervention in the June Medical case that reached the Supreme Court, vying to keep Louisiana’s few remaining abortion clinics open. Under Harris, WWAV continues to lobby and testify in support of abortion rights in the state capitol, and is working with partners in neighboring Mississippi—which just moved to overturn Roe v. Wade—to develop a new amicus brief for the latest abortion ban destined for the Supreme Court.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen Flynn“We all know that the South is conservative,” Harris said. “But we’re not just fighting a political landscape. We’re fighting an environmental landscape where people have been forgotten about, that is toxic, and where our political leaders don’t care about us.”

That’s vitally important for a number of reasons. For one, Louisiana and Mississippi consistently rank as the top two states for maternal mortality. (“It’s a contested title,” Harris said grimly.) One of the reasons for that is the lack of quality maternal care in many areas, forcing women to travel long distances for routine checkups, emergency visits and deliveries. Even greater obstacles are in place for abortion, both in Louisiana—where the remaining three abortion providers struggle to keep up with demand—and Texas and Mississippi, where numerous abortion clinics have been regulated out of business in recent years. All of these obstacles make the region ground zero for abortion rights in America.

“We’ve been fighting for a very long time,” Harris said. “And the fight is ongoing.”

On top of her work to protect abortion rights, Harris helped lead the organization’s push to decriminalize sex work. Her and the team enlisted current and former sex workers to envision a full decriminalization bill. They also supported the development of a Sex Worker Advisory Committee, which operated autonomously from WWAV, but helped the organization raise public awareness. Then came May 17, when 113 sex workers converged on the capitol for three hours of groundbreaking public testimony.

Kathleen Flynn

Kathleen FlynnHarris knows the fight for reproductive justice isn’t isolated to her state or even the South. In 2020, she led WWAV’s intervention in a case that reached the Supreme Court in 2020, helping to keep Louisiana’s few remaining abortion clinics open, but is now working with partners in neighboring Mississippi, which just moved to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Among the speakers was Harris’s daughter, who had been arrested in Jefferson Parish for sex work. “I never wanted her to feel ashamed of her labor or to feel threatened,” Harris said. “I wanted her to feel powerful in the decisions she made. And for her to provide testimony—even though she was scared, and had been targeted and incarcerated—it was very powerful.”

It reaffirmed for Harris why she does the work she does. “I do it because it’s true. The personal is always political. I’m not working with outside people—I’m working with people I know, love, care for; people who are my family and community members.”

Sometimes, Harris said, doing this work in the South can feel like going up against insurmountable odds. “We all know that it’s conservative,” she said. “But we’re not just fighting a political landscape. We’re fighting an environmental landscape where people have been forgotten about, that is toxic, and where our political leaders don’t care about us.”

Driven by her Black feminist perspective, she always looks for the connections between different issues when fighting for justice—whether it’s addressing the exponentially higher rates of maternal mortality that Black women face, targeted assaults on Black, queer and trans people, or the lack of a livable minimum wage for essential workers forced to work during a pandemic.

“That is the landscape we find ourselves in in the South and the Deep South, in particular,” she said. “It can be all-encompassing. Sometimes it can really rock your world. But the people who are fighting back are doing so under deep oppression themselves, and they are phenomenal and brilliant, and are knocking all of these barriers down, piece by piece.”