The COVID-19 pandemic and the accelerated movement for racial justice have called into question many philanthropic practices. But one practice that had been increasingly receiving interest in the past two years deserves continued attention: participatory grantmaking, the practice of involving community members and other stakeholders in the grantmaking process. As I am learning through my own efforts to practice this, it can lead to different—and I would argue, better—decisions about who and what to fund. Funders ceding power over grant decisions is relevant now more than ever given the momentum of movements for justice.

At Ford, we are in the beginning stages of exploring this model. In 2015, our former colleague Susie Jolly engaged with the topic in our China office. In 2017, to determine the efficacy of participatory grantmaking for an institution like ours—global, multi-issue, and not tied to any particular place or identity group, we commissioned a monograph by Cynthia Gibson, entitled “Participatory grantmaking: has its time come?,” and in 2018, supported a GrantCraft guide on this topic. More recently, we have used grantee consultation and co-creation workshops to develop initiatives like the BUILD developmental evaluation. And currently, the Disability Inclusion Fund housed at Borealis Philanthropy, which we helped seed, uses a participatory approach in its grantmaking.

Given this relatively limited background, we wanted to help increase knowledge about different dimensions of participatory grantmaking—while also trying it out more ourselves.

In 2019, we commissioned nine research projects that would build the evidence base about participatory grantmaking. And we chose the projects using a participatory process, described further below.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we reached out to the research teams to see how they were doing. It was heartening to hear that they remain committed to their original plans, with findings scheduled in early-to-mid 2021.

The products of the research are forthcoming, but given the increased interest in participatory practice (for example, as documented in an Inside Philanthropy survey of foundation program officers), this is a good moment to reflect on the participatory process by which we selected the projects, and to give the research teams the opportunity to share more about their work.

About the selection process—from our perspective

Working with consultant Cynthia Gibson, we sought those interviewed for the monograph and GrantCraft guide to identify a steering committee of 10 individuals: three participation experts, four participatory grantmakers, and three members of the target audience of national and global foundations (including myself). Our group of 10, with Gibson as facilitator, was responsible for selecting the research projects through a request for proposals.

But more than that, our group had an active role in shaping the direction of the effort. We clarified the theory of change, wrote and disseminated the request for proposals, reviewed the proposals, and made grant recommendations, based on which I then invited a set of nine projects to receive Ford Foundation funding.

As I look at the list of projects chosen, I have to say that on my own, I would have made different choices. It would not have occurred to me to expand the target audience from national and global foundations to individual mega-donors, which one of the projects ended up working on. Also, I likely would have weighted the mix more toward studies that focus on how grant outcomes differ in participatory processes.

And that’s the point: the mix of projects corresponds more closely to what the field really wants and needs. So what I might have wanted on my own matters less than that.

What therefore emerged from this process was a set of research projects that map current philanthropic practice on participatory grantmaking; offer toolkits for individual donors and foundations to begin embracing the practice; and document the experiences and lessons learned of longtime participatory-grantmaking institutions.

About the research projects—in their own voices

The questions the projects investigate are especially relevant in 2020, when rapid response and emergency funding can mean that urgency wins out over inclusion. But as the perspectives below reveal, this is a false dichotomy. Indeed, what is especially urgent is for funders to do a better job including the grantees and communities we seek to serve in our decision making, and when possible, turning over that power to them.

So, research teams: what is your project, and why, in this moment, does participation matter more than ever?

Colton Strawser, Assistant Professor of Philanthropy at the University of Texas at Arlington

I am studying how community foundations are practicing community leadership and engaging local people in crafting foundation strategies—including grantmaking. Community foundations are a catalyzing force for local change. With most areas of the United States being served by one or more community foundations, there is an important need for them to create more spaces for residents to envision their community. This research seeks to gather perspectives from community foundations implementing community leadership agendas as well as advice they would have for their peers.

Evans School of Public Policy & Governance at University of Washington: David Suárez, Kelly Husted, and Emily Finchum-Mason

We are conducting a nationwide survey of 500 of the United States’ largest private and community foundations (by total assets) that examines the scope of participatory approaches to governance and grantmaking. This work seeks to understand the diversity of participatory approaches currently used in the philanthropic sector, the perceived benefits and challenges of incorporating participatory approaches, and the ways in which participatory outcomes are evaluated. This project is the first component of an ongoing research agenda that aims to systematically characterize how large foundations engage those they aim to serve.

This work comes at a time when some critique philanthropic foundations as plutocratic and undemocratic. Furthermore, the confluence of COVID-19, the subsequent economic downturn, and the fight for racial justice have cast a spotlight on long-standing power asymmetries in U.S. society. Participatory approaches to grantmaking hold promise in terms of democratizing the practice of philanthropy, increasing equity, and shifting power from elite foundations to marginalized communities. More research needs to be done to understand the extent to which foundations currently utilize these participatory approaches and how to translate their experiences into meaningful action.

Urban Institute Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy

We are investigating how the method and processes of deliberation impacts the grants that participatory foundations make. Our focus is on participatory philanthropy programs in large foundations whose missions are to support social justice or power building in local nonprofits. Within that group of foundations, the center’s research is looking to better understand the relationship between the deliberation method and the grants participatory programs make.

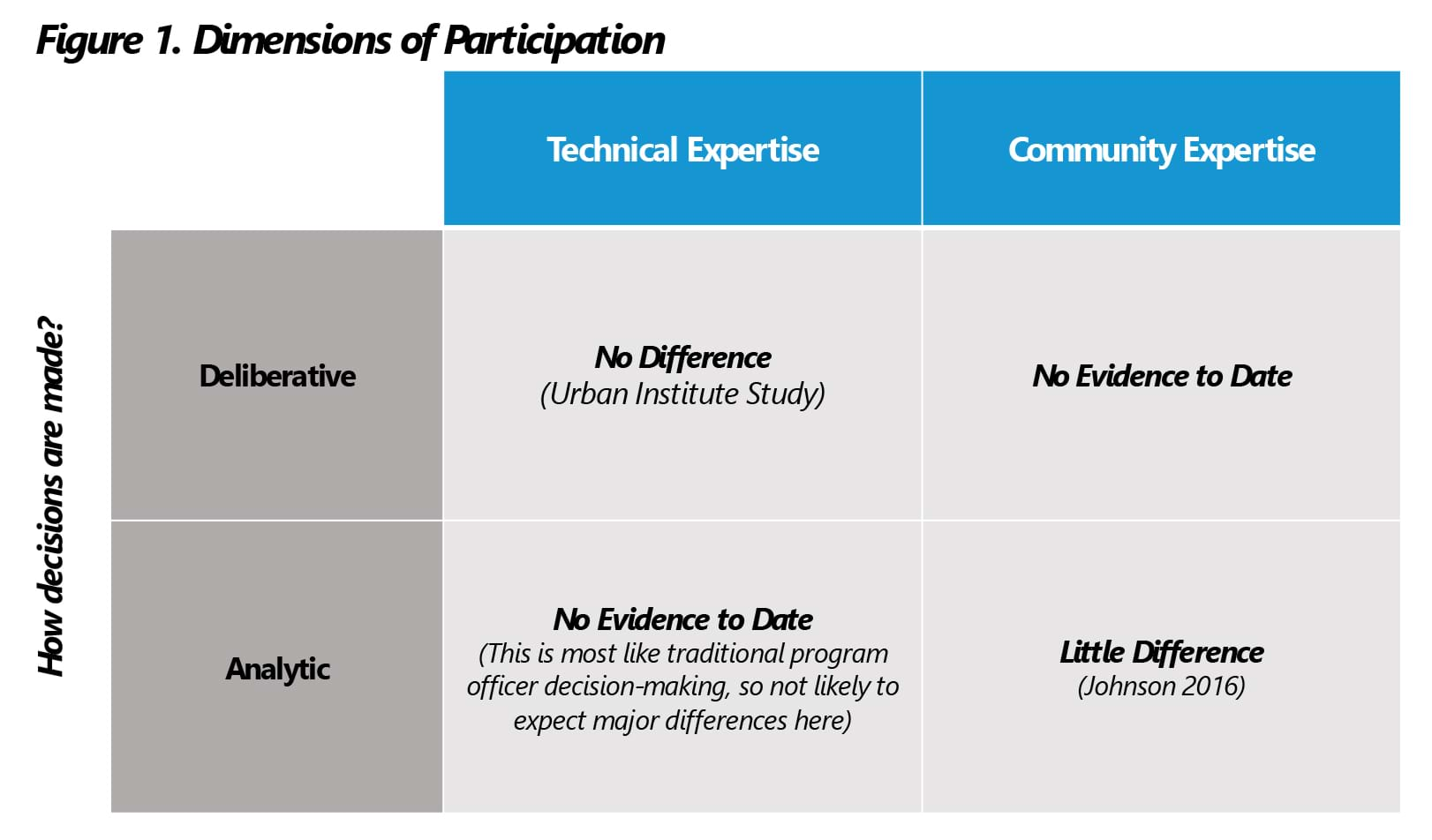

Figure 1 describes existing research and what we currently understand about the deliberation method and grant decisions.

There have been studies that looked at deliberative participation (no scorecards used) with technical or expert grantmakers and there has been research on analytic (scorecards used) with community members/residents making grant decisions. Unfortunately there has not been research examining deliberative participation with community members/residents as decision makers. There has also not been research comparing the different ways decisions are made—i.e. comparing a deliberative and analytic participation process with grant decisions. Since we are in the beginning phase of our project we are open to studying either unanswered question.

Women’s Funding Network

The Women’s Funding Network is a community of gender and racial justice funders that grew out of the feminist equity movement in the 1980s, as an organizing power for place-based community foundations that fund through a gender-lens. Today, the network includes local women’s funds across the United States and in 11 countries, national and international funders, grassroots organizations and individuals. Through the network, WFN provides gender justice leaders and advocates with a variety of tools to help them succeed—from research and education, to strategic-led initiatives and events, to advocacy and unifying a collective, amplified voice.

Working with the women’s funds in the network, WFN engaged with the Ford Foundation to examine the participatory grantmaking practices of place-based women’s funds. As local funders, women’s funds have a long history of collaborative grantmaking practices that include the voices of those their programming aims to support, and with the cross-sector partnership of local stakeholders. This work lifted up the many ways in which women’s funds conduct their grantmaking, leadership, and advocacy work that include the principles of participatory grantmaking to involve all members of the community from donors, to educational institutions, grantee partners and the community members impacted by their funding and programming. Many women’s funds have an over 10-year history of intentionally applying these principles, and some are newer to the practices, but all of the philanthropic partners in this study do embrace a systems approach that centers the voices of individuals and communities they work to support.

In light of the COVID-19 health and economic crisis, along with the accelerated movement for Black Lives Matter and emphasis on racial justice, women’s funds have applied this year, more than ever, the flexibility and adaptability necessary in philanthropy to respond to the immediate need in their communities by shifting their grantmaking to operational dollars, and thus making room for grantees to provide the response where the community needs it most, and in setting up rapid response funds to disperse immediate funding to where their communities have identified emergency need.

The Women’s Funding Network is hopeful that philanthropy can build on the research that will come from this study, and follow the lead of these hyper-local “first responders” in philanthropy, to also center the voices of those most impacted by injustice and inequality and allow for community decision-making and sharing in the power that comes from these participatory practices.

Seattle University/Pride Foundation

Elizabeth Dale, assistant professor in nonprofit leadership at Seattle University, is studying how Pride Foundation, a LGBTQ+ community foundation working across five western US states, is shifting its grantmaking practice to both align with the organization’s racial equity core and include greater community participation in setting funding priorities and making grant decisions. She is documenting the culture-change efforts within the foundation and interviewing staff members, community and grantee organizations in order to provide a road map for other foundations that seek to adopt more participatory practices.

Pride Foundation CEO Katie Carter says, “Pride Foundation recognizes that all movements for justice are interconnected and that all of our identities shape our lived experiences. Involving community partners and organizations in grantmaking work is central to supporting a dynamic and diverse LGBTQ+ community, and this grant is allowing the foundation to undertake both the important personal and organizational work necessary as well as to hear directly from our community partners as to how they want to be involved in the foundation’s work.”

Philanthropy Northwest

The world has changed, calling us to action over research and surveys. We’ve shifted our grant focus to allow us to capture “learning by doing” and to encourage “participatory learning by funding” as we support the development of Philanthropy Northwest’s collaborative initiative around directing resources to dismantle anti-Black racism and shifting power to Black-led organizations. Through this grant, we are exploring how we can test, learn from and model for the field an approach to grantmaking that combines participatory practices with trust-based philanthropy, racial equity, The Giving Practice’s Reflective Practices and other emerging and community-based approaches. We are documenting learnings as we go and will share them in the form of blog posts and other written articles for publication that model how to engage in these practices and invite funders to engage with us as we work to develop and refine our approach. A collection of these learnings will form a toolkit or guide for funders to use to reimagine their own approaches to shifting power and decision-making in their grantmaking.

Disability Rights Fund (DRF)

In partnership with BLE Solutions and a research board of persons with disabilities, our project examines DRF’s more than a decade of experience as a participatory grantmaker operating in step with the disability movement’s slogan “nothing about us without us.” Specifically, we are assessing the link between participation of persons with disabilities at all levels of decision-making—in governance, grantmaking committee and among staff—and our effectiveness in enabling organizations of persons with disabilities to successfully advocate for rights. Our hypothesis is that having persons with disabilities in decision-making roles within the organization and, through grants, within the community, is the primary enabling factor in achievement of more than 240 national and local changes to legislation, policy and government programs to better support the rights of persons with disabilities around the world.

Participation matters now more than ever. Paraphrasing from a letter to the editor to the Chronicle of Philanthropy co-written by DRF Executive Director Diana Samarasan and philanthropy consultant Katy Love, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement have shone a spotlight on the precariousness of societies that value the lives and opinions of people who are wealthy (as well as those perceived as healthy) more than the lives and opinions of those who are not. When some are marginalized, everyone is at risk. In a recent global survey about the impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities, 84 percent of persons with disabilities in Uganda noted a lack of access to food, and 44 percent of women and girls with disabilities in Rwanda reported that COVID-19 stay-at-home measures have fueled gender-based violence. In this context, philanthropy needs to examine its own power dynamics and their impact on change (or lack thereof). Funders must not presume they know the solutions. Instead, they must not only ask people who are affected for input, but they must also cede money and power to those with lived experience.

Haymarket People’s Fund

Haymarket People’s Fund is an anti-racist, multi-cultural foundation committed to strengthening the movement for social justice in New England. Through grantmaking, fundraising and capacity building, we support grassroots organizations that address the root causes of injustice. Haymarket also organizes to increase sustainable community philanthropy throughout the region. More than fifteen years ago, Haymarket went through an organizational transformation process to become an anti-racist organization, and we feel it is time for a systemic participatory assessment of Haymarket’s grantmaking work. We are collaborating with researchers from Boston College and Harvard University to assess our grantmaking process and measure its influence on grantee organization’s anti-racist community organizing.

In line with participatory philanthropy, Haymarket is a values-driven organization that attends to process as much as outcomes and centers the voices of those impacted by systemic oppression. We seek evidence that a grantmaker with a longstanding commitment to participatory decision making and practices can promote anti-racist community organizing.

Haymarket has always fundamentally believed that participation of those most impacted is essential. This is now true more than ever. We hope to uplift this value and show through participatory research that participatory anti-racism grantmaking can have an impact.

New England Grassroots Environment Fund

The New England Grassroots Environment Fund, Inc, (Grassroots Fund) was founded in 1996 as a funder’s collaborative, with a mission to energize and nurture long-term civic engagement in local initiatives that create and maintain healthy, just, safe and environmentally sustainable communities throughout the six New England states. With the introduction of guiding values in 2016, the Grassroots Fund has been co-creating and deepening its comprehensive participatory decision-making process with frontline organizers, non-profit colleagues and funding partners. The core value underlying the process has been that lived experience is expertise. This is in contrast to relying on an “expert model”, where those with a certain background will always know best. The expert model can manifest explicitly, by requiring academic experiences/professional backgrounds, or more subtly and insidiously, through bias related to identity markers an expert “should” have, including gender, race/ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, etc.

With this fundamental approach, the Grassroots Fund is looking beyond whether participatory grantmaking adds value or promotes diversity, equity and inclusion. To us, there is no alternative and this is not a “choice” but a fundamental commitment to address the intersectional, intractable issues of climate change, inequity, food insecurity, etc. More on the Why of the Grassroots Fund.

Through this Ford Foundation grant, the Grassroots Fund is working with a consultant to explore the following questions to both inform their own grantmaking practices and to share with the broader philanthropic community to further participatory grantmaking practices (PG) across the field:

- What are the best evaluation strategies for ongoing adaptations using real-time feedback from participants necessitated by PG processes? How can we ensure we learn alongside frontline organizers on the strategies with greatest on-the-ground impacts in order to adapt and provide support in ways that reflect current reality and urgency?

- What are impacts of participatory grantmaking on all those participating – readers & grantmaking committee, applicants & grantees?

- How does that impact feed into opportunities to deepen in-person & virtual communities of practice to further collective learning and movement building?

Conclusion

I’m grateful to the research teams for their work, and for taking the time to share their perspectives and plans during a time of uncertainty for all of us. But I come away from their reflections more grounded than ever in the conviction that we must keep asking the question about the role of participatory grantmaking in foundation practice. A recent study by Dalberg of US foundations’ response to COVID-19, economic downturn, and the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans asserted that “these crises add weight to longstanding calls for philanthropy to shift practices and share power.”

Through the participatory process by which we selected these research projects, and from the future results of the projects themselves, we hope to continue learning about—and leaning into—these shifts in practice and power.