The Ford Foundation’s headquarters may be in New York City, and our work may span continents, but our roots have always been in the American Heartland.

We were born in Detroit in 1936, shaped from the industrial engine that created the American middle class. This isn’t just our origin story; it continues to guide our understanding of how progress builds: on shop floors, family farms, and main streets across America.

Over 90 years, we’ve grown to address challenges and narrow inequality wherever we find them. We have never stopped investing in the places that made us, sowing generational partnerships to ensure the Heartland remains a proving ground for the American Dream.

Our strategy is rooted in the stalwart conviction that local leaders must remain the architects of their own regional growth. We don’t impose solutions; we help the people who know their communities best build the scaffolding. This belief informs the three pillars that have guided us since our founding: stewardship, civic architecture, and democratic wealth-building.

The Bedrock of Stewardship

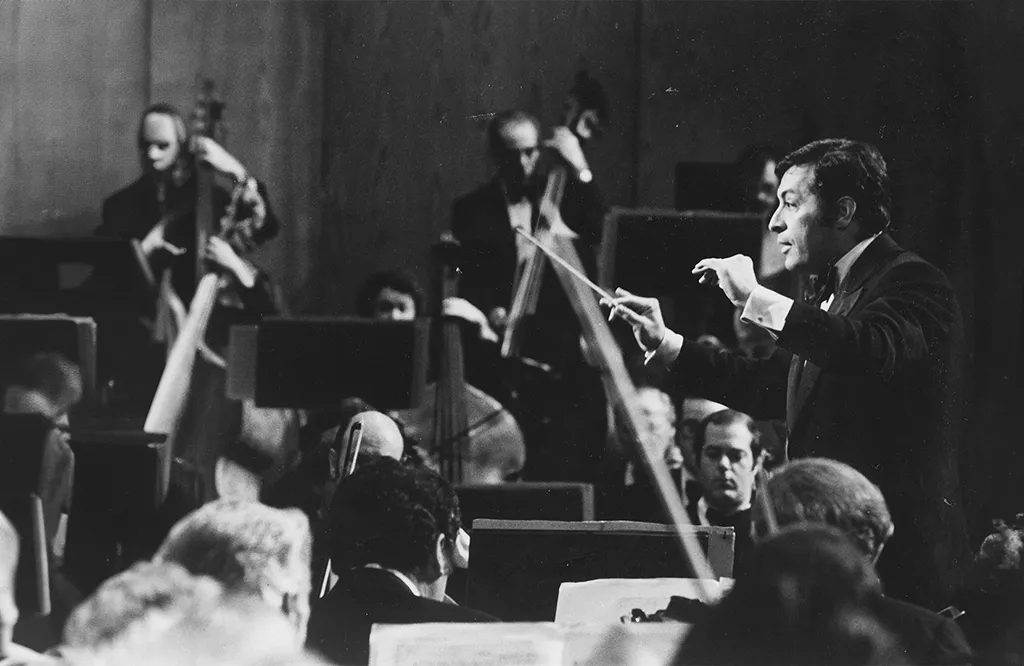

In philanthropy, there is often a temptation to chase the latest innovations or pivot toward trendy topics. Stewardship, on the other hand, is a long-term commitment to communities across decades, not just funding cycles. For Ford, this is personal: Since our founding in Detroit, we have been deeply committed to the city. Our aspirations are rooted in a history that spans supporting the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) in the 1940s to ensuring the city is prosperous, equitable, and sustainable today.

Stewardship means ensuring that a ZIP code is an asset to be passed down, not something to be escaped. We saw this most clearly in our role in Detroit’s “Grand Bargain.” In 2013, when the city filed for the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history, we didn’t walk away from our roots: We committed $125 million over 15 years to a coalition designed to protect municipal pensions and preserve the DIA. This wasn’t just about balancing ledgers—it was about honoring a social contract and protecting the people who built the city.

Stewardship is the quiet work of staying at the table when the cameras leave. It is the realization that a community’s resilience is built on the stability of its institutions. Whether it is a world-class museum or a neighborhood clinic, these are the anchors that hold people together during turbulence as well as tranquility.

Rebuilding Civic Architecture

If stewardship is the bedrock of a community, civic architecture is the system of roads and bridges above it, both literal and figurative, that enables people to solve their own problems.

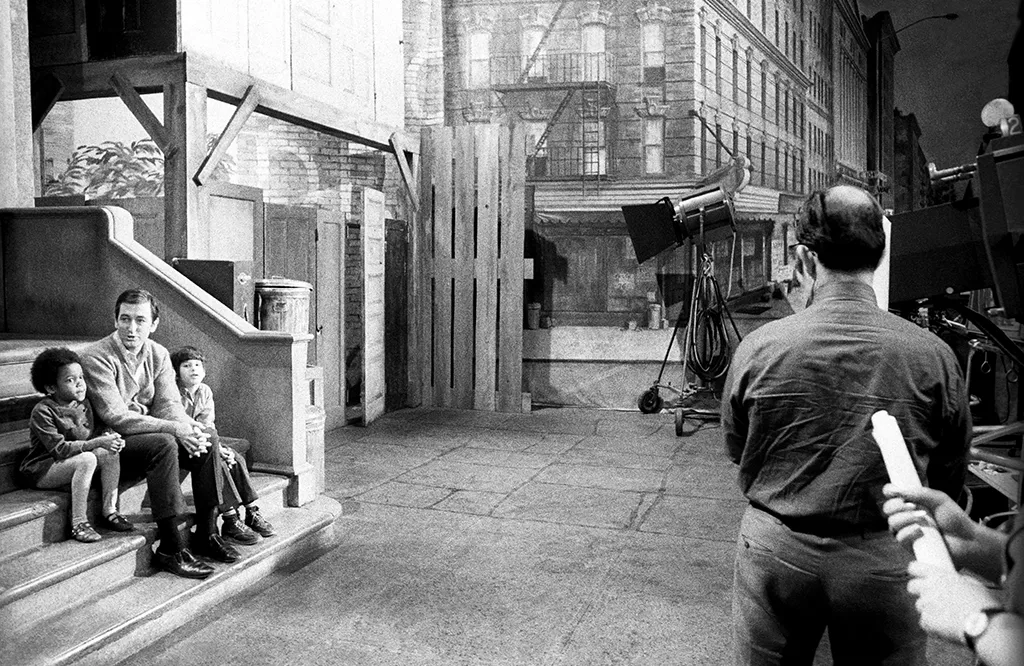

Since the 1950s, Ford has recognized that a healthy democracy requires a robust information ecosystem. We seeded NPR and PBS to democratize information, ensuring a farmer in Iowa had the same access to high-quality news and culture as a banker in New York. While the landscape has shifted today, our mission remains the same: to build the civic roads that lead people back to health, work, and agency.

“We seeded NPR and PBS to democratize information, ensuring a farmer in Iowa had the same access to high-quality news and culture as a banker in New York.”

Today, this infrastructure of trust is reinforced by the voices that document it. Through our grantee Military Veterans in Journalism, we support the placement of veteran fellows in high-impact regional newsrooms, such as The Kansas City Star, to ensure local reporting is grounded in the knowledge and cultural competency of those who have served. This initiative also equips newsrooms to dismantle regional stereotypes, replacing them with nuanced reporting that reflects the lived experiences of Heartland communities.

Similarly, the Butte America Foundation operates the radio station KBMF-LP as a vital node in the information ecosystem. For over a decade, this nonprofit community broadcaster has bridged the gap between rural Montana residents and decisionmakers through public interest programming and Indigenous storytelling. Whether airing local oral histories or connecting Tribal leaders directly with listeners, KBMF exemplifies how local media builds understanding and civic health.

In many rural Heartland communities lacking reliable broadband, public radio serves as a vital lifeline, particularly for emergency alerts during storms, fires, and power outages. The Public Media Bridge Fund was established to support under-resourced rural stations facing closure, ensuring they can maintain operations and continue providing these essential safety services.

Beyond information, we also support the architecture necessary to dismantle cycles of isolation and addiction. We fund groups like Vital Strategies to help Kentucky officials streamline naloxone distribution to reverse opioid overdoses and deploy mobile harm reduction units, fostering the trust between government and community partners necessary for repair and resilience. We also support VOCAL-Kentucky, which mobilizes across 120 counties to ensure community voices direct how opioid settlement funds are spent. Simultaneously, the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky works with regional partners on Project Renew, an innovative reentry program that pairs legal aid with recovery support. The program connects communities with essential services including housing, transportation, and treatment, as well as provides legal support to minimize barriers to reentry success.

By strengthening these diverse pathways, from rural airwaves to mobile health clinics, we are fortifying the very connections that hold a fractured society together. An investment in civic architecture is, ultimately, an investment in the infrastructure of belonging.

Democratic Wealth-Building

We have always believed that building stakeholders is what builds true prosperity. If the people living in a community don’t have a share in its success, growth remains fragile. We call this democratic wealth-building: a commitment to ensuring capital and ownership stay rooted where they are generated.

This vision began in 1979 when we provided seed funding for the Local Initiatives Support Corporation to help underinvested local areas access the capital and technical support needed to build opportunity and resilience. That work continued through a modest early grant to the First Nations Development Institute, which sparked a partnership that helped the organization evolve into a major intermediary for Indigenous communities. This investment led directly to the establishment of Community Development Financial Institutions across Native lands. This long-term support has empowered the First Nations Development Institute to strengthen Tribal economic sovereignty and expand financial resources within Indigenous nations.

“We have always believed that building stakeholders is what builds true prosperity.”

Today, this commitment to democratic wealth-building has evolved to champion employee ownership structures. We help workers build equity while keeping companies anchored in their communities. In Iowa, where many business owners are nearing retirement, our partnership with the Iowa Center for Employee Ownership at the University of Northern Iowa helps transition these companies to their employees. Because a local business circulates three times more money within its community than an outside firm, this model ensures economic vitality remains where it belongs.

We also bridge the opportunity gap for overlooked innovators by bringing capital and visibility to the Heartland. Through a significant partnership with the REDF Impact Investing Fund, we are training students from Marshall University, West Virginia University, and Ohio University to become the next generation of Appalachian investors. Simultaneously, we have supported the Idea Accelerator program run by Builders + Backers in partnership with Heartland Forward, supporting small businesses and emerging entrepreneurs as they scale sustainable local economic growth. These are more than business investments; they are investments in the local leaders who will shape their region’s future.

In Missouri, the Starkloff Disability Institute (SDI) is helping disabled people build wealth by fixing outdated Medicaid rules. Currently, strict income and asset limits mean disabled people often lose their vital health coverage if they earn or save more than a small amount. This forces many into a poverty trap where they cannot afford to work or save for the future. SDI is working to change these rules so health care supports employment instead of blocking, ensuring disabled Missourians can thrive and achieve financial independence.

What drives this work is not any individual effort, but a collective investment in the resilience of the American Heartland. As we look across the region today, we see communities reinventing themselves once again, from the revitalized corridors of Detroit to the innovation hubs of the Midwest. But for that innovation to last, it must be inclusive. It must be rooted in the stewardship of institutions, the strength of civic architecture, and the democratization of wealth.

From the Detroit of 1936 to the Heartland of 2026, our purpose remains unchanged. We believe that when you strengthen the bedrock, build the bridges, and give people a stake in their own destiny, the entire country rises.